By all accounts this essay was a kind of manifesto for the Russian painters and was a particularly significant influence on its leaders, such as Ilya Repin, Ivan Shishkin and Kramskoy. It explains why realism flourished longer there than it did in Western Europe.

|

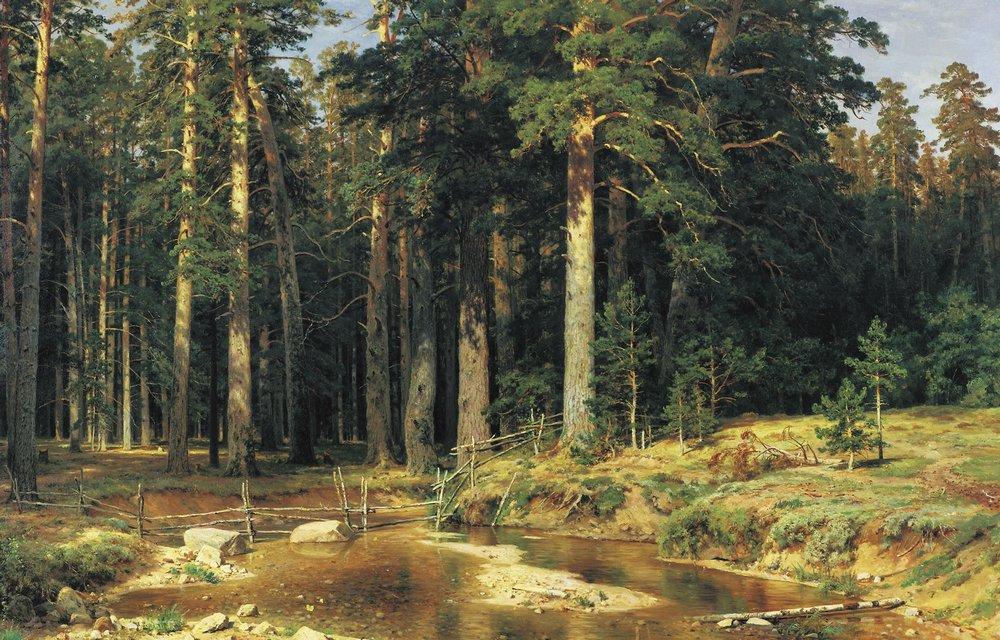

| Ivan Shishkin, Mast Tree Grove, 1898 |

For example, compare this painting by Shishkin in Russia in 1898....

|

| Paul Cezanne, The Bathers, 1898-1905 |

...to this one by Paul Cezanne in France at the same time. What was different about the aesthetic philosophy in Russia?

The central notion of Chernyshevsky's essay is that reality is greater than art. At best, art is an attempt to replicate or reproduce reality, and therefore art is on a plane lower than reality.

This is a very different idea from the aestheticism of J.M.W. Whistler and others who suggested that it is the business of art to improve on nature. Whistler said, "Nature is very rarely right, to such an extent, even that it might almost be said that Nature is usually wrong."

This is a very different idea from the aestheticism of J.M.W. Whistler and others who suggested that it is the business of art to improve on nature. Whistler said, "Nature is very rarely right, to such an extent, even that it might almost be said that Nature is usually wrong."

Around the same time that Chernyshevsky's influential essay was published in Russia, related ideas were published in England and America. John Ruskin's Modern Painters and Asher B. Durand's Letters on Landscape Painting (1855) preached a version of Truth to Nature that had a great influence on the movements Pre-Raphaelitism and the Hudson River School in English speaking countries. The main difference with Chernyshevsky is that he seems to lack the moralizing tone of Durand and Ruskin.

All these thinkers advocated that the artist should have a reverence for the concrete facts of reality and to allow as much as possible for the painting to be a clear window to that reality. Repin's portrait of Pisemsky is a good example, where the technique is subordinated to the force of personality, made manifest in concrete facts.

Ruskin, Durand, and Chernyshevsky all advocated that artists—students especially— paint as faithfully from nature as possible, but since absolute leaf-for-leaf imitation of external details is impossible, artists should re-create (Durand used the word "represent") on canvas the truth they have experienced, penetrating to the Platonic essence.

In Shishkin's case this meant painting scenes that seemed "found" or "photographic" to the untrained eye, but were in fact carefully constructed using his deep knowledge of natural effects.

It took him a lifetime to discard the conventional formulas of the picturesque in landscape, and to invent a way to interpret the reality of a forest interior in oil paint.

Many contemporary realists place a great value on the aesthetics of brushwork, paint texture, and composition, but Chernyshevsky would have regarded this preoccupation as a foolish distraction, like focusing on the scratches and skips on a phonograph record instead of listening to the music. Just as a phonograph record aspires to deliver the experience of a live concert, a painting aspires to the fullness and presence of reality. (The concert/phonograph analogy is my own, and of course the phonograph came after his time; Chernyshevsky actually uses the analogy of an original painting versus an engraved reproduction of it).

|

| Ilya Repin, Portrait of Aleksei Pisemsky. 1880 |

Ruskin, Durand, and Chernyshevsky all advocated that artists—students especially— paint as faithfully from nature as possible, but since absolute leaf-for-leaf imitation of external details is impossible, artists should re-create (Durand used the word "represent") on canvas the truth they have experienced, penetrating to the Platonic essence.

In Shishkin's case this meant painting scenes that seemed "found" or "photographic" to the untrained eye, but were in fact carefully constructed using his deep knowledge of natural effects.

It took him a lifetime to discard the conventional formulas of the picturesque in landscape, and to invent a way to interpret the reality of a forest interior in oil paint.

Many contemporary realists place a great value on the aesthetics of brushwork, paint texture, and composition, but Chernyshevsky would have regarded this preoccupation as a foolish distraction, like focusing on the scratches and skips on a phonograph record instead of listening to the music. Just as a phonograph record aspires to deliver the experience of a live concert, a painting aspires to the fullness and presence of reality. (The concert/phonograph analogy is my own, and of course the phonograph came after his time; Chernyshevsky actually uses the analogy of an original painting versus an engraved reproduction of it).

Here are some excerpts of Chernyshevsky:

- A reproduction must as far as possible preserve the essence of the thing reproduced; therefore, a work of art must contain as little of the abstract as possible.

- Art expresses an idea not through abstract concepts, but through a living, individual fact.

- The essential purpose of art is to reproduce what is of interest to man in real life.

- Reality stands higher than dreams.

Me: Can a camera or a high resolution motion picture achieve this result?

Cherny: No. The excitement that the human being experiences in the presence of reality can only be evoked by an artist with an inquiring mind who can imaginatively see into the structure and essential features of the subject, and express what it is about that subject that makes it interesting.Me: Is the imitation of reality what we're after?

Cherny: No, the mere copying of external features will only lead to boredom, both for the artist and the viewer. There's a big difference between mindless copying and insightful reproduction of nature.

Me: Aren't such insights highly subjective? Science in recent decades has shown that there is no such thing as objective reality. Our perception of the world around us is a construct of our perceptual systems. Therefore, shouldn't we paint the world in a personal style that matches our own subjective view of the world?

Cherny: You make too much of that. Painting in the way you suggest is just an excuse for laziness. Two careful artists with good training will produce studies that match each other very closely. But such studies are just the beginning. It takes a lifetime to create works that address the deep experiences of life.

Me: What about the Surrealist's goal of painting what is inside the mind, the world of dreams and nightmares?

Cherny: Your dreams ultimately come from reality. Imagination plays a key role, but the aim of the artist is to use the imagination to see into the heart of reality itself, which is the source of everything in its fullest and purest form. Reality is also full of latent mystery that cannot be fully understood by either the poetic avenue of art or the fact-based avenue of science.

Me: If reality is greater than art, of what value is a visit to the art museum?

Cherny: If it's a choice between the two, artists should look to reality for their chief inspiration; otherwise their work will become second-hand and mannered. But it is extremely valuable to study the means by which great artists of the past have expressed the essence of reality. Look for artwork that brings you closest to the feeling that you are in the presence of real life, and then try to understand how those effects are achieved. The challenge when you leave the art museum is to leave behind the conventions of past art movements, and to see reality for yourself without preconceptions.

Me: What categories of art are most worthy—sublime, comic, tragic, or beautiful?

Cherny: They are all important. A sensitive person will respond to the problems presented by life, and will want to create art that speaks to those problems, so that a fellow human can gain wisdom and insight from the art. Those impulses can run the gamut of emotions. Whatever way you respond to nature should be the subject of your art, but it should be conveyed in concrete, material terms.

My concluding thoughts: I don't think Chernyshevsky's idea is completely tenable intellectually for me. I can't get past the idea that "reality" is a provisional thing, constructed in our own minds, and subject to the whims of our very selective and subjective visual systems. I also resist the notion that abstraction must always be avoided. Of course I love the Russian realists, but I also feel that a pulsing sense of life can emerge from certain highly abstracted forms of art, such as hand-drawn animation or comic art.

But Cherny's idea that reality stands on a plane above art is for me an extremely useful driving concept that helps focus my mind when I'm out painting from nature. I often achieve my best results when I try to capture what's in front of me without trying to "improve" on it in any way. When I compare the immense complexity, subtlety, and richness of the real world to my own paltry efforts, I'm left with a sense of how far I have fallen short of the truth in front of me.

-----

"The Aesthetic Relations of Art to Reality" by Nicolas Chernyshevsky.

Nicolas Chernyshevsky on Wikipedia

Recommended book: The Russian Vision: The Art of Ilya Repin by David Jackson

by David Jackson

-----

"The Aesthetic Relations of Art to Reality" by Nicolas Chernyshevsky.

Nicolas Chernyshevsky on Wikipedia

Recommended book: The Russian Vision: The Art of Ilya Repin

I think there's a lot of truth in the idea that the way we perceive reality is more engaging than any attempt to interpret reality through art. However I think Cherny's philosophy is leaving out imaginative work. Ilya Repin may have been held back by his cultures focus on strict realism. Some of his earlier paintings were great scenes from fiction or from history, and he stopped doing those.

ReplyDeleteYou are right that reality is what our senses interpret it to be. Because reality is in our mind, omitting things which only exist in our mind is denying part of the human experience.

Artwork provides a window into how the artist sees the world. Even when two artists trained the exact same way copy the same Bargue and both are equally dedicated to reproducing the original exactly, they don't turn out the same at all. There's nothing wrong with aspiring to depict nature exactly as you see it, but that's not the only reason art is good.

There are so many different philosophies in the art world. It's interesting and makes me wonder how the time period and cultural context may have played an influential role in the minds of these artists. Chernyshevsky's musical metaphor was interesting likening brushwork, composition, texture to scratches on a record as distractions. As a visual artist who is very influenced by music i feel the expressive work found in impressionism, comic art, and many others is personally much more evocative like music can be. A composer is making so many different choices about arrangements, instruments, composition. However i can imagine Chernyshevsky's philosophy being very useful for certain subject matter and artistic goals, like when the goal is to engage the world and your surroundings with total honestly...i could see these aesthetics working well with artistic activism. The more I read about different styles of art the more options i feel there are when considering how to go about painting a subject. Depending on what your trying to convey one approach or a combination of them might communicate the best.

ReplyDeleteYour description of Shishkin's painting approach, "...carefully constructed using his deep knowledge of natural effects...", is so profound in terms of what influences an artist's choices during a painting. That "deep knowledge" is a lifelong pursuit in itself, and as it develops, the quality of the art will follow.

ReplyDeleteI also agree with Chernyshevsky's statement, "The essential purpose of art is to reproduce what is of interest to man in real life", and believe that is where an artist's individuality will show through, even if the techniques are the same as others'.

One of your best posts, James. Actually prompted me to "say it".

Thank you,

Bill

As someone who is primarily a naturalist wildlife artist who sees a lot of animal art in one place or another, this in particular seems quite relevant to that genre...."the mere copying of external features will only lead to boredom, both for the artist and the viewer. There's a big difference between mindless copying and insightful reproduction of nature."

ReplyDeleteI agree that it's a matter of subjectivity. Really, it's a matter of the viewer themselves. Some people will love realism, some people may always prefer something more abstract and fantasy-based.

ReplyDeleteIn that regard, I don't agree with Chernyshevsky's "reality is above art" line. People get bored with things over time, and want something more, or simply want to escape reality. It's exactly why people dream and create fantasies, try new things like Picasso did, etc. It's the reason why I enjoy your paintings and others of such similar nature: they are realistic, but with an added sense of character that can only be seen through a painting. Nature can't reproduce that.

I also like the comparison you made between the Shishkin's forest and those bathers: not my favorite Cezanne, but still fascinating. Both paintings were done "at the same time", in 1898, but Cezannes labour lasted from 1898 - 1905, it says here, and still it hardly looks finished, whereas Shishkin's accomplishment probably didn't take him more than a year.

ReplyDeleteA late work by Cezanne, these bathers, and still he went on struggling, seven years , in search of a deeper reality and unity.

He may have failed on this one, but still...there's something captivating each time I look at it.

What both paintings have in common, Cezanne's and Shishkin's: both of them don't "hold up the mirror to Nature", they are neither a copy, nor photograph, nor a mere shadow. Both have been envisioned by some inner eye, I would say.

I think you are giving Chernyshevsky too much credit, when you have him admit that "There's a big difference between mindless copying and insightful reproduction of nature." I don't believe he actually saw art as anything but mindless copying - his assertion that art is by definition inferior to nature is very suggestive of that. But not just that; Chernyshevsky's chief hangup had been on asceticism, naive scientism and austerity.

ReplyDeleteHe was a prolific publicist and writer; but even his prose was mostly a vehicle for his philosophy. He was an early socialist, and his chief maxim had been decent life for all people, but his view of that decent life had been rather totalitarian in vein of Plato or Campanella. Utter collectivism, austerity, pragmatism, rejection of anything beyond necessities. A major character of his longest book, the "man of the future", is engaged in ascetic practices like sleeping on a bed of nails, and refuses to eat apricots because the average provincial peasant has no access to them. Chernyshevsky's writing style is virtually the same in novels and newspaper articles; the man had been a hugely influential political activist, but apparently quite aesthetically blind.

The demand that art, where it is allowed to exist, can only aspire to imitate reality, is entirely in vein of his ascetic views and aesthetic blindness. I don't believe he would even make the finer difference between photographic-like imitation and insight. I am not sure he would even notice any insight. He made everything in his life subservient to fighting for his socialist ideal.

The difference between art traditions in Russia and France at the time can be explained by simpler things. For instance, the progressive Russian artists had rejected the stale subculture of the Academy, but did not throw out the whole Academical painting skill set with that, making a banner out of that rejection like the Impressionists did.

They painted peasants and soldiers instead of biblical themes and Greek myth, in the same high-quality Academical style. They did not really notice the Impressionists, but instead had a different kind of rebellion in the vein of Courbet's Realist movement. The fight had been about subject matter and relevance of art subjects for modern life, not about painting styles.

When Impressionism got more mainstream and finally got noticed in Russia, its ideas and techniques were quietly incorporated in the academical skill set instead of replacing it. The Impressionist-like rejection of the academical painting happened much later, in 1920s, in form of what is now known as Russian Avant-garde, and dealt with it much more radically than the Impressionists ever dared.

Eugene, thanks for all those thoughtful points, particularly about how the painting approaches played out in Russia compared to France. Great insights.

ReplyDeleteI can't agree that the Russian painters "did not really notice the Impressionists." Repin and others spent time in Paris soaking it all up, and while he didn't agree with all of it, he did recognize and adopt many of the ideas about color and light and painting. People like Repin and Levitan definitely absorbed the best ideas that Impressionism (and in the case of Shishkin particularly, the Dusseldorf School) had to offer without losing their academic chops, as did people like Zorn, Sargent, and Sorolla.

I haven't read Chernyshevsky's other writings, but I'm aware that they're very political. I'm basing the post on the text of this essay itself, which I would argue does draw an overt distinction between mindless copying of external facts and a more insightful interpretation. The importance that the essay played in Russian art history comes mostly of my reading of David Jackson's excellent histories of Russian painting. Obviously Chernyshevsky was just one of many voices that the artists were listening to. The critic Stasov was also extremely influential on Repin, convincing him to focus more on real life and less on history and fantasy.

In the text Chernyshevsky says not only that mindless imitation is impossible, but he also kind of anticipates the "Uncanny Valley" phenomenon: "Since it is impossible to achieve complete success in imitating nature, all that remains is to take smug pleasure in the relative success of this hocus-pocus; but the more the copy bears an external resemblance to the original, the colder this pleasure becomes, and it even grows into satiety or revulsion. There are portraits which, as the saying goes, are awfully like the originals."

..."there are Portraits which, as the saying goes, are awfully like the originals."

ReplyDeleteha ha ha...good point, or as the Germans would say: "Gute Pointe"

:')

Excellent essay, and I loved your speculative interview!

ReplyDeleteOne would notice these things too, even among the photographers. The best photographers in the past were ones who added the magic, and today, with image post processing and more photographers choose to enhance the reality into a different kind of hyperrealism, often bordering on surrealité.

ReplyDeleteI actually did my BFA printmaking thesis based on this essay: I thought it would be amusing to distribute communist propaganda to the entire school and push against the faculty's more conceptual art leanings in a way that most of them wouldn't realize how radical I was being since I suspected none of them would go to the source material. I felt that there was no place for the professors to be teaching concept when they were, in my eyes, failing to teach the basics rigorously enough. Chernyshevsky's essay really appealed to me as a good higher authority to point to, but I tried to present my version with a less confrontational anti art for art's sake thesis that seemed to appeal to most who read it.

ReplyDeleteThis is what it looked like, if you are interested (the essay is legible in the full resolution of the images): http://wiwaffles.tumblr.com/post/41155884621/the-human-frame-my-bfa-thesis-exhibition-i

Wonderful post, and very enlightening. I struggle with the idea of making reality more than it is, especially when I'm at a point in my artistic learning where accurate rendering is difficult enough. I wonder if faithful rendering will ever become easy or if one has to constantly juggle accurate rendering with the conceptual.

ReplyDeleteRegardless, your post is insightful, well written and inspires me to be a better writer on my own blog.

Thank you for your insights - this is a terrific post and I have learnt a lot. I knew almost nothing about Russian painters and have been shocked to discover in my various books (misleadingly called things like "Art-The Whole Story") that there are no reproductions and no words about this amazing group of painters. I am so happy to have been introduced to them. We have forests here in Devon that look exactly like the Shishkin painting on your blog, it is quite spooky how he has captured what is their very essence some how.

ReplyDeleteThank you, James.

ReplyDeleteI should have said that they didn't flock to Impressionism, rather than that they had not noticed it. The Russian artists clearly appreciated the novel approach, but apparently did not see the need to throw away the old ones that worked. The result was a synthesis, instead of a revolution - you correctly point out other examples of such synthesis in Zorn and Sorolla. Russian art of the last quarter of the 19th century is full of such synthesis - from very loose, impressionistic in the narrow sense of the term, painting of Serov and Korovin, to subtle information of the mostly academical painting of Repin.

I had looked through the text you linked to. I am not sure where it comes from; there are three available works published under this title in Russian, but neither of the two shorter ones matches the text. I presume that the English text contains excerpts from the third one, his dissertation on the topic. But on to the text.

It seems to me that Chernyshevsky argues against aesthetics in general: he dismisses art itself as inferior to reality, attempts to reproduce reality with precision as pointless, and attempts to use technique to create an illusion of reality as despicable trickery. In the beginning, he views art as a poor man's sightseeing: if you cannot travel to the sea, you have to settle for looking at lowly pictures. He switches the definition of beauty, claiming that the most beautiful thing in human life (love, according to him) cannot compare to the magnitude of beauty in nature, and therefore poetry must focus on descriptions of nature, not on love. Then he bashes poetry and literature for focusing on emotion instead of discussing important things, presumably philosophical or political; he even writes: "[the thinking man's] works will be, as it were, essays on subjects presented by life.[...]In such a case the artist becomes a thinker, and works of art, while remaining in the sphere of art, acquire scientific significance." He criticizes Goethe for using a fantastical plot instead of finding similar situations in real life. And so on.

So what is the purpose of art, according to Chernyshevsky? First, it is "to reproduce phenomena of real life that are of interest to man." Second, "to explain life" - meaning, to educate in a more entertaining form than a "dry reference". Third, since the artist cannot escape judging the phenomena of life, which judgment will color any artwork he produces, art has a moral purpose. Any kind of beauty, emotional element, etc. do not enter the picture. According to Chernyshevsky, art is good when it is utilitarian. Get rid of all fantasy, but don't copy reality either, he tells the artist; the answer, according to him, is becoming a philosopher and using art to influence and educate. Then the imperfection of art can be forgiven, because it shall serve the purpose.

It is quite in line with his own writing, certainly.

In his coy self-review of his own dissertation, he argues that there are "real" human needs and "idle" ones, and calls for reform of aesthetics, claiming that there is an absolute criterion of beauty in nature, therefore the human art must serve that criterion. The criterion is, again, utilitarian: according to him, beautiful things are what we like; tragedy is bad things happening; again, he ignores the form or emotion, and conflates art with actual experiences, and concludes that art is only worthwhile when it is a "teaching aid".

[cont'd]

[cont'd]

ReplyDeleteI suppose it is fortunate that the contemporaries took all that as a call for more realism in art. Because it seems more likely that he was arguing for abolishing art as art, and keeping only art as a vehicle for education/propaganda and a substitute for first-hand experiences.

Incidentally, while researching his works, I stumbled on a rather disjointed essay attacking the theory of evolution on the grounds of a claim that it means that "bad things are actually good" and therefore illogical. He proceeds to bash Darwin for being too thorough with facts, lecturing the English scientist on the pointlessness of collecting data - it would have been much better, according to Chernyshevsky, just to ignore missing facts, glossing them over with a phrase like "I believe it is so, and going into detail would be out of scope of this work". He ridicules Darwin for doing tests on whether branches with fruit could survive floating over to an island, because "it is clear that most islands with land species had been parts of continent once, and the minor exceptions are not that important". Then he criticizes the natural selection again, saying that bad things happening to individuals end with individuals - completely missing the point. In the end, he cannot argue with geology and the tree of life, but still says that the development of complex life was due to some vague "multiple forces that increase organizational complexity against the direction of natural selection". For the guy who was so bent on rationality and scientism, this anti-science obtuseness can seem surprising.

But if you look at his other favorite points - austere utilitarianism, anti-aestheticism, belief in absolute cultural criterion - it is quite in line with his underlying totalitarian Platonism. It is easy to think he was a progressive force; and for his time he was, but his progress is in the direction of North Korea.

Eugene, thanks for looking deeper into his other writings. I guess it's one thing for me to look at the essay at face value and see if it has anything to offer me. What his writings meant precisely to each of the Russian painters, and what it meant in the context of his political philosophy is far beyond me, but I'm glad you could share more insights about it.

ReplyDeleteRegarding the question: what is the purpose of art? Tolstoy is pretty clear in his definition of art that the purpose of art is for the artist to transmit a truly felt emotion to a fellow human, and so express feelings of brotherhood. In the way he talks about it, that's a pretty universal purpose that stands above any particular political philosophies or lifestyles. But Tolstoy, and perhaps Chernyshevsky and Stasov and other Russian intellectuals at the time (from the limited amount I've been able to glean), seemed just as you say to be against the highly artificial creations like grand opera. (I kind of disagree with that, by the way, and I really love opera.)

Asher Durand's writings talk about the purpose of a painting being kind of a window to another world that can bring pleasure to another man at the end of his (or her) workday. The painting brings the viewer back to memories of childhood. Durand beautifully expresses the joys of picture gazing, mixed with a reverence for the divine quality of nature, like going to church, but in the sanctuary of Nature.

So anyway, there are many avenues to art, and many justifications for realism, and I like trying to understand the driving ideas to see if there's anything I can use from them.

Jim, an obviously very influential post, very applicable to my own work and viewpoint. Thank you so much for your academic approach to creation. While I will likely never read the source material I am deeply informed by your digests.

ReplyDeleteInteresting post and comments.

ReplyDeleteEventually we all have our own ideas, realism or not. Myself I find hyper-realism just for the sake of realism, boring. But using experience in realism to go beyond it as you do is what I consider to be art.

In my own work I am less interested by realism and more drawn towards simplicity, that's in fact really hard as it has to be based on observation too.

But in a museum or gallery I might be drawn to anything as long as it's really creative no matter what style.

I enjoyed this post very much. There is beauty in all art, however, the art expressed from a strong appreciation of reality seems to reach braver heights, including abstract art in my opinion. Your imagining a conversation with Cherny was itself an abstraction based on reality (the essays, paintings, and works of Cherny and his students). Perhaps that's what made this article all the more magical :)

ReplyDeleteOf course I've seen that you've been using Chernyshevsky's essay as a wall to arrange your own thoughts, James. There's much more Gurney in your imaginary dialog than Chernyshevsky, but that's completely fine with me. :)

ReplyDeleteI've been reading a completely unrelated biography, had to look up a reference, and accidentally found out that there was a precursor to Chernyshevsky's particular brand of socialism: Charles Fourier. His utopia as he described it is a spit image of Fourier's "phalanstère", which Fourierists had even attempted to create, but which had always failed rapidly. Not an exact reproduction of Plato's Republic, but idealistic socialism in the same vein, with addition sexual liberty and monetary incentive. So I suppose I should retract the North Korea accusation - Chernyshevsky had hardly envisioned such an end result - but the rest holds.

As for the purpose of art... I cannot help noticing that everyone you cited had a favorite agenda to push, using art as means to it. :) Chernyshevsky wanted art to educate, Tolstoy wanted art to lead to brotherhood of men, Durand wanted it to please and awe, Stasov wanted it to nurture national identity. I am wondering what Gurney wants it to do!

The best definition of art I can make is this: art is a mode of communication which includes a second message with subliminal emotional content, along with the primary "surface" message. A text may inform, a work of literature informs in a way which makes the reader feel things. A drawing may depict something, an artistic painting depicts something in a way that makes the viewer feel things. And so on. This is as agenda-free, and as universal, as I can make it, while still being useful for telling good art from poor art.

And any purpose beyond communicating is up to the artist. :)

Eugene, thanks for these fascinating questions and comments. I've been thinking about all your comments as I've been reading Dmitri Sarabianov's book on Russian Art, and they seem to bear out a lot of points you've been making, particularly the connection between aesthetics and politics. In the case of Chernyshevsky, one of his novels about communal living encouraged a group of artists to live collectively, and even share in the commission income. It was an experiment that didn't work out very successfully. Another point was that with the societal ills of Russia in the mid-19th century, there was no democracy or other outlet for political expression except literature and painting. That gave painting a particularly important role to be the voice expressing feelings of the people, maybe a bit like folk music in the US in the 1960s.

ReplyDeleteAs for my own personal agenda, I'm not conscious of one, and certainly am not trying to get across any hidden message in my work—I just delight in the ability of painting to capture and transmit my experience and feeling to others, and in the power of stories to bring us in contact with other people and other worlds.

I think the agenda-driven philosophers who have historically promoted realism fascinate me perhaps because their zeal has the effect of pushing us artists (whatever our politics or philosophies might be) past our usual torpor and willingness to compromise, and to produce our best work. I like your definition, which as I understand it is not only agenda free, but it leaves the mechanism by which art transmits that emotion to be mysterious.

I am enjoying this exchange too, James. Even if I am slow to reply. :)

ReplyDeleteYes, Russian public politics had been next to nonexistent for most of the second half of the nineteenth century, and the only place where any kind of public discussion took place was literature. (Which somewhat explains the blooming of Russian literature in that period.) Painting was less important compared to that, although it did sometimes deal with contemporary issues and discussed. I know of only one case of a painting which was a direct (and rather acerbic) response to another painting, and that one wasn't political. But you can make a lot of Aesopian statements through seemingly innocuous paintings, in context!

As for agendas, an artist doesn't necessarily need one. The "second" message in most cases isn't even a conscious one, it's just the artist's personality and mood affecting the picture. It is inevitable that they will affect it. An artist could have an agenda, and try to instill a specific emotional message, but success will depend on whether he really feels strongly for it. If not, the result can range from pedestrian to revolting! The true personality and feelings of the artist will shine through, and can contradict the superficial content, be it a story or an abstract composition. Case in point: compare any naive artist who loves his subject matter to, say, Lucien Freud who visibly hates his models.

So it's not important if the artist wants to instill a particular mood into the painting, or it just happens by itself. What is important that the artist's personality is good, because it will show through his works, and little could be done to mask it. :)

But I don't believe the mechanism is that mysterious. Common cultural context, normal human empathy, and the artist's betraying movement are quite enough to explain it.