|

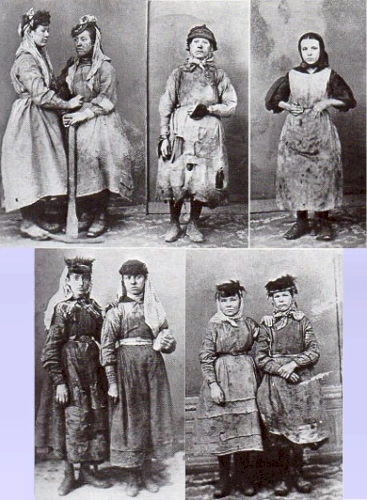

| Arthur Munby with Ellen Grounds, a "pit brow wench," 1873 |

The first thing that comes to my mind when one thinks of jobs for Victorian lower class women are domestic jobs: kitchen and washing and that sort of thing.

But Victorian women also worked in rough, dirty jobs outside the home that one would think were suitable only for men. For example, the so-called "pit brow wenches" worked at the top of coal mines to shovel the chunks of coal into waiting railroad trucks.

They wore trousers and would come home black with dirt. Other women worked inside the mines, crawling on their hands and knees, pulling mine carts with chains attached around their waists.

The work of these women might have been largely forgotten were it not for Arthur Munby, who had a fascination and an admiration for them. He convinced many of them to pose in photographic studios, as cameras in the 1860s couldn't function in the low-light conditions that prevailed at the worksites.

He also carefully documented them in interviews and notes, leaving behind a rich sociological record.

Munby even courted and eventually married a servant woman named Hannah Cullwick, but he had to keep the relationship secret from his family for 20 years.

The reality of life for Victorians is evident from the dirty and ragged appearance in Munby's photos. Here are some "tip girls" from Wales. Munby insisted on photographing these women "in their dirt."

Paintings of Victorian working women were rare, and tended to show a sanitized view with soft hands, a smile, and a bright white apron. In 1859 Munby had lunch with John Ruskin, telling him about his project, and suggesting that "some one ought to paint peasant girls and servant maids as they are —coarse and hearty and homely — and so shame the false whitehanded wenches of modern art." But nothing came of it.

Some of the strangest trades for women could be found in the dark alleys of London that upper-class people rarely saw up close, much less photographed. James Greenwood reported in his book Low-Life Deeps:

"Strange trades are carried on in these slums, and occupations are followed which in civilised parts are never dreamt of:, except it be in exceptionally bad dreams.... There is an awful little alley, for instance, in the neighbourhood of Hales's tallow factory, consisting of about twenty houses, inhabited almost entirely by folk who collect the ordure of dogs, which is used for tanning purposes."

"There are but few left there now, I am informed, but not very long since the residents of this delectable spot consisted chiefly of "cat-flayers" - whose sole means of living was to go out at night with their sacks and sticks, hunting for cats to be slaughtered for the sake of their skins...It is unfortunate... that to be saleable the hide must be taken from the body of the animal while it is in existence, and still more so that the villainous cat-flayers are not deterred by this difficulty. I was further informed that the neighbourhood used to be scandalised by the presence of the flayed carcasses of poor grimalkins lying about, but that now that indecency is avoided by an economical arrangement on the part of the flayer. He now puts his dead cats in the copper, and makes further capital of their bones and fat."

Above quote from Victorian London.

Book: Victorian working women: Portraits from life

Arthur Munby and Hannah Cullwick on Wikipedia

Jim, your post today reminds me of the opening passage in Steven Johnson’s book titled “The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World” (2006):

ReplyDelete“It is August 1854, and London is a city of scavengers. Just the names alone read now like some kind of exotic zoological catalogue: bone-pickers, rag- gatherers, pure-finders, dredgermen, mud-larks, sewer-hunters, dustmen, night-soil men, bunters, toshers, shoremen. These were the London underclasses, at least a hundred thousand strong. So immense were their numbers that had the scavengers broken off and formed their own city, it would have been the fifth-largest in all of England.”

Thanks for that colorful passage, which almost makes me need to take out the deodorizer. I was amazed to read recently that ordinary garbage collection (cans put on the street for garbagemen to pick up) didn't exist before World War I in most American and European cities. It wasn't just horse manure that the street sweepers were cleaning up -- it was everything.

ReplyDeleteThey also worked in textile mills. There is a excellent drama from the British channel 4 called The Mill about the young women and children who worked the mills in the mid 19th century.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cbIC0sVnRbU

Did anyone else have to look up the term "Grimalkin"? Thought for a second it was something from Harry Potter books!

ReplyDeleteHadn't known this that close:

ReplyDeleteNice bit of history.

Here's a fanciful take on some of those occupations, in comedic form. I think the Thenardiers in Les Miserables would have been the revolutionary era french equivalent. It seems poverty is an enduring part of the human condition.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.amazon.com/The-World-Poo-Terry-Pratchett/dp/0857521217

Nice bit of history, I wrote: errhh...

ReplyDelete...should have read, in today's nomenclature:

"Nice byte of history"

:´)