RISD student Kelly Berg said that one of the favorite parts of her job as monitor in the Nature Lab of

Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island is handling the Madagascar hissing cockroaches. “The make great pets,” she told me. "They hiss a bit, but they’re quite friendly."

The lab’s collection gives art students access to living animal specimens to use as models. Besides the giant cockroaches, there are millipedes, rhinoceros chameleons, rats, frogs and turtles.

There’s also a large variety of animal skulls and skeletons. One room adjoining the nature lab collection had half a dozen human skeletons with drawing easels set up beside them.

Along the walls were cabinets crammed full of shells, seedpods, and crystals.

This student from nearby Brown University, one of the Ivy League colleges, was doing a careful pencil drawing of a stuffed squirrel. Brown students can share in RISD’s art offerings. In exchange, RISD students can broaden their education by enrolling in Brown’s first-rate courses in academic subjects to supplement the focused art curriculum.

RISD students also have access to the collection of the

RISD art museum, whose collection ranks with some of the finest small museum collections of the northeast.

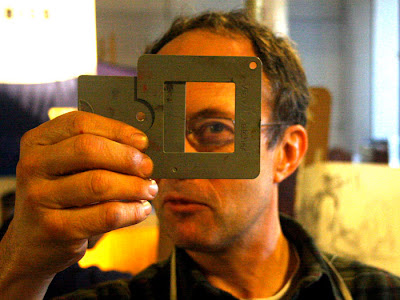

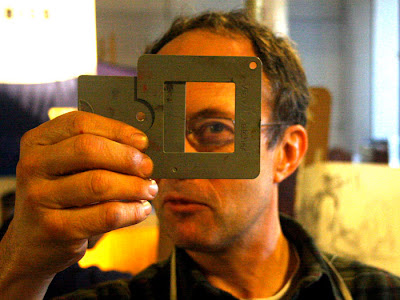

Illustration chairman

Nick Jainschigg (above) toured me through the building which houses classes for the approximately 250 illustration majors. The school has graduated some notable illustrators like Chris Van Allsburg and has attracted some current high-profile teaching talent, including Jon Foster. Classes keep current with emerging trends, and include offerings in graphic novels, 3-D character animation, and video game design.

We met painting instructor Nick Palermo, here demonstrating a “View Catcher” device, which helps new painting students frame a composition. Palermo’s class was working on oil studies of a model posing on a stand with colorful props and upshot lighting.

Part of what makes RISD’s program unique is the winter session, sandwiched between the regular semesters. The six week winter session is both informal and intensive, allowing students to try out something outside their normal experience, like stone lithography or glassblowing.

The Fleet Library

The Fleet Library in the newly refurbished bank building contains not only a rich collection of art books dating back to the 1860s, but also a vast array of scrapbooks, sketchbooks, design collections, clippings, art prints and ephemera.

More than one person admitted that not enough RISD students take advantage of the school’s rich resources, and that the requirement to use them is not woven enough into the curriculum. But for a motivated student, RISD certainly has a lot to offer.

We checked and nothing seemed to be taken from the back of Trusty Rusty, but there was a little note on top of the load. It was kind of creepy—some crackpot stalker apparently trying to take credit for Dinotopia: Journey to Chandara.

We checked and nothing seemed to be taken from the back of Trusty Rusty, but there was a little note on top of the load. It was kind of creepy—some crackpot stalker apparently trying to take credit for Dinotopia: Journey to Chandara. I guess you can expect anything on Halloween, but how would this guy, whoever he is, know where we were at that moment?

I guess you can expect anything on Halloween, but how would this guy, whoever he is, know where we were at that moment?