Swedish painter

Anders Zorn (1860-1920) has long been associated with a limited palette of four colors. Rosemary Hoffman, in the book

Northern Light: Nordic Art at the Turn of the Century

wrote, “Zorn was noted for executing paintings using a sober color scale limited to white, ochre, vermilion, and ivory black.”

Hans Henrik Brummer, writing in the

1986 catalog on Zorn

, said “basically his register was limited to black, white, earth yellows and vermilion; other pigments could be used if local accents were needed.”

Several art teachers, such as

Jeff Watts, use the “Zorn palette” (sometimes substituting cadmium red light for vermilion) as a teaching tool because it provides students with a finite range of color choices with a wide enough gamut to handle most figure paintings. The gray can appear as a blue in the context of the limited palette.

But recently some authorities have cast doubt on Zorn’s use of the limited palette.

Bob Bahr of American Artist magazine states that the so-called Zorn palette “may be a very useful tool, but it is a mistake to attribute it to Anders Zorn.” Bahr cites Birgitta Sandström, the museum director of the Zorn Collections in Mora, Sweden, who claims that she has “difficulty even comprehending the assumption that Zorn worked with the specialized palette associated with him” because of the fact that blue and green are found in some of his paintings, and because those colors were found among his studio effects.

She reports that “17 tubes of cobalt alone are represented among the 243 tubes of paint left by Zorn in his studio in Mora.” Merit Laine, curator of prints and drawings at Stockholm's Nationalmuseum, “concurs that the notion of a Zorn palette is a bit of a misnomer.”

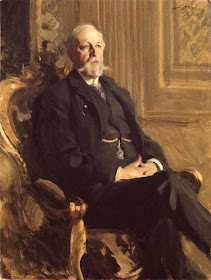

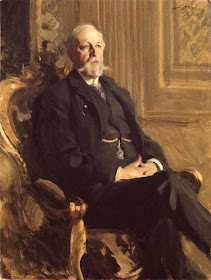

I don’t claim to be a Zorn expert, but speaking as a painter, I think these commentators are mistaken and have likely overstated the case. No one has suggested that Zorn exclusively used the ultra-limited palette. Obviously, many of his paintings (such as the one above) use a wider array of colors, including blue.

I believe there’s also a logical problem with the evidence of the surviving paint tubes. They don’t prove much. In my own case, the back of my paint drawer is crammed with dozens of colors. Some of them, such as Aubusson Green and Tuareg Blue, I purchased cheap and I never use; some I haven’t touched in 20 years. Some are so expensive I hesitate to use them. Some have caps or labels that fell off and I don’t know what they are. Some are so toxic that I avoid them like nuclear waste. Some are stuck to the bottom of the drawer in a pool of leaking linseed oil that turned to glue.

I often use limited palettes, but you would never guess it from looking in my paint drawer.

What evidence is there that Zorn used the famous four-color palette? First, many of his paintings appear to be painted within a narrow gamut that could have been painted from those colors.

Theoretically, one could paint such a picture from either a full palette or a limited palette. A chemical analysis would prove it for sure.

Many of Zorn’s heroes, such as Frans Hals, Diego Velasquez, and James M Whistler, used limited palettes. Talk about limited palettes among artists of Zorn’s day was commonplace.

There’s also the testimony of fellow painters writing about Zorn’s palette during Zorn’s lifetime. For example, European-trained

Birge Harrison (1854-1929), in his book “

Landscape Painting

” in 1909, says: “The expert cannot be bothered with useless pigments. He selects the few that are really essential and throws aside the rest as useless lumber. The distinguished Swedish artist, Zorn, uses but two colors—vermilion and yellow ochre; his two other pigments black and white, being the negation of color. With this palette, simple to the point of poverty, he nevertheless finds it possible to paint an immense variety of landscape and figure subjects.”

Then there are the actual palettes that survive in the Zorn museums. This one may have a touch of cadmium yellow, or perhaps a dab of blue or green, but it’s a small palette and a small box, and it seems to emphasize the main four colors.

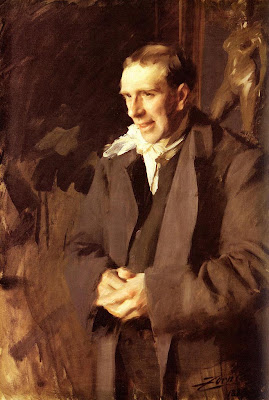

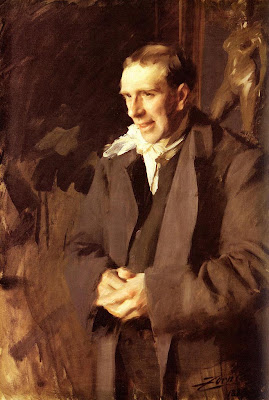

Finally, there is the self portrait, which clearly shows the palette with the four colors: white, ochre, red, and black. Zorn was conscious of his own image. He was aware that he was an artist’s artist even in his own day. He proudly showed off the four-color palette.

What the doubters need to understand is that a limited palette is not a sign of impoverishment, but rather of resourcefulness. As Brummer says, “limitation could, in fact, be an asset.” Zorn’s experiments with limited palettes were a part of his virtuosity, a token of his strength as a painter.

LINKS

"Sweden's Sargent" on the American Artist website.

Anders Zorn complete works (website)

Anders Zorn on Wikipedia

BOOKS

Northern Light: Nordic Art at the Turn of the Century Zorn: Paintings, Graphics, and Sculpture

Zorn: Paintings, Graphics, and Sculpture Landscape Painting

Landscape Painting

by Birge Harrison

Color and Light: A Guide for the Realist Painter

Thanks, Tim Adkins for the palette photo.