I’m told it’s relatively easy these days to render a photo-real character in CGI—as long as that character stands by itself. But to have one CGI character throw a bucket of water on another and then grab him by the shirt….well, now that’s a challenge.

How about having a couple of figures wrestling with a snake, as in the classic sculpture

Laocoön? How would a computer deal with the complex muscular dynamics and surface interactions?

In 3-D computer animation, this problem is sometimes called interactivity, and it’s one of the frontiers that is engaging the finest minds of the business. When Jeanette and I visited some of the post-production special effects houses last fall, like ILM, Imageworks, and Rhythm and Hues—or the CG animation outfits like DreamWorks and Blue Sky, I often asked what is the toughest problem to solve in CGI: Hair? Foliage? Fabric? Water?

On their own, each one of these “holy grail” materials is really coming around. The real challenge is to have these effects interact with each other, to have a couple of figures in loose tunics mudwrestling at the edge of a swamp, or a burning flag flapping in the wind.

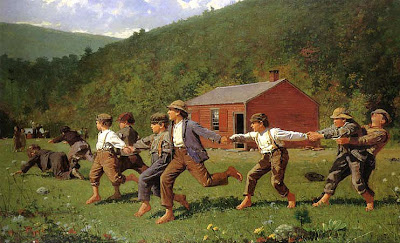

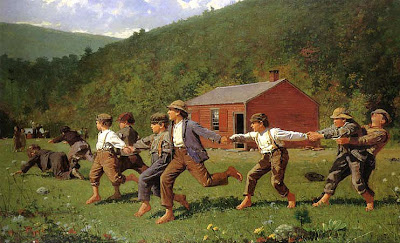

In the painting by Homer above, consider the physics involved in a scene of kids running and holding hands while cracking the whip. Each figure is both self-propelled by the feet, but also externally propelled by the large system of forces delivered through the hands as the momentum builds.

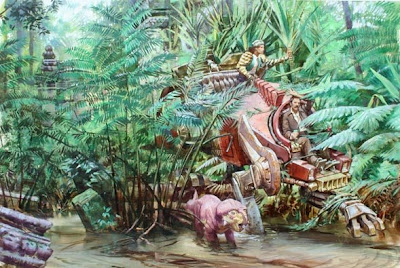

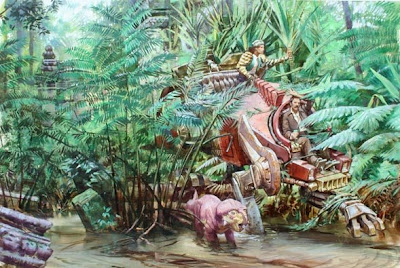

I was thinking about maximizing interactivity when I painted this scene from

Dinotopia: The World Beneath. A walking vehicle wades through water and weeds. Painting it is no big deal, but realizing it in CGI would take some doing.

One figure is pushing on a palmetto (1), while another is brushing away a fern (2), while the leg of the walking vehicle is dragging some plants out of the water (3), while the other leg is splattered with mud and half-submerged (4), while the body of the vehicle is pushing aside another stand of plants.

I can only speak with any knowledge as a painter, but I have wide-open admiration for my brother artists and scientists in CGI. Their work excites me because it’s the meeting point of art, physics, mathematics, and materials science.

The advances and challenges in CGI causes us to think about the visual world differently. The geeks behind the scenes who are making the big contribution in this arena don’t get the credit they deserve because their work doesn’t seem as glamorous or comprehensible as the work of the visual development designers.

When you watch the credits roll by on the next CG animated film, give a cheer for the people that figure out the science behind interactive effects.

------

Read about our visits to the movie studios last fall,

link.

In the story of Noah, the rainbow serves as a sign of God’s promise that the earth will never again be flooded. In the Stuppach Madonna by Matthias Grünewald (c.1475-1528), above, or the painting by Joseph Anton Koch (1768-1839), below, it serves more broadly as a symbol of God’s covenant.

In the story of Noah, the rainbow serves as a sign of God’s promise that the earth will never again be flooded. In the Stuppach Madonna by Matthias Grünewald (c.1475-1528), above, or the painting by Joseph Anton Koch (1768-1839), below, it serves more broadly as a symbol of God’s covenant.

Durer’s famous engraving Melancholia features a rainbow, though scholars differ on whether to read it as a hopeful or a pessimistic sign.

Durer’s famous engraving Melancholia features a rainbow, though scholars differ on whether to read it as a hopeful or a pessimistic sign.