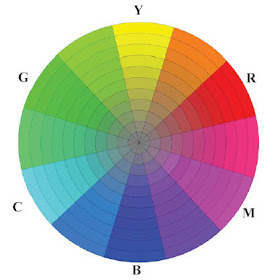

These latter three colors, (RGB), are significant, because they are the essential colors of light, as opposed to pigment. Mixing red, green, and blue lights together on a theatrical stage or on a computer screen results in white light. Green and red mix to yellow. Blue and green mix to cyan. Red and blue make magenta.

These latter three colors, (RGB), are significant, because they are the essential colors of light, as opposed to pigment. Mixing red, green, and blue lights together on a theatrical stage or on a computer screen results in white light. Green and red mix to yellow. Blue and green mix to cyan. Red and blue make magenta. The wheel was originally created by the photographer Tobey Sanford. I’ve spun it around to put yellow at the top and flipped it to put red on the right. Like those who work with theatrical lighting or computer monitors, Tobey regards red, green, and blue as his primaries. Yellow, magenta, and cyan are his secondaries.

You Ride My Bus, Cousin Gus

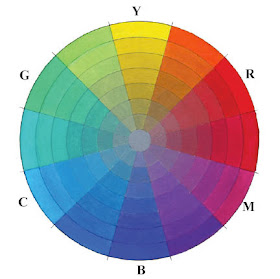

I tried to reproduce the wheel with oil colors, graying them toward the center. The colors shifted a bit when I photographed them, so the steps don’t look perfectly even here.

Placing RGB on the wheel evenly between CMY creates a color wheel that matches up with the color space in Photoshop. Now all those color balance sliders make sense.

You could name all twelve sectors, but for convenience, we’re just identifying six: yellow, red, magenta, blue, cyan, and green. The way I look at it, they should all be regarded as equal primaries.

Counting clockwise from the top of the wheel, they are YRMBCG. You can remember them by saying “You Ride My Bus, Cousin Gus.” For short you can call it the “Yurmby” wheel.

The “Yurmby” Wheel

Should painters adopt this six-primary color wheel? I believe it’s very helpful, as long as we keep in mind from the start that this color wheel—or any color wheel—is just a mental conception, a way of placing colors in your head.

We have to get used to red and yellow as closer neighbors than they were on the traditional artist’s color wheel. We have to get in the habit of recognizing and naming magenta and cyan separately from red and blue whenever we see them in art or nature. Unless you’re already accustomed to the Yurmby wheel, that means rewiring your brain. It has taken me a long time to rewire mine.

There’s a lot you can do with the Yurmby wheel. It makes a cool dartboard in an artist’s café. Also, you can chart where your pigments really appear on it. You can use it for gamut masking. I’ll show more of these applications in future posts. What I love most about it is that connects the worlds of computers, pigments, photography, printing, and lighting.

--------

Reviewing the posts in this series:

Part 1: Wrapping the Spectrum

Part 2: Primaries and Secondaries

Part 3: Complements, Afterimages, and Chroma

Part 4: Problems with the Traditional Wheel

Part 5: The Munsell System

Part 6: Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow

If you’re checking out this series for the first time, don’t miss all the comments, too, which shed light and bring interesting discussion and further links to many of the points.

I thank Tobey Sanford, with whom I've discussed this stuff at length. I’m grateful to Bruce MacEvoy of handprint.com and David Briggs of huevaluechroma.com, who have explored much of this material in greater nuance and depth than is possible here.