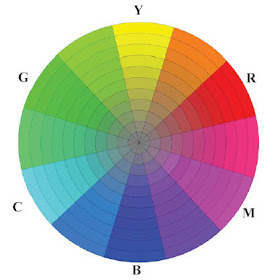

These latter three colors, (RGB), are significant, because they are the essential colors of light, as opposed to pigment. Mixing red, green, and blue lights together on a theatrical stage or on a computer screen results in white light. Green and red mix to yellow. Blue and green mix to cyan. Red and blue make magenta.

These latter three colors, (RGB), are significant, because they are the essential colors of light, as opposed to pigment. Mixing red, green, and blue lights together on a theatrical stage or on a computer screen results in white light. Green and red mix to yellow. Blue and green mix to cyan. Red and blue make magenta. The wheel was originally created by the photographer Tobey Sanford. I’ve spun it around to put yellow at the top and flipped it to put red on the right. Like those who work with theatrical lighting or computer monitors, Tobey regards red, green, and blue as his primaries. Yellow, magenta, and cyan are his secondaries.

You Ride My Bus, Cousin Gus

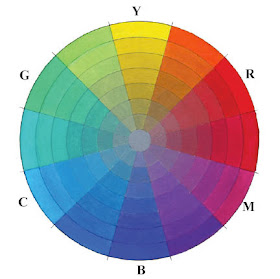

I tried to reproduce the wheel with oil colors, graying them toward the center. The colors shifted a bit when I photographed them, so the steps don’t look perfectly even here.

Placing RGB on the wheel evenly between CMY creates a color wheel that matches up with the color space in Photoshop. Now all those color balance sliders make sense.

You could name all twelve sectors, but for convenience, we’re just identifying six: yellow, red, magenta, blue, cyan, and green. The way I look at it, they should all be regarded as equal primaries.

Counting clockwise from the top of the wheel, they are YRMBCG. You can remember them by saying “You Ride My Bus, Cousin Gus.” For short you can call it the “Yurmby” wheel.

The “Yurmby” Wheel

Should painters adopt this six-primary color wheel? I believe it’s very helpful, as long as we keep in mind from the start that this color wheel—or any color wheel—is just a mental conception, a way of placing colors in your head.

We have to get used to red and yellow as closer neighbors than they were on the traditional artist’s color wheel. We have to get in the habit of recognizing and naming magenta and cyan separately from red and blue whenever we see them in art or nature. Unless you’re already accustomed to the Yurmby wheel, that means rewiring your brain. It has taken me a long time to rewire mine.

There’s a lot you can do with the Yurmby wheel. It makes a cool dartboard in an artist’s café. Also, you can chart where your pigments really appear on it. You can use it for gamut masking. I’ll show more of these applications in future posts. What I love most about it is that connects the worlds of computers, pigments, photography, printing, and lighting.

--------

Reviewing the posts in this series:

Part 1: Wrapping the Spectrum

Part 2: Primaries and Secondaries

Part 3: Complements, Afterimages, and Chroma

Part 4: Problems with the Traditional Wheel

Part 5: The Munsell System

Part 6: Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow

If you’re checking out this series for the first time, don’t miss all the comments, too, which shed light and bring interesting discussion and further links to many of the points.

I thank Tobey Sanford, with whom I've discussed this stuff at length. I’m grateful to Bruce MacEvoy of handprint.com and David Briggs of huevaluechroma.com, who have explored much of this material in greater nuance and depth than is possible here.

While I found the series both entertaining and instructive to read (which applies to so many posts in this blog!), I still feel a bit lost as to how to put this information to use.

ReplyDeleteThat's why I am pretty excited about your announcement for application examples. I mean, how does the new "all colors are created equal" approach affect actual color palettes and all?

Looking forward to this!

This is a great wheel and I think it makes more sense than the YRB wheel.

ReplyDeleteThis is the wheel that Corel Painter has used all along, but I never paid much attention to it's layout before.

I think I had a eureka moment.

Thanks!

I'm in concordance with you on this. After school I added a more cyan blue and a magenta to all my palettes. I noticed hues in nature that I was unable to achieve by mixing the traditional ryb primaries such as blooming magenta ice plant and certain colors in the sky and water. I try to keep my digital and traditional palettes similar, so this in turn helped my color in the digital space (over-saturation can be a problem sometimes).

ReplyDeleteThanks for the great series of posts Jim!

Thanks for the great overview of color from this past week. The final color wheel makes the most sense, it's amazingly simple and comprehensive.

ReplyDeleteIt's very interesting! earlier, I cannot undarstanding how is formated this beautiful colours! =)

ReplyDeleteIt is very good paintings for the sharing. I like it very much as well as your blog also. Keeps it up good work!!!!!!!!!

ReplyDeleteThanks for the intro to Tobey Sanford's site. It had many interesting images, among them a great photo of some young painter working at the Grand Canyon, although I think he was identified as the DinotopHia artist...

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete(Sorry, wanted to slightly tweak my post after I posted it, of course, but comments can't be edited, so I had to delete my previous one and post again. :)

ReplyDelete-------------------------

Thanks for these posts, James. Your site is always very informative and fun, and one of the best blogs on the internet in any category, period.

I did want to point out that the major weakness of this "opposing primaries" approach to mixing as demonstrated by these (and other) color wheels is the imprecision of color names, particularly when crossing paint manufacturer boundaries. Which yellow and which blue, for example, do you mean by "Y" and "B" on this wheel? Even if you use a color name like "yellow ochre," you will find that no two manufacturers' yellow ochres are the same in terms of hue, value and chroma, and sometimes they can really be startlingly different. This makes the utility of color names like "yellow ochre" very small, except as very general concepts.

If you projected a spectrum onto a wall and independently asked 100 people to stick a pin at the point they consider "blue", you would get pins in 100 different locations - close, probably in a cluster, but naming colors at that level is much more a psychological process than scientific.

In theory, pairs of complementary pigments may pass through a neutral (gray) core at the center of a color wheel (at a certain value at least), but in practice, any particular pair of pigments that you buy will not be perfect complements, and this means that you will get hue shifts when you attempt to create a gray (or any other specific target). Unless you are lucky, you will almost always need at least a third pigment to correct the hue shift introduced by the combination of the near-complements, and sometimes a fourth.

For general painting where tight precision of color is not a high priority, these general concepts are fine, but one of the main strengths of the Munsell system is that it provides a language for precisely describing color (e.g. "6.8B 4/12" instead of "blue"), and with that, a model for mixing with a very high degree of accuracy, independently manipulating hue, value or chroma while holding the others steady. The Munsell Student Book is very affordable and provides one of the most lucid texts on color theory that I've ever read, getting right down to the science of optics and wavelengths and building up from there, with exercises and examples. Margaret Livingstone's "Vision and Art: The Biology of Seeing" is another exceptionally readable book on light, color, and why and how we see the way we do, and what its implications are for art and artists. And of course David Briggs's site is brilliant, and the color theory section on Handprint.com is also extremely informative.

Thank you again for this interesting series color, and your outstanding blog which is always a joy to read. I'd encourage everyone who is interested in color theory to keep reading and learning. It's fascinating and well worth the effort. :)

Excellent series. It’s fascinating to see how painters think about color. As a photographer, I think of primaries as colors that cannot be divided further with a prism. That would be red, green, and blue. Put yellow through a prism and you get red and green. Put green through a prism and you get green, therefore green is a primary. Thus in Photoshop, we can make any color simply by adjusting the mixture of those three primaries – except for the limitations imposed by printers and monitors. Mixing pigments is much trickier of course, but I think it safe to say that painters have colors not available to the photographer.

ReplyDeleteI don’t use color wheels, but the Yumby wheel is the only one that makes sense for photographers as the RGB primaries are opposite their true opposites. To take out yellow, you add blue; to add cyan you subtract red, and so on. However, I noticed on your painted version the “primary” blue is not as saturated as on your painted Munsell color wheel. Is that due to matching a web image or is there another reason? Wouldn't that "primary" blue come straight out of a tube?

Walter--Thanks for those fascinating comments. The blue on my painted wheel doesn't look saturated enough only because of my lame photographic (and Photoshop) skills. It looks pretty good on the painted wheel, and I'm sure the lithographers at the publisher will get it right in the upcoming book.

ReplyDeleteSlinberg- great comments. I have to digest them a bit and I'll try to get back.

Thanks, everyone else.

"As a photographer, I think of primaries as colors that cannot be divided further with a prism. That would be red, green, and blue. Put yellow through a prism and you get red and green. Put green through a prism and you get green, therefore green is a primary."

ReplyDeleteWalter, I'd recommend you read Livingstone's book from my previous comment. You've got a couple of significant errors here. Wavelengths of light cannot be split; Newton demonstrated that by putting white light into a prism and splitting it into a rainbow, and then discovering that none of the colors of the rainbow could be further split. Spectral yellow light put through a prism remains yellow.

If you're splitting yellow light and seeing red and green, that means that that yellow light had components of red and green light to begin with. Actual yellow light from a prism can't be split any more than red or green could. Since our eyes cannot see light wavelengths in the way our ears can hear individual notes in a musical chord, we cannot tell the difference between yellow light from a prism and a "chord" of yellow light formed by combining other wavelengths. However, it should be clear that any color can be formed by combining various other wavelengths, so no individual color is special in that regard.

The discussion of why there is actually no such thing as a primary color, from a scientific perspective, is somewhat complex, but it's beyond dispute. It's all just wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum, and none of them are "special" or "primary". Our eyes are optimized, in certain physical senses, for processing wavelengths in areas we refer to as blue, red and green, but there is nothing inherently special about them, and no difference from other wavelengths other than, well, the wavelengths. :)

Read Livingstone's book. It's fascinating and it explains all of this very neatly.

Been playing around with the gamut masking idea with pleasing results. Curious to know how you can use a yurmby wheel for masking when the opposing colors aren't pigment complements - I guess you would just alter the mask shape to suit? Somehow? My brain's lodging a formal protest against that - it's staging a sit-in until it's resolved.

ReplyDeleteRichard, it's the fact that the opposite colours are not paint-mixing complementaries but exact additive complementaries that makes the, ahem, Yurmby wheel arguably the best choice for deciding questions of colour harmony. It's light stimulus, not paint, that reaches our eyes, and all visual colour interactions - including successive contrast and afterimages, classic simultaneous contrast, coloured shadows, assimilation, optical mixing, and so on - follow additive complementary relationships, not paint-mixing complementaries.

ReplyDeleteThe Munsell hue circle is (I believe) nearly as good for this purpose, as its opposite colours depart only a little from exact additive complementaries. The Yurmby wheel is not as good as the Munsell hue circle for absolute specification of hue, because the precise hues of the red, green and blue/violet primaries are arbitrary. Nevertheless, anyone wanting to find exact additive complementaries of any given colour need only bring up the colour in the Photoshop (or similar) colour picker, and inspect the range of colours (of varying lightness and chroma) with H differing by 180. (In this connection it makes no difference what the precise R,G and B primaries are, as long as R255 G255 B255 looks neutral).

David Briggs

It's always an honor to have your comments, David, as your site "HueValueChroma.com" is one of the best sources of info on color and light on the web.

ReplyDeleteAnd I agree with your point--in fact the argument on your website won me over. A "pigment relationship wheel" isn't really as meaningful as one that tries to mirror the effects of color in the realm of light and perception——especially since ultimately we're concerned with the painting's effect on the eye, and it doesn't matter as much how we get there.

Slinberg, in an earlier post, was correct to point out my mistake in implying that red, green, and blue are the only colors that cannot be divided with a prism. I was thinking of the colors on the James’s Yurmby color wheel; that all but red, green, and blue are composite colors in the additive sense. But to the extent those "composite" colors can be divided with a prism is indeed another matter.

ReplyDeleteJames was being kind when he called my comments “fascinating”. Maybe he was just wondering where I got my prisms. : )

David Briggs just set off another bomb in my head: the notion that a painter really needs two color wheels which will not be the same: one as a guide for mixing, with an effort at aligning subtractive complements across the wheel from each other, and one for choosing harmonious color sets for what the painting will look like once it's been painted and it's just the light hitting our eyes from it that counts.

ReplyDeleteI need to let that ricochet around my brain for a little while and see where it all settles. :)

I will also need to do some research and testing to find out how well the Munsell wheel does with opposite subtractive complements. Time to dig into the student book a little more...

(Walter: thanks for taking my comments in the spirit they were intended :)

Red Green and Blue are the primaries of light whereas their opposite colors, cyan, magenta and yellow are the primary colors of pigment (as those in offset printing know). If you shine a red light and a green light and a blue light together at something it produces white light (as those in stage lighting I would presume would know), that's why it's called additive color. Whereas with pigment adding primaries together have the opposite effect, that is why it is referred to as subtractive color and light is referred to as additive color. So, rather than red being the opposite of green and yellow the opposite of violet and blue being the opposite of orange as we are traditionally taught gives way to a color palette where red is the opposite of cyan, yellow is the opposite of blue, and green is the opposite of magenta.

ReplyDeleteThanx James for such an fun series of posts! You’ve done a great job mapping this all out for us, and your blogosphere is filled with some very high flyers.

ReplyDeleteYour “Yurmby” wheel does a great job of bridging the gaps between the three media: light, inks, and pigments… but at a high price to the colored-mud manipulators; and the overall warm/cool balance feels a little askew to me. But my biggest problem is not just with the closer relationship of yellow to red (they have always had a warm and intimate relationship) … but with the loss of the Yellow/Purple opposition. I understand that the CMY(Inkboyz)*, and the RGB(Lightboyz) place blue in opposition to yellow, but the loss of the yellow/purple opposition for the YRB(Mudboyz) results in mixing-down these two colors into greens, and this is very unsatisfactory! [i almost went w ‘Pigboyz’, but that’s a little to close to home… and a little over the top, even for me];-

*I mean this in terms of the royal ‘Z’, no exclusion intended of the Artgalz, (Margaret Livingstone has set the bar pretty high with her book: "Vision and Art: The Biology of Seeing," I strongly recommend it!)

< We have to get in the habit of recognizing and naming magenta and cyan separately from red and blue whenever we see them in art or nature.>

I have no problem with this, and I am also fine with letting go of the limitations of referring to colors as ‘primary,’ at least in terms of cross-platform mapping (however, I don’t want to thro the baby out w the bathwater when it comes to mixing mud). Raising Green to the level of a ‘primary’ is actually a really good idea, since she is the Queen color in Nature and our eyes are adapted to recognizing a huge range of greens, and to distinguishing very subtle differences within the green spectrum… but where does that leave Orange and Purple? Not only are these two ‘Primary’ colors under represented on ‘Yurmby’ (with only one position each on the chart), but they are diminished at the over-emphasis of greens, blues, and reds (with three positions each on the chart).

Your excellent analysis of the overall problem has caused me to fine-tune my approach to the color-map, and I think I have come up with a good compromise.

My approach to color mixing is to arrange the color-map in terms of warm and cool relationships, then each color can be represented as two values:

Cool-Yellow / (Arylide Yellow)

Warm-Yellow /(Cadmium Yellow)

Orange /(Cadmium Yellow + Quinacridone Red): Like the ‘Yurmby’ wheel, Orange is limited to one position on the map.

Magenta (Cool-Red) / (Quinacridone Red)

Warm-Red / (Cadmium Red)

Cool-Blue / (Ultramarine Blue): I know some folks consider Ultramarine a warm color, but with its transparency and dark register, it feels and acts cool to me.

Cyan (Warm-Blue)/ (Cerulean)

Violet (Cool-Blue) / (Ultramarine + Quinacridone): Newton’s Violet is back!

Warm-Purple / (Quin. + Cobalt … it just makes a crisper purple than w Cerulian.)

Cool-Green / (Arylide + Ultramarine);

Green / (Ultra. + Cad. Yellow or Cerulian + Arylide): Green is expanded to three positions, as on the ‘Yurmby.’

Warm-Green / (Cad. Yellow + Cerulian)

While this approach is not perfect, it is a good compromise and maintains all of the opposing color relationships for the cross-platform systems:

CMY and RGB have a yellow (warm) in opposition to a blue (cool); and Cyan opposes a red (well… a yellowed-red, I said it wasn’t perfect, but it’s still a red, sorta).

And… YRB has a cool-yellow in opposition to a cool-violet, while Orange opposes a warm blue (Yes, I know its Cyan to you, but it’s a warm-blue to me).

If this is too cumbersome, a similar map can be created by modifying the Munsill wheel: simply change the RP to Magenta, and the BG to Cyan. (Wow, that works pretty good, maybe I should have started w that!)

Thanx again Jimmy G. for your fun blog. And Thanx to my fellow Journeyers, I look forward to checking out David’s "HueValueChroma.com" site in more depth when I get a chance. -RQ

Roberto, I'm glad you mentioned Margaret Livingstone's book. I'm reading it right now, and you're right, it's a concise presentation of the latest science, most of which hasn't been absorbed by the artistic community yet.

ReplyDeleteI'll agree with you that the Yurmby wheel that I have posted looks too cool, and I think that's a result of my failure to photograph it well. I'll try to reshoot. Beyond that, the color distribution can become caught up in semantics: what's a blue or a green? That's where the digital wheel above is better, because the color distribution is arrived at mathematically. But the goal is still to space them apart so that they make perceptual sense.

The optical wheel seems weird at first. What won me over to it was the thought that I wanted to map the actual perceived colors of the picture, the way color relationships are experienced by the viewer. Color vibration in the painting should follow optical (additive) complements, not pigment mixing complements, because that's how the eye really sees it.

How you mix or arrive at the colors in the painting doesn't really matter, and I don't look at the color wheel when I'm mixing paint, only when I'm planning the composition and getting started. And as us Colored Muddists all know, mixtures do funny non-linear things anyway, like the way white shifts oranges and reds toward blue.

Thanks everyone else for your very helpful comments.

James-

ReplyDeleteYour right about the color relationships in the composition being the most important aspect of any conversation about color for artists. It’s what you do with color, not necessarily what you intellectualize about it. Results vs. Angst, Results win.

I am currently exploring Stanton Macdonald-Wright’s ‘Treatise on Color’ and his

‘Synchromism’ theory for equating hues w musical notes and composing w color-chords, creating dominant, sub-dominant, tonic, major, and minor chords, and transposing compositions into alternate keys. Stanton worked w Morgan Russell and studied color under Tudor-Hart prior to WWI around 1912-1915 (Cubism and Blue-Riders?), and exhibited at Stieglitz’s “291” gallery. I’m not a big fan of his painting style, but his ideas about color and music are intriguing.

I look forward to reading your forthcoming book on color and light.

Creatively yours -RQ

Coming late to the party; hope someone reads and responds to this. I recently discovered the Yurmby wheel via James' book and it does kind of blow my mind. I feel as though it resolves a discontent I'd had with the traditional wheel though I never would have been able to articulate what that discontent was. Adding magenta and cyan feels like a fresh infusion of oxygen.

ReplyDeleteHowever, having painted one out, I find myself wondering whether it might not be just as well to use the 10-hue Munsell wheel after all, with cyan and magenta in the BG and RP spots, as suggested above. I gravitate to this for two reasons: 1) that way you actually do get mixing complements across the wheel, no? 2) On the 12-hue Yurmby wheel I've painted out, I feel like the cool sequence from PB to Green makes finer distinctions than absolutely necessary. The Munsell wheel looks more balanced between warm and cool, and more evenly sequenced, to me.

So that makes sense to me, except that even though James writes in his book that many artists use the Munsell wheel, I don't know of any who do and have never seen a book that recommends it. James goes into no detail about how it might be used, and his preference for the Yurmby is obvious.

Any comment, anyone? Are there any downsides to using the 10-hue Munsell wheel?

Cavorting, never too late to join the party. I have no problem with the Munsell wheel, in fact in some ways it's better for painters because as you noticed the complements are designed more for pigment mixing. The complements on the Yurmby wheel are more geared for mixing of light and the physics of visual perception. I use the color wheel as a mental map of the color universe and as a way of planning color schemes, but if you use it as a guide for mixing, I'd go with the Munsell wheel.

ReplyDeleteWow, thanks for the speedy response. Now, I don't absolutely need a wheel to guide me in mixing complementaries, I just threw that in as a convenience of the Munsell. What was troubling me about the Yurmby was what I described as "making finer distinctions" among the cools than the warms and what Roberto described as "over-emphasizing" the greens and blues.

ReplyDeleteIt's true that, as a painter, I don't require the special utility of the Yurmby for mixing light. But what will I be missing out on if I try to use the Munsell "as a mental map of the color universe and as a way of planning color schemes"?

I want it all!

Thanks a lot for this great blog.

Thank you so much for this series. I'm an art student half way through my degree and I've had to teach myself colour theory completely on my own.

ReplyDeleteIn defence of the addition of cyan and magenta to our basic colour vocabularies: I have a linguistics background, and I think it's worth remembering that language has contributed to our understanding of colour, particularly regarding which colours are the primaries or basics. (I disagree with the hypothesis that colour names are evidence for a strong version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis however.) For example, Russian doesn't have one word for blue, distinguishing between a cyan-like light blue and a dark royal blue (goluboy and siniy). Italian, Turkish and Greek similarly distinguish between cyan and dark blue as basic colours. (Our word azure comes from the Italin azzuro.)

Many thanks for recording and describing this system of colour control. Limiting colour is little taught and relies on an intuitive understanding that we don’t all come by, even if we have other skills. Much appreciated.

ReplyDeleteA few questions if you don’t mind (perhaps some can be answered at the same time as they overlap but I’ve spend years painting and am still frustrated at my attempts with colour harmony- so if you could answer them i hope to fill in some holes in my education.).

1 How did you get the colours that sit between the primaries (i.e. the secondaries)? Did you just mix the two colours you chose to be the heads of the families: like A and B and mixed them to get C ( the secondary ) or did you mix A and B along with different tube colours until you found something you liked? This assuming the tube colours you chose exist in their strongest hue on the periphery of the larger colour wheel and are used here only in very desaturated values but still lie inside the gamut shape.

Or, is the secondary colour an entirely different, desaturated hue/colour, it’s hue uninfluenced by it’s neighbours. In this case the secondary would just be a greyed down value of the outside colour that sits between A and B on the periphery (as mentioned above).

Influenced Gamut: http://budovitch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/gamut.jpg

3 When trying to re-create your gamut on the colour wheel (supplied from the Richard Robinson website) the colours have visible bands, or ”levels" of saturation as they head away from the centre. Are these “steps" made by just using greys or are neighbouring colours influencing each other? Or are complimentary colours being used to neutralize the chroma?

4 This quote is pulled from your blog:

"Now you’ve created the “heads of the families” or subjective primaries. Next, extend those colors into four different values or tones. Try to keep the hue and the saturation constant as you do so.”

How are the hue and saturation kept constant? Just varying the amount of grey?

5 When the sun sets over a town, all the colours are washed in a warm yellow light. Would this not be enough to maintain colour harmony without limiting your palette? I think of it as the “mother” colour system.

6 If a tube color’s natural value places it not on the periphery of the colour wheel with the primaries but closer to the centre and within a chosen gamut, do you grey it down or use it full strength, tinting and shading it to create it’s own colour string?

6 Where did the fourth colour string come from when you created your “triad” gamut here: http://budovitch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/gamut4color.jpg

I believe the triad comes from the gamut and the fourth colour string is needed to finish off your set of primaries ( YGBR)?

7 In reviewing your book I was examining this colour palette you created from a gamut. There appears to be much stronger and more chromatic options available in the gamut. Certainly colour reproductions change. Humans aren’t perfect but it appears you could have had at least 7 significantly different colour families to work with. Based on Richard Robinson’s gamut-making application and the gamut you chose you could have even more choice. But at this point you’re not limiting your palette as much.

Could you please explain the discrepancy? http://budovitch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/gamut3.jpg

Ericbud, a lot of good questions here. With your last one, you're right, it's really hard to reproduce these wheels whether online or in print--that's one of the reasons it helps so much to paint our own wheels. I use the highest chroma tube colors I can find to paint the wheels, and mix adjacent hues if I need to shift hue. In #6 you brought up value, and of course all these wheels ignore the dimension of value, which would go up and down vertically from a Yurmby wheel sitting on the table.

ReplyDelete"Blue and green mix to cyan"

ReplyDeleteDoes it really happen, either in light or pigment? To me it seems that cyan is the hue with the inherently lightest value and thus it would be like an "absolute" primary in a way, at least in its most saturated form. Whereas green and specially blue are inherently darker. Dark + darker = lightest?

The other two "absolute primaries", if it's true that we can't get lighter from darker value, would be yellow and magenta. That's interesting.

ReplyDeleteI'm confused about the complementary colours.

ReplyDeleteI've been told all my life that the complementary colours are for example red/green. These derive from the traditional RYB colour wheel.

But I have been learning that the RYB colour wheel is outdated and that a colour wheel based upon cyan/magenta/yellow primaries is more optimal. That gives us complements of red/cyan etc.

Doesn't that mean that red/green aren't really complements? That everyone's getting it wrong?

Hope someone can enlighten me!

Mellie, the subject IS confusing, there's no way around it. That's because we're dealing with the intersection of visual perception, paint chemistry, and optics. One has to chose which of those systems governs the choice of complementary pairs. For example, blue and yellow are perceptual complements, but blue and orange are pigment opposites. The problem with choosing pigment properties to create a color wheel is that mixtures drift warmer and cooler on their way to a neutral point, and it depends on the pigment. You can read more about this on David Briggs' excellent website HueValueChroma: http://www.huevaluechroma.com/061.php

ReplyDeleteNo need for two separate wheels. The behavior of individual pigments is too complex to be predicted by ANY mixing wheel, so I would use the YURMBY wheel for visual design and intuitive or other non-wheel methods for pigment mixing strategies. Mixing wheels are bunk!

ReplyDeleteBruce MacEvoy at handprint.com has published an excellent chart of mixing complements. The chart shows all viable neutralizing pigments for each cool pigment, how dark the mixture will go, and what hue bias it might have, if any, and how much. From this chart, you can choose a handful of neutralizing pigments to use in tandem with your visual complements. This chart is gold! It's made for watercolor, but is still quite useful for those using other traditional media. Click on Color Theory, then Watercolor Mixing Complements.

Thanks, Robin. That's a really helpful comment!

ReplyDeleteI still need a better explanation of the comparison of warm versus cool colors

ReplyDeleteMifasola, please try this post, with its comments: https://gurneyjourney.blogspot.com/2007/12/color-warm-and-cool.html

ReplyDeleteI can't believe this post is 8 years old... Regardless, I'm curious if you know where I can purchase a durable (possibly plastic?) YURMBY color wheel? It seems a lot of the links provided in the posts either link incorrectly or are gone, specifically those providing a place to obtain the YURMBY wheel, Tobey Sanford or Alias 3D Media.

ReplyDeleteAt this point I'm probably just going to make my own. What value should I make the center grey? A 5 on a 10 scale? As the colors grey towards the center my monitor shows they look to be adjusting in value towards a 5 (blue goes lighter, yellow darker) Is this correct or should I be trying to maintain the original value of the color (i.e. yellow will stay at a lighter value than blue)?

James your explanation of the yrmb wheel in your book light and color changed my life. It's such a great way to make cohesion in the palette aswell as knowing how to move a color. What always gets me though is how do you make grey from yellow and blue, that part of my mental wiring is the last hold out. Must have had an impactful kindergarten teacher haha take care

ReplyDeleteChris, you're right to question that. Yellow and blue pigment make green, not gray, as you probably suspected. However, a royal blue is opposite to yellow (not orange) in the machinery of the eye. You can test this for yourself by looking at a blue square for 30 seconds, and then let your eyes move to a white area below it. What color does it appear to be?

ReplyDeleteThe argument of thinking in terms of blue-yellow complements when painting is that you might as well optimize your image to the behavior of the eye rather than the behavior of the pigments, because that's what matters to the viewer's experience.

Patrick, I just painted my own YURMBY wheel. It was a great learning exercise, which is half the purpose of it.

ReplyDeleteThere's still this free digital version I made: https://www.livepaintinglessons.com/gamut-mask/

ReplyDeleteThank you for renewing interest in this color wheel. Many years ago I discovered ''The Real Color wheel'' www.realcolorwheel.com. It makes many scientific and clear examples for the same principles you outline here. Plus has a very good printable color wheel I keep in my studio and a little one in my plein air supplies. Please notice how he shows ultramarine blue turns to brown with the opposite yellow/orange on that wheel.. Then notice how many painters have used that complement very successfully in paintings! (-:

ReplyDeleteThank you, Richard Robinson, for sharing the link to print the color wheel. I have been teaching all my students to think this way for many years with success. I did photo print-retouching and used only Indian Yellow, thalo blue, and Perm rose to airbrush and keep the paint invisible and transparent on the prints. (I had studied Maxfield Parrish's layering techniques and glazing by the old Masters). I used the principles to paint in oils.

ReplyDeleteThere are many 'convenience' colors, to minimize mixing, but I trust I can get by with just these three, plus a smidge of thalo green to make a true cyan. Your color wheel was the correct scientific affirmation I was looking for.

Coming from an architecture background rather than fine arts, I've been relearning contemporary Color Theory anew. When I ws in school in the 70s "theory" was a cardboard Artist's Color Wheel. While my thinking of "paint" is Munsellian, the pervasiveness of Digital lends organizing "Color" in-accord with your YURMBY system logical, and it bridges to the HSV Universe of Digital Color.

ReplyDeleteAlso, YURMBY places the named-primaries at approx. 60/120-degree interval around the wheel to conceptualize how Color is organized. The intervals of Munsell-to-HSV angles are irregular but similar enough...

Hi James, Thank you for your fabulous book Colour and Light which I am enjoying immensely. It is delightful to find such a helpful and insightful book that brings light and clarity in relation to this complex topic. I am able to comprehend how the colour wheel relates to both additive colours for RGB or whether one wants to adopt the subtractive colours of CYM depending if you dealing light or pigment. Had to learn to be open to step away from the traditional RYB model introduced during childhood by those who are not familiar themselves to the subltle dynamics of colour theory.

ReplyDeleteBefore adventuring in experimenting with Gamut Mapping, there is one detail that I would like some clarification which is confusing me. In the Yurmby wheel as you reach towards the centre of the wheel, is the chroma being reduced because the complimentary colour is being introduced gradually more to each concentric arch? E.g If you have red at its highest chroma by the perimeter of the wheel, then as you reach the centre introducing the complimentary colour with a gradual increase of opacity until each reach 50/50 of each that you end up completely neutralising another?

Thank you for this article James. It really is fun to wrap your head around the idea of Subtractive and Additive colour models. Fascinating that orange is complementary to blue when mixing colour but that yellow is complementary to blue in the way we see. I found interesting that the science of after image is still not fully understood, with opponent process theory being the most likely answer: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afterimage

ReplyDeleteI put together a synthesis of this information with a few of my own thoughts into a video. I hope you don't mind me sharing: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HYmuc31Wog4 and thanks again for letting me feature your work! You are an inspiration as always.

Hello James, thank you for the article, how about the complementary color in the YURMBY wheel? like the traditional wheel, there are red-green, yellow- purple, and blue and orange?

ReplyDeleteAmos, quick answer is that the complements for your visual perception are not exactly the same as the pigment complements. It's more yellow-blue rather than yellow-purple.

ReplyDeleteThis article is brimming with information about selecting all of one color like this. I have additionally discovered an article anybody can check Select All of One Color , for more data, it was knowingly more instructive. You may discover more insights regarding it here.

ReplyDeleteHi James,

ReplyDeleteyou are sharing true gems by just reading my mind cracked...the comments are full of gold, thank you very much for sharing and nurturing this important knowledge! Miso