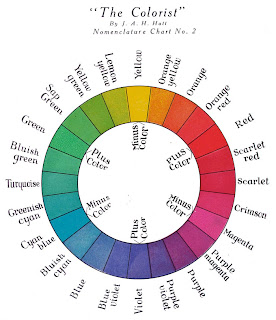

Here was a title I had never heard of before. The date of the book was 1908. What really grabbed me was the subtitle: “Designed to Correct the Commonly Held Theory that Red, Yellow, and Blue are the Primary Colors, and to Supply the Much Needed Easy Method of Determining Color Harmony.”

I bought the book, brought it home, read it, and was thunderstruck. Here was the very same theory that I’ve been developing on my own, and which I thought was new and revolutionary.

In essence, Hatt’s premise is exactly the same as mine: instead thinking of red, yellow, and blue as the primary colors, we should be replacing them with magenta, yellow, and cyan. (Note that what he calls "violet" is the same as what I call "blue" on the Yurmby wheel. The difference is a matter of semantics, and we're both talking about a kind of violet-blue.)

Anyway, printers in Hatt's day were just discovering this new was of thinking of the color wheel. They made the switch then and never looked back.

Magenta was a new color to the world of printing in Hatt’s day. He was acquainted with the chemist who developed one of the first formulations for magenta ink, and he warned readers of the book not to hold the pages open too long to sunlight, or the rare ink would fade.

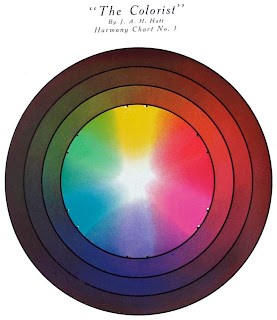

The second novelty of Hatt’s book is his method for developing color harmonies, using templates laid over a gradating color wheel. This also was a lot like the system I had struck upon independently, but instead of graying the color wheel at the center, his went to white in the middle, and carried dark tones in outer rings.

And according to the text of the book, there were supposed to be gamut masks or templates in the back of the book, but unfortunately, they were missing in my copy.

(My own work in the area of gamut masking owes much to Walter Sargent’s 1923 book, “The Enjoyment and Use of Color,” reprinted by Dover). Link to Amazon for Sargent's book here.

So what’s new is old, I guess. Anyway, you can read Hatt’s book yourself on a free downloadable PDF courtesy of Google Books.

------

--My book, due out in November, is: Color and Light: A Guide for the Realist Painter

--Wikipedia gives a good overview of the history of thinking about primaries

--And so does Bruce MacEvoy in Handprint.com

--(added) And David Briggs on HueValueChroma

--Previously on GurneyJourney (Feb 2010): Rethinking the Color Wheel

--If you live in the Pasadena, California area, please come to my workshop tomorrow, Sunday, that covers this stuff.

Interesting.

ReplyDeleteI've been pushing the Yellow, Magenta, Cyan thing since 1970, in the teeth of opposition from artists who believe that everything they were taught in school is eternally true. But I had no ida there was a book that far back - books on color printing from the 1920s talk about Red, Yellow and Blue inks.

I thought it was mainly the people like Yule at Kodak in the 1940s who clarified the terminology.

However, if you look at the actual inks used in the 1900s, they are really a rather dirty magenta and cyan, not scarlet and ultramarine blue.

I think the book "Colour" by Zelanski and Fisher was the first book aimed at artists that got it right.

I would argue that the whole concept of primary colors in paint mixing is a flawed holdover from the additive physics of mixing light rays, and a failure to understand that mixing paint is mixing pigments- not mixing colors.

ReplyDeleteThe problem is that with light, we can actually recreate the whole spectrum of light from 3 primaries, since adding lights together can "add up" to white.

There's no way to "add up" when mixing paint- mixing two colors together will always result in a mixture that is darker than the lighter of the two colors, and sometimes darker than both colors. The same goes for chroma. You can't mix a high chroma magenta with a high chroma yellow and get an equally high chroma orange. To get that orange, you would need to mix colors that are closer in hue, or just supplement a higher chroma orange pigment in the first place.

Using a cyan, magenta, and yellow *will* generally produce a larger gamut than a red, yellow, and blue- but it is still a fairly small gamut. Using a cyan, magenta, yellow, and green will give you a larger gamut. Should we consider green a primary, too? To take it a step further, all of the gamuts above would be fairly limited in terms of value without black and white. Even printers use K and white (the white of the paper). So should black and white be primaries also? In a sense, I would argue "yes" - it's better to think of your primaries as the colors that sit on the "corners" of the gamut created by all of the paints you are using at a given time. They are critical to achieving a given range of colors. Colors that are not primary are pigments that sit within the boundaries of your gamut, such as Yellow Ochre in a Cadmium-heavy palette.

CMYK (plus paper white) is a good compromise used by the printing industry- it's a small number of standardized colors that will produce a good size gamut for the number of colors used. The use of spot colors in printing and the current trend in inkjet printers using 6 or 8 or more colors indicate that CMYK is not sufficient in and of itself. We can't consider that those "three" colors can actually create all possible colors- just a good range for the small number of colors.

There's a further problem with the fact that pigments do not mix predictably based on their apparent color- there are a whole range of factors involved based on the complexities of the interactions of particles in paint. You could have two paints with the exact same hue, value, and chroma but made up of different pigments- they will produce different colors when each is mixed with a third pigment. In other words, "cyan" is a fairly abstract concept when it comes to paint. Even if we had a paint pigment with an ideal cyan color (we don't as of yet), it wouldn't necessarily mix in an ideal way with other pigments.

So, I would argue that the whole concept of "primary color" for painters needs to be rethought, or even eliminated.

Hi James. For an even earlier instance of your "revolutionary" theory checkout chapter V of:.

ReplyDeleteBenson, William, 1868. Principles of the science of colour concisely stated.

http://www.archive.org/details/principlesscien00bensgoog

Don and Briggsy, I know I'm one of the last guys on the train compared to you guys and the earlier folks you mentioned. Thanks for those links and leads.

ReplyDeleteAnd Tim, I really appreciate your taking the time to explain those very important qualifications and clarifications. The way I worded things in the post is very simplified and potentially misleading.

As you say, any subtractive primaries, even the CMYK used in the printing business, result in weaker mixed colors as a result of saturation cost, so the only way to get intense vibrancy across the full spectrum is to use additional printing colors.

Let me add and clarify, especially to my fellow traditional oil painters, that all this talk about rearranging the color wheel is somewhat academic for a couple of reasons.

Number one, we almost never need to paint a wide range of full chroma colors. Number two, we have available pigments with wonderful properties that don't match the CMY primaries and we should keep on using them. And number three, the behavior of complements in the additive and subtractive wheels don't match up, so when we're mixing real paints, the mixtures don't fall in line with the ideal wheel.

We can stick with the same paints that have always worked for us, but at the same time recognize that the Red-Yellow-Blue wheel we keep encountering in the art world is not the only way to look at the color landscape.

I neglected to mention that "briggsy" is one of the foremost authorities on color. His website "HueValueChroma" has that rare combination of depth and clarity. I've added the link at the end of the post, but here's the URL: http://www.huevaluechroma.com/

ReplyDeleteWow, what a neat find. That's why I love secondhand bookstores.

ReplyDeleteMuch of what Tim Dose says about CMY applies equally to RGB: the gamut is limited, and mixtures have lower chroma than the primaries.

ReplyDeleteI agree that trying to use primaries for mixing paints is pointless, as there is no real reason why you can have only three paints in your collection. When it comes to commercial printing, the cost of adding another press to give a fourth (or fifth) color is very high. So primaries are essential.

I think painters need to know about primaries because their work may be printed or shown on a screen, not because they are useful in painting.

Recent inkjet printers use more than three primaries.

i had a very long and drawn out discussion/minor argument with a friend about RGY vs CMY. I feel totally justified now! thanks for the validation. If it comes from you, a famous, established and kick-butt artist, it lends more credibility.

ReplyDeleteTiffany, thanks for the credit, but hat's off to Hatt.

ReplyDeleteI was also under the impression that Munsell also was doing away with the idea of primary colors as well.

ReplyDeleteI like the Munsell idea of the three dimensions of color.

Jeff, the idea of three dimensions is not munsell's, the fact that you need three is a physiological consequence of the way we perceive color. A general light wave is in fact defined in a infinite dimensional space (for the initiated, I am talking about the spectral decomposition), or at least a very high dimensional one, but we interpret some of those waves as the same colour (meaning we cannot distinguish the appearance of one from the other), in a way that loses information and reduces that space to only three dimensions (for most of us, at least; some people are weird like that!). Now, a 3-d space has many (infinite again) coordinate systems. Munsell proposes a specific coordinate system that happens to be good for lots of things, and quite intuitive - but the fact that it has 3 dimensions is certainly not his contribution.

ReplyDeleteJames: Don't fret, it happens all the time. It is good to come up with an idea all by ourselves, even when we find someone did it before after all. I've had that feeling a few times, and it's a bit frustrating, but the fact is that you came up with it anyway, and that is worth something! When you discover something independently you make it your own and you understand it better than if you just read it somewhere; and sometimes, thanks to that, you may find some small aspect of it that is in fact really new. There's just so many people and so many years behind us, there's very little new under the sun, and every little bit takes lots of work...

Oh, by the way, I remember you read at least a bit of handprint, right?...well, the reasons why CMY is optimal (in a very specific sense) for subtractive "primaries", the reason RYB isn't, as well as the sense in which primaries are useful in general or even make sense as a concept are very clearly explained there. I think it is in this section, or near it:

http://www.handprint.com/HP/WCL/color6.html

Basically no 3 colors can generate the whole color space (nor in fact can any finite number), what you get is a polygon in the color space. Some polygons will cover an optimal area (CMY is such a case) in a certain sense, but that is no consolation if the color you want is outside that area, and in that case you have to add more "primaries" to your n-gon. Basically each choice generates a certain span, and that's it. Also, when dealing with paints you got to fret about substance uncertainty, and so on, and all theory has to contend with such realities of real paints. Check it out at handprint, it's all there. Some of it is at "huevaluechroma" too; I can't stop praise those sites too much, and one day I will manage to read all of handprint, I swear :)

Actually, this is the section:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.handprint.com/HP/WCL/color5.html

search for "Ideal Subtractive Primaries" and you should find what you want. It is around the middle of the page. Better yet, read the whole chapter.

I must add to what I said before: it may seem like a contradiction to say that the space is 3d yet there is no set of primaries. Shouldn't there be a set of 3 generators? There is, but those 3 are not real colors, they are abstract constructs. Basically, if you get any 3 real colors, say RGB, there are colors X that you can get as X=aR+bG+cB, with positive a,b,c, and others you can't. But you can always get X+aR=bG+cB or variations thereof. So, equivalently, you write X=-aR+bG+cB. By finding the limits of this space you can change basis and find your 3 "good" generators, only because of the negative coefficients trick those generators are not real colors anymore. I cannot explain this better in a small space, again refer to handprint if you want to know more.

Well put, James. I'm looking forward to your book getting out there- it will go a long way to getting good information to a larger crowd, and hopefully dispel much of the misinformation out there (there's just so much!). So, thanks again for all your work.

ReplyDeletep.s. I feel I need to give credit for most of the info in my previous comment coming from Bruce McEvoy.

Getting very anxious about having your book. Thanks for this great heads up.

ReplyDeleteSorry, I never meant it was Munsell's idea, I was pointing out how his system is one of the best for describing color space. Sorry I should have been more precise in my comment.

ReplyDeleteMany commenters have differeianted between mixing pigments and bands of light - is there a good practical source for mixing pigments in oil - specifically oil - i have a great one for watercolor - "making color sing" but i have yet to find a good one for oil.

ReplyDelete>should have been more precise in my >comment.

ReplyDeleteJeff, that's fine, I'm the one who should be saying that, after that jumble I wrote up there. The only understandable part of that mess was the link! I keep breaking the rule of never writing while in a hurry, but one always seems to be in a hurry these days... :p

Red,Yellow & Blue are the ADDITAVE

ReplyDeleteprimaries.Cyan, Magenta & Yellow are the SUBTRACTIVE primaries.Commercial graphic arts printers use TRANSPARENT CMYK to filter out colors reflected from white paper to create the color desired.If you think you are adding color when you print, try using transparent CMYK on black paper and see what you do not get.The thing to understand is the difference between working with OPAQUE colors & TRANSPARENT colors.If you wanted to print on a black substrate you would use opaque ink.Titanium white , by the way,is used in ink to make it opaque.

There is a more advanced version of the Munsell system, known as the Optical Society of America Uniform Color Scales. This uses an orthogonal grid (like scaffolding) rather than a radial one, so there is no "color circle"; and the color samples are more evenly spaced.

ReplyDeleteJames, there is a lively discussion going on over this particular post of yours on the Rational Painting forum.

ReplyDeleteBasically, I asked there, what it could be that you found wanting in the Munsell system that caused you to look for an alternative system.

Of course the advice was to ask you. So I'm asking. What is "missing" in the Munsell system, from your perspective, that caused you to continue searching for another way?

Briggsy,

ReplyDeleteOn the other forum, you said that "Munsell is the most uniform available hue scale." Are you referring to uniformity in complementary color mixtures (i.e. producing grays) or uniformity in perceptual hue gradations? If the latter I would like to know what data you are basing that statement upon.

etc. etc.,

ReplyDeleteRolf Kuehni's books give excellent concise summaries of the development of the Munsell and other systems, but otherwise a good place to start is the popular-styled American Scientist article by Landa and Fairchild, which lists some of the most important references on the history of the Munsell system in the bibliography:

Charting Color from the Eye of the Beholder:

http://www.cis.rit.edu/fairchild/PDFs/PAP21.pdf

Basically the extensive testing of the system by Munsell's heirs and then by the OSA was for the specific purpose of making the Munsell hue, chroma and lightness scales perceptually uniform. Spacing in the widely used CIE L*a*b*system is based on the Munsell system. I was not considering systems such as the OSA-UCS that do not have an intrinsic hue scale, but Don is quite correct in pointing out that the OSA-UCS has improved uniformity (particularly in the spacing of chroma, I think).