An exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut features the on-location paintings that Frederic Church (1826-1900) did while traveling.

When Church ventured to the Old World in the late 1860s, he decided to visit Athens to paint the Parthenon, "the finest edifice on the finest site in the world."

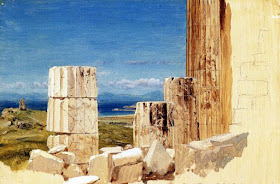

His studies are on paperboard, with thin, deftly applied semi-transparent layers of oil over a careful pencil drawing, resulting in an almost photographic level of capture.

Church's view of the Parthenon at night captures an unusual light effect at night. The curators say: "Notice the red glow illuminating the white marble of the Parthenon. It was a special day in Athens marking a visit by the Prince and Princess of Wales. The Greeks illuminated the temple with striking fire effects, and Church documented the rare event."

The main focus of his study was this view of the Parthenon, which presents the ancient monument as a noble ruin, surrounded by wild rubble. In fact, he would have had to screen out the bustling city of Athens that crowded many views of the site.

The structure itself had been almost perfectly intact until 1687, when a Venetian mortar shell hit the building and touched off gunpowder that was being stored there by the Ottoman Turks.

There's a handsome oversize catalog "Frederic Church: A Painter's Pilgrimage

James:

ReplyDeleteHow did those columns and lintels remain through all the natural & military disasters?

I'd found that the total foundation was a massive shock absorber. I'd cubed an apple whole, slipped into a bag, and fumbled my lunch. Upon impact there was barely a sound, and the apple remained intact. An engineering prof. explained that friction surfaces and room to flex dispersed the shock.

And the columns had been found to have fused, likely by pressure of weight and moisture acting on the crystalline lattice structure much as salt does during accretion. Plus, other column discs had been slightly roughened and turned together for the friction surface, making a match like two serrated mill files matched together. The bases were free-standing, but I suppose had been fit fused likewise.

Not being an archeologist or engineer myself, I'd like to know someday.

Thanks,

Tim

bollent@wwu.edu

I am curious as to the light source of the night painting. The red could be explained as setting sun but the internal illumination puzzles me as in 1869 the only lighting at the ruin would be natural.

ReplyDelete