For example, here are some concepts:

1. That thinking takes place in the brain.

But scientists are helping us to understand embodied cognition, which suggests that thinking is distributed throughout the body and shaped by our sensory experiences.

2. That consciousness only happens with complex nervous systems

But modern botanical science and studies of colonial insects suggests that emergent behaviors and structures appear beyond our current understanding of information processing.

3. That the mind and the body are separate.

But this Cartesian dualism has been challenged by various philosophical and scientific perspectives, including monism, which posits that the mind and body are intertwined and inseparable.

4. That we act on the basis of free will.

But many philosophers argue that free will is an illusion, and that our choices are influenced by factors like genetics, environment, past experiences, and even gut bacteria which shape our brain activity and behavior.

5. That we perceive the totality of the world around us.

But we’re only aware of a thin slice of the electromagnetic spectrum, and many animals and plants can sense things we’re blind to, such as ultraviolet light, magnetic fields, or vibrations in the air.

6. That time is linear and absolute.

But modern physics has shown that time is relative, flexible, and dependent on the observer's frame of reference. Some cultures also perceive time as cyclical or fluid.

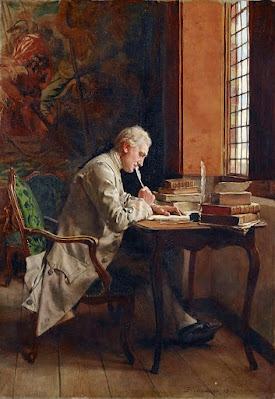

Read the rest for free on Substack Art: "A Poet" by Ernest Meissonier

RE: 4. The belief that we act on the basis of free will.

ReplyDeleteThe idea that we have no free will is one of the most pernicious viewpoints, because if someone fully accepts this premise (often in the name of ‘science’ or another external authority), they may begin to live as though they have no agency or ability to change. This naturally leads to a deterministic outlook, where all changes in oneself or others are seen as predestined by prior conditions. At its core, this belief strips away personal responsibility for good or evil actions, fostering the idea that 'bad people' don’t choose to act in evil ways and therefore should not be held accountable. On both personal and societal levels, this mentality breeds self-denial, depression, oppression, and a lack of compassion.

You may be familiar with William James, the American philosopher. In his youth, he faced a profound crisis. He wanted to be an artist, but his father’s emphatic disapproval left him with no room to pursue his passion. This led James into a deep depression, where he questioned the existence of free will altogether. Eventually, he came to a pivotal realization: “I can choose to think one thought rather than another.” He understood that free will wasn’t something bestowed upon him but something he had to assert for himself. His first act of free will was the decision to assume that free will existed and to think the thoughts he chose. This was the turning point that helped lift him from his depression.

If you accept the idea of free will, even as a working hypothesis—acting as though you do have free will despite outside authorities claiming it’s illusory—it can significantly expand the possibilities available to you. By rejecting the notion of a predetermined self, you free yourself from the limitations that come with that belief. Ironically, this stance is more scientifically healthy because it reflects an openness to testing theories through action to observe their results. This perspective encourages the development of skills and fosters a strong sense of self-worth. For an artist, the belief that artistic skill is predetermined (or a ‘God-given talent,’ an older version of the same deterministic thinking) undermines the very idea of self-improvement. But this applies broadly across all areas of life: accepting the complete authority of any external force—whether it’s science, God, or something else—can weaken your sense of agency.

Ultimately, you define yourself by the choices you make. This is the essence of self-determination: you take charge of your own decisions and direction. Through these choices, you shape who you are and continually improve as you make better and more thoughtful decisions.

The choice is yours!

Alex, Thanks for the thoughtful comment. I agree with you if you're saying that believing in free will is the only way to live a meaningful life. Beyond that, our legal institutions depend on the idea that each of us bears responsibilities for our actions. The arguments against free will come from people like Sam Harris and Robert Sapolsky, who cite studies that demonstrate unconscious brain activity preceding conscious decisions, which has been interpreted as evidence against free will.

ReplyDeleteThanks for your reply, James. I’m familiar with Sam Harris and others in the scientific community who promote this view, supposedly based on scientific evidence.

DeletePersonally, I find it concerning from both a psychological and societal perspective to live by these principles. The ideas themselves aren’t new—forms of predeterminism have been around for thousands of years. What’s particularly troubling is the appeal to scientific evidence to support these claims, as science is often regarded as infallible by modern thinkers. However, these studies don’t necessarily demonstrate the absence of free will but rather a lack of awareness of participants' internal decision-making processes.

Even though modern scientific experiments may be more advanced than, say, Prince Pāyāsi’s tests on criminals, scientists today are still mistaken in thinking that a phenomenological process—consciousness and mental events as experienced internally—can be captured and measured in purely physical terms.

Regarding the efficacy of human action, the scientific method can’t prove whether the scientists applying it are exercising free will in designing their experiments. Nor can it prove that their actions in creating and running experiments impact the results. The very process of scientific inquiry, including peer review, operates on the assumption of free will—after all, criticizing a poorly designed experiment would be meaningless if the scientists involved had no free will in their choices. Judging by appearances, the belief in free will and personal responsibility has been essential to the progress of scientific knowledge. But the scientific method itself can’t prove whether this apparent free will is real or merely an illusion. There’s also an irony here: many scientists assume that the phenomena they study follow strict deterministic laws, yet their method of inquiry presumes that they are not themselves bound by those same laws in the application of their work.

Both your comments align with my thinking and are better said than I could have! Especially the last part about method of inquiry which is part of what I was trying to say about the Sapolsky interview iny reply to kev's comment.Great post ,James!!

DeleteThere's also arguments provided of the idea of compatible free will with Daniel Dennet, including the neural basis argued via Peter Ulric Tse. So it's a semantic matter.

ReplyDeleteSuch a fascinating subject, though. 🛋️💭

Plenty of good reading stuff, Always nice to read you're blogs Gurney. 🛋️👍

1. A lot of people seem to do their thinking in other people's brains; speaking the problem aloud into the wind and then waiting for responses. We often collectively think, logical argumentation pinging from one sequential point in one brain to another in another.

ReplyDelete3. The mind affects the body, the body affects/acts on the environment. The environment affect the body, the body affects the mind. Thus each experiential realm or strata becomes (at least) an analogy of the others, in some sense. Hard to separate mind, body, and environment.

4. The more people seem internally fragmented; their instincts, subconscious or unconscious hopelessly disconnected from their hyper-symbolic conscious detective brain, the more they seem to believe they have no autonomy/free will. A lot of word/science/nerdy people seem to fall into this category. I think it is the hallmark of the artistic mind to be more in touch with the under-thinking within. Making us more apt to appreciate that all our levels of thought belong to us.

Hope you're doin' okay, Jim! ;)

"Under-thinking within" is a great description.In the interview I saw with Robert Sapolsky,he said that when he first formed his theory,as a teenager,that it was liberating precisely because it relieved him from guilt and anxiety...which I'm sure was unwarranted.Your phrase I believe relates to #2 about consciousness.If a person has to have a belief then mine is To me, it's logical that consciousness precedes existence.

Delete