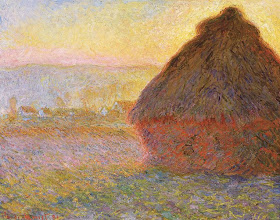

The first-glance impact is usually represented by an image with simple masses of color, painted with big brushstrokes without much detail, often with soft edges between the masses, such as this haystack painting by Monet.

Typically, “impressionist” images have high-chroma dabs of color that resolve into a larger blurry image. Recognizable small details are conspicuously left out.

We’re told that this is how the eye perceives on the first glance. Let me see if I can simulate this idea using a photographic image. Here’s an unaltered photo of a street scene.

Here’s an “impressionist” take on the same scene (using the Photoshop filter “paint daubs” and a heightened color saturation).

I believe there are some assumptions here that need examining. Does our first impression really look like an impressionist painting?

If I’m really honest about my own experience of vision, my first-glance take on a scene is nothing at all like a Monet. What I see in the first two or three seconds are a few extremely detailed but disconnected areas of focus. Small individual elements, such as a sign, a face, or a doorknob, take on particular importance immediately, perhaps because the left-brain decoding process (seeing in symbols) is so heavily engaged in the first few seconds.

I’ve altered the photo to try to simulate this experience by sharpening and heightening these disconnected elements. What happens in the first few seconds for you? I don’t know how other people see, because I’m stuck inside my own head. Perhaps eye-tracking and fMRI studies can help us to better understand what really happens cognitively in the first few second of visual perception. Maybe it varies widely from person to person.

What I’m questioning is not the artistic tradition of impressionism, but rather our habits of thinking about it. The idea of trying to capture the broad, simple masses of a scene is a valid artistic enterprise. But even though I’m a plein air painter with impressionist leanings, I believe that kind of seeing emerges only after sustained, conscious effort and training, or not at all.

Above: Sir Alfred East, “Night in the Cotswalds.”

Perceiving big shapes requires a deliberate act of defocusing or squinting. These are rather unnatural kinds of perception. When I squint and defocus on a subway, people look at me like I’m insane. Painting teachers know that students don’t see the big masses naturally. They need to be taught to do it.

(Incidentally, this big-mass mode of artistic seeing was very much a part of 19th century academic training, and was by no means exclusive to the Impressionists—but that’s another topic.)

I realize that the term “impressionism” was not coined by the artists, but rather by their critics. In any event the word and that sense of the word have become irrevocably associated with the movement. Of course the word has other definitions, such as the portrayal of transient effects of light and color, or a painting style using short brush strokes, and those meanings of the word are valid.

But the notion that impressionist paintings are accurate representations of our first visual impressions strikes me as false dogma. I’m skeptical of the word when it’s used in that sense.

“Impressionism,” whatever its merits as a mode of picture making, may not describe a universal experience of perception, so much as a particular style of painting.

----------

Related previous posts on GurneyJourney:

Eyetracking and Composition, part 1

Eyetracking and Composition, part 2

Eyetracking and Composition part 3

Introduction to eyetracking, link.

How perception of faces is coded differently, link.

The devil's in the details. I'll leave it at that as a first impression. I was trained from the age of four/five to see edges and shapes that just happened to be characters. I recognize characters right side up, upside down, backwards and forwards and how they relate to the space around them, be it light or dark.

ReplyDeletePerhaps the early training as a sign painter skewed my brain to the details and taught it to ignore the large masses of 'impression'. I don't 'like' Monet for that very reason.

My eye is instantly drawn to the light colored stone (probably the result of some repair) in the wall and tower things and to the people walking around. I didn't even notice the signs until you pointed them out!

ReplyDeleteTo me impressionism was always about focusing the painting on capturing the light and color usually with little effort put into detail or a tight finish. While that usually ends up with distinct brush strokes and large value and color masses I always thought that part was carefully planned and learned. To average a scene that well never came across as an accident or natural way of seeing to me.

ReplyDeleteExcellent, really insightful post. It exposes a vague, non-descriptive cliché of general art history which was in my opinion brought to existence as a combination of afterthought and misunderstanding. Impressionism got its name from the eponymous Monet's painting, but I very much doubt that he used the word "impression" in that title in its most immediate, physical sense, as in "visual imprint". I suppose the word relates rather to the mood the scene evokes.

ReplyDeleteIt is notable that some photographers are striving to capture the "first glance" quality, and the resulting aesthetic is strikingly different from an impressionist painting.

Some parts of art history/theory have become all too foggy and vague in the hands of some art historians who, not knowing much about actual painting, use a lot of terminology in a confusing or wrong way. I really appreciate articulate writings of real artists like Mr. Gurney on those subjects!

Impressionism is McCulture for women.

ReplyDeleteetc,etc ~ ain't that the truth.

ReplyDeleteIf you are 'honest' your first impression was that it was an outside daylight scene with buildings. After that, your eyes went to the details you described.

ReplyDeleteI doubt very much you looked at the stop sign then wondered if it was on a portrait or not.

Therefore the blurry picture without the details you show, would be more accurate to your FIRST impression.

I think I'm somewhat in between. I don't think I see something like the simulation of what you saw, at least not in this particular picture (I think it may be different when the composition has a more singular main point of focus), but rather something that's more like the impressionist take.

ReplyDeleteThe ideal impressionistic painting, to me, would be a cross between the blurriness of the impressionist simulation, but with decreasing "impressionistic-ness" on those focal points. Perhaps not all of them, but something that would make more sense focus-wise.

I don't quite like impressionism, but I'm not happy with some paintings that seem to have crispy detail all around. Somehow, it makes it lose realism and look more like a technical, almost diagram-like illustration.

That applies both to paintings and some special effects, specially visible on CG dinosaurs, mostly post-JP1, but JP1 excluded I guess. They often have a finely detailed texture that does not lose focus as expected by a real object that would be there where it was inserted. For that reason I find even some old stop-motion dinosaur movies (like the ones on that movie/documentary hosted by Christopher Reeve) better than the CG stuff we see in new documentaries or even movies. I think that if they just had some CG technique just to make up for the "missing FPS", make the animation smoother, it would beat 99% of the pure CG stuff.

My 'impression' when first looking at an image is all about contrast. So in this example, it's all on the right side of the image, first the sharp edge of the reflection in the foreground car window; next the windows against the yellow wall in the background. Everything else is just a dark mass, until I look again into the details.

ReplyDeleteGreat post!

True,the understanding of the way we see things have changed dramatically - as I actually learned on this blog or your books.

ReplyDeleteBut let's not forget that Monet had quite some problems with his vision.

I believe that some scientist or doctors have actually evaluated Monet's work and other artists work from a pathological point of view.

Put more simply: these doctors suspected abnormal vision with some artists, based on their work.

You are on the tip of an iceberg with this post. It's great that you're exploring the visual subjects and mentioning fMRI and eye-tracking at the same time. Neuroscience can help us improve many things including our system of government. Artist can be important message makers in conveying these extremely wide advancements in understanding. In order for people to accept and apply these advances they'll need us artists to give them something accessible, at-a-glance. Books like "How We Decide" by by Jonah Lehrer and "On Intelligence" by Jeff Hawkins have important concepts. To really stretch I would check out Chris Alexander's classic essay "A City is Not a Tree". I write a lot about the difference between information processing through a semi-lattice verses a hierarchy. I believe understanding how these two patterns interact will describe many things. Artists will likely do it best.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting thoughts!

ReplyDeleteMy eyes were attracted to the light bricks in the wall, then the signs and the green windows.

I only did pencil drawings for many years, so I learnt to squint my eyes to be able to see the light and shadows.

I think I read somewhere that the impressionists were influenced by oriental art. They had seen Sumi-e painting and that was how they started to paint with all the tiny strokes and dots.

Yes the influence of Japonism during that period is very important. I've always understood Impressionism to be about painting the light rather than the object. When Monet was working on one of his series paintings he would only work on a canvas until the light changed then he would switch to another canvas. It would take him multiple days of painting during a certain hour of the day to finish up a painting - and doing work back in the studio later was common as well. It was definitely not about a first glance.

ReplyDeleteGreat comments, everyone. Thanks for the links and leads.

ReplyDeleteI suppose this post raises other philosophical issues, such as whether it can or should be the purpose of a painter to try to capture his or her subjective visual experience. In a way, every painting becomes its own reality by virtue of the way it shapes the perceptions of the viewer.

Monet's motives are impossible to fathom, especially since he in particular resisted analyzing his own thinking too much.

It seems to me that art/science/thinking is like anything else and is a product of it's time.

ReplyDeleteThe notion of impressionism, that the eye records in the way the paintings (of Monet and others) show was probably, excuse my pun..., visionary at the time (and fashionable) and minus our modern technology as you mentioned with eye-tracking and fMRI studies. In fact maybe a better way of describing impressionism is it is a (another) way interpreting rather than the actual science of vision.

Science affects art and our way of thinking, art MIGHT even affect science and our way of thinking (sorry scientists).

As for how exactly do our eyes see, perceive and record a scene it is probably true that we all bring 'to the table' our own experiences as MrCachet states. Witness' to the same crime scene all report different 'truths' as lawyers very well know.

The different ways of 'seeing' as art is concerned may better fall into the category of interpretation. I don't necessarily see one way better than another, just different.

I had a drawing class where the instructor taught us that the eye can only focus on one point at a time, the rest is peripheral vision, hence the constant movement of our eyes to take everything in.

So which is truer, look at a scene for only 3 seconds. First, focus on only one point for that 3 seconds, describe what you saw. Next, spend that 3 seconds scanning the entire scene, describe what you saw.

You still only spent 3 seconds looking but probably have slightly different recollections.

So is a 'impressionistic', blurry image more accurate to our way of seeing or a highly detailed image more accurate to our way of seeing?

Maybe both and/or maybe neither. We'll see as science marches on.

Monet had serious eye problems, as did Manet, I've read. I think that also had a lot to do with the appearance of their work, especially their later work. I wonder how many other artists had eye issues that affected the way they painted.

ReplyDeleteI completely agree with your analysis here about perception and impression, and impressionism. It's interesting to see what you see first and that can be applied in a painting, would be a good experience.

ReplyDeletegreat blog btw!

I've been contemplating this exact area, and agree wholly. The Art History mantra always seems to misunderstand artists, as special, or different, ie Mutants.

ReplyDeleteFirst, Impressionists learned technical advances from new dye and textile methods, which produced strong visual effects previously underappreciated, if not entirely unknown. They also had new paints, with some new pigments, to try out.

The fact is, they did not "see differently"; they learned to look differently at the canvas. They pushed the limits to test what increasingly abstract jumbles and optical blends would still be perceived as whole scenes. An unanticipated, but pleasantly serendipitous side effect was the production of art which did not stagnate on the canvas, but often produced effects that never precisely settled down, vibrating and oscillating and challenging, anew, with each viewing.

The Art of the Impressionists was not about making accurate visual assessments of the observed scenes; it was about becoming sensitive to how the paint manipulations worked, and whether the result would pull the observer back in to an acceptable substitute for veracity, where detail was surrendered in favor of the visual stimulation. The scene was an excuse, a starting point; the work was about the paint.

I've been contemplating this exact area, and agree wholly. The Art History mantra always seems to misunderstand artists, as special, or different, ie Mutants.

ReplyDeleteFirst, Impressionists learned technical advances from new dye and textile methods, which produced strong visual effects previously underappreciated, if not entirely unknown. They also had new paints, with some new pigments, to try out.

The fact is, they did not "see differently"; they learned to look differently at the canvas. They pushed the limits to test what increasingly abstract jumbles and optical blends would still be perceived as whole scenes. An unanticipated, but pleasantly serendipitous side effect was the production of art which did not stagnate on the canvas, but often produced effects that never precisely settled down, vibrating and oscillating and challenging, anew, with each viewing.

The Art of the Impressionists was not about making accurate visual assessments of the observed scenes; it was about becoming sensitive to how the paint manipulations worked, and whether the result would pull the observer back in to an acceptable substitute for veracity, where detail was surrendered in favor of the visual stimulation. The scene was an excuse, a starting point; the work was about the paint.