A blog reader named Whiskey asked a question about line direction:

If we're drawing so that shading lines describe the contour and volume of an object, how should it be done? Should the lines go in the direction of the light source? Or along a perspective line?

I've attached a little jpg to illustrate my question because I'm not sure if I've made any sense. Which way is best for the lines to go?

Answer:

It's a good question. Actually there are no rules. Both ways you've suggested can describe the form well.

The one marked A is often called "shading along the form" or "along the axis." B is sometimes called "

bracelet shading" which I mentioned on another post. In that case, the lines (or brushstrokes, if you're painting) are going around the axis of the form.

On a larger compositional level, your choices often depend on the feeling you want to create.

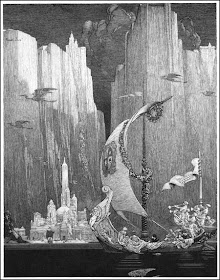

For example, in this fantastic world drawn by Franklin Booth, the lines on the far mountains are vertical, which reinforces the feeling of soaring majesty.

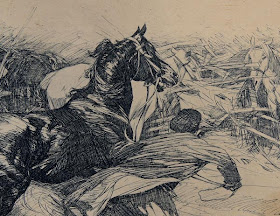

In this detail of a drawing by Polish artist

Stanislaw Bohusz-Siestrzencewicz (1869-1927), the lines on the horse's neck wrap around the cross section of the form, but he's also connecting diagonal movements from the horse to the man to suggest action.

In this drawing by the same artist, the lines spiral diagonally around the form to suggest the relaxed, informal posture of the woman.

So I'd say: experiment with both kinds of shading: along and across the axis. Also, try shading diagonally if you want to suggest atmosphere or action. Once you're comfortable with the choices, it will become automatic, and you can mix them up in the same drawing.

----

Thanks, Paul Mendonca for the Siestrzencewicz files.

More samples of

Stanislaw Bohusz-Siestrzencewicz

Andrew Loomis talks about a similar topic, stroke direction in painting, in his excellent book

Creative Illustration

, which has just been republished.

"I have noticed that when I paint outside I nearly always return with a less than bright painting. It will look good in the field but then look disappointingly desaturated in the studio. I assume this is because the pupils are so dilated outside and letting in so much light that when I'm back in the studio and my pupils are normal again and the light bouncing off the paint is considerably reduced (thus reducing chroma). I've thought I could make a kind of blinker out of black tubes to restrict the amount of light entering my eyes except in the foveal area. But due to my bifocals I doubt I could get such a gizmo to work. Obviously one could try and overcompensate for this effect by adding high chroma pigment but this seems untrue to the plein air idea. Have you run across any solutions to this problem?"

"I have noticed that when I paint outside I nearly always return with a less than bright painting. It will look good in the field but then look disappointingly desaturated in the studio. I assume this is because the pupils are so dilated outside and letting in so much light that when I'm back in the studio and my pupils are normal again and the light bouncing off the paint is considerably reduced (thus reducing chroma). I've thought I could make a kind of blinker out of black tubes to restrict the amount of light entering my eyes except in the foveal area. But due to my bifocals I doubt I could get such a gizmo to work. Obviously one could try and overcompensate for this effect by adding high chroma pigment but this seems untrue to the plein air idea. Have you run across any solutions to this problem?"

.jpeg)