Can you enter a painting that uses gouache into the annual competitions of the various watercolor societies? What are their rules about mixed media?

The

American Watercolor Society rules allow "water soluble media: watercolor, acrylic, casein, gouache and egg tempera on paper. Watercolor board is not accepted," but forbid "collage, pastels, class work, copies, digital images or prints."

The

bylaws of the

National Watercolor Society don't mention gouache specifically, but they define watercolor fairly broadly to include "aquamedia, watercolor, acrylic and other watersoluble

media," specifically excluding work in encaustic or oil. The latest

exhibition prospectus puts it this way: "Painting must be watermedia paintings on natural or

synthetic paper Yupo, Aquabord and Clayboard. No stretched

canvas or canvas board. Collage may be used but aqueous

medium must constitute 80% or more of the work." They forbid digital media and photography, which presumably means that generative AI is not acceptable.

I asked Lana Cease, who is on the board of directors of the

National Watercolor Society to explain. "The main difference between the societies that you mention," she says, "are mainly the media that they allow. Of course, anyone could be a member but to enter the exhibitions you have to use your materials in a certain way."

Lana says that the NWS "welcomes everyone in any media with all skill levels. We have members that just started painting recently, and also have members that are highly trained, awarded and successful. We do allow art such as collage if the collage is mainly water media, but we don't do mixed media like oils and acrylics together. You could mix anything water based. So essentially, you could use watercolor, gouache, watercolor pencils, water soluble pencils (although we allow pencil as long as it's not predominantly pencil), watercolor markers, and fountain pens if they contained water based media.... and still be considered water media with the look of mixed media. We can't allow things like pastel or oil based paints in our exhibitions, but of course, we still would love to have those types of artists be part of our organization. We're very inclusive and we try to be progressive."

The TWSA goes on to exclude the following:

• Opaque white paint, of any kind, such at titanium white, Chinese

white, etc.

• Gesso, matte medium, or any other priming material or exterior

surface treatment

• Gouache, acrylics, or water-soluble oils

- Inks, metallic, or iridescent paint or products that leave a metallic,

graphite, or reflective sheen.

• Watercolor crayon, colored pencil, charcoal, pastel, Conte sticks, or

Conte Crayons

• Varnish, wax, wax crayon, oil sticks, or oil pastel

• Collage or surface constructions, impasto, embossing

• Watercolor resist, such as Frisket, that is not completely removed

from the final painting

• Yupo or similar papers.

• Canvas or canvas paper

• Use of digital images or enhancements printed on the paper.

What is the rationale given by the TWSA for excluding gouache when so many pigments classed as watercolor (such as cadmium yellow) are more opaque than other pigments (such as diazo yellow) that may be in a tube of gouache?

In their FAQ, the TWSA addresses this issue: "The use of transparent watercolor paint includes pigments classified as 'opaque', such as the cadmiums and others which are acceptable as long as they are applied largely in a transparent manner. The focus on the way paint is applied to the paper, 'in a transparent manner', is to allow the white paper to create luminosity rather than, 'in an opaque manner', which obscures the reflected light. This shifts the emphasis from a discussion of pigment to the way in which pigment is applied. In practical terms, if the texture of the paper can be seen through a dark area of the painting, or there is an undulation of value or color(s) within it, then it is not 'opaque'."

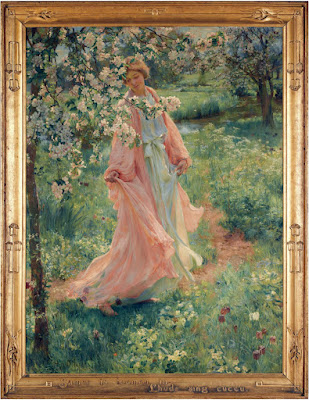

What is the reason for banning opaque media and so many other techniques, especially given the fact that many traditional masters of watercolor, such as John Singer Sargent, Winslow Homer, and William Trost Richards frequently used gouache?

In a single word, the answer would be luminosity. As the NWSA argues on their website:

"'The white paper showing through a transparent wash is the closest approximation to light in all the media, and light is the loveliest thing that exists.' This is how Edgar Whitney describes and extols the virtues of transparency. Cheng Khee Chee expands on Whitney's definition by describing the effects of transparent washes. 'The flow of washes possess a strong evocative power. The interpenetration of colors creates mysterious precipitations and nuances.' Respected artist and teacher, Frank Webb, describes luminosity as '...the painting's ability to give off light. It generally derives from the light within and beneath - such as the white of watercolor paper under paint.'”

I'm sympathetic to these reasons for using transparent pigments, because transparent passages can lend themselves to efficiently achieving certain kinds of gradients and textures that are hard to execute with opaque paints.

But in my experience, transparency offers neither a guarantee of luminosity, nor a hedge against muddiness, since those qualities have more to do with the disposition of tones within a picture, however they are achieved technically. Flat, opaque, or thickly painted passages, if they are of the right value, can sometimes bring light and air to a picture.

My own preference with water media is to begin a picture transparently and bring in opaques or other mixed media wherever they're called for, and most often my own paintings in water media are a blend of opaque and transparent passages, just as they would be if I were painting in oil.