One of the principal instructors, Fernando Freitas, recently took me through the building to explain the course of study.

The curriculum is based on the book by Charles Bargue and Jean Leon Gerome, which was originally produced in the mid-nineteenth century for the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris.

There is no portfolio entrance requirement. Students come from all different backgrounds and ages. Each student follows the same series of steps or levels. They move ahead to the next step whenever they’re ready.

The first skill to master is to reproduce a two-dimensional drawing. The goal is to learn to capture shapes and to understand the division of light and shadow.

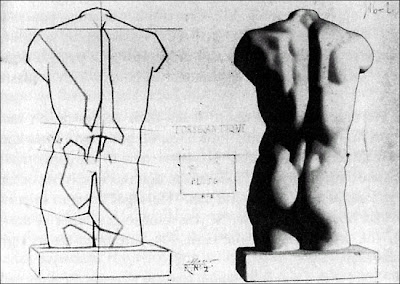

The first skill to master is to reproduce a two-dimensional drawing. The goal is to learn to capture shapes and to understand the division of light and shadow.The next stage is a vine charcoal or carbon pencil study to understand the effect of light and shade on a plaster cast. The drawing and the cast are set up side by side in the same light and checked until they match perfectly.

This so-called “sight size method” takes a lot of floor space because you have to back up from the subject and see the drawing and the model in one view. Two students generally work side by side from the same cast.

This so-called “sight size method” takes a lot of floor space because you have to back up from the subject and see the drawing and the model in one view. Two students generally work side by side from the same cast. They then move to painted studies of casts, still life studies, and painted studies from the nude model. Some studies can take 30 to 60 hours of work.

Mr. Freitas also encourages students to learn from the classic texts on drawing and painting by Harold Speed. He has produced an instructional DVD called Drawing the Figure, which follows the process of creating a tonal drawing of a standing figure from start to finish.

“We’re more an academy than an atelier,” Mr. Freitas said, “because we are based on an objective, classical approach rather than the working methods of one individual master.”

The atmosphere of the school is focused, energetic, and collaborative, more like a martial arts academy than a free-form art school. It feels like entering the dojo with a clear mind, focused on the task at hand, leaving behind your worldly concerns. One easel was emblazoned with a sign “I SEEK EXCELLENCE.”

The atmosphere of the school is focused, energetic, and collaborative, more like a martial arts academy than a free-form art school. It feels like entering the dojo with a clear mind, focused on the task at hand, leaving behind your worldly concerns. One easel was emblazoned with a sign “I SEEK EXCELLENCE.” The way of learning art at ARA is very different from other schools, and I know that not everyone agrees with it. I’ve heard the criticism that the sight-size academic method it leads to uniform results, or that it amounts to passive copying.

I think those views misunderstand the objectives of classical training. The purpose is not to teach style or personal expression, but rather to give each growing artist a solid foundation to build on, and to offer them a deep familiarity with classical models and timeless standards. Drawing and painting at that level of sensitivity is a very active process indeed. It deeply engages every fiber of a student’s being.

The ARA is not trying to be everything to everyone, and I believe that is their strength. The results that are framed up in the hallway are nothing short of breathtaking, and the sense of shared purpose among the students is palpable.

There is much every art school can learn from the example of the ARA. I believe that every art student should have the chance to go far beyond the 20 or 30 minute poses that are common in many art schools and to see how finely they can tune their response to the visual world.

------

Official Website for the Toronto school (with a new campus just opened in Boston, MA), link.

Freitas video on drawing the figure, link.

Bargue book on Amazon, link.

More about the sight size method, link.

33 comments:

Whenever I read or hear something about a school that follows the classical tradition, I'm always torn. Personally, I see the immense benefit of this approach, it's like life drawing on steroids. On the other hand, and this is something I've never heard anyone bring up, what happens after all this form of training is done? Do the students learn how to construct imaginary figures or composition? I could care less on the fact about the criticism regarding uniformed results, since it's clearly not geared towards that, but I always wonder if they ever teach anything else beyond this.

Drew, it's a great question. I just read a quote from the American illustration teacher Howard Pyle, who taught imaginative work to students who had gone through this academic training:

"The hardest thing for a student to do after leaving an art school," he wrote, "is to adapt the knowledge there gained to practical use--to do creative work, for the work in school is imitative...When I left art school, I discovered, like many others, that I could not easily train myself to creative work, which was the only practical way of earning a livelihood in art."

It's a problem that is also addressed by Harold Speed, who believes students should always flex their imaginative muscles besides the academic studies. I don't have the fitting quote at hand though :).

In a direct response to Drew's question: From what I've heard from students I don't believe they actually teach other things at these schools.

I really with they would include longer poses into the usual art school curricula, because as important as gesture drawings may be it can become really frustrating to never have time for closer observation. (Poeple at life drawing sessions I've attended never quite seemed to understand the request for, say, half an hour poses.)

The ARA is unabashedly focused on drawing from a model, but texts like Andrew Loomis's books are often referenced for those who want to learn to draw imaginatively. Also, I think once one draws enough form life, they gain a visual library that they can call upon when necessary.

I think really long poses are especially good for those who want to draw the figure without a model because you have the time to really analyze the body. With short poses, there just isn't time to study the model, apart from the gesture (which is useful if you are interested in less realistic forms of art like Disney-style animation).

A good exercise I did when I was at the ARA was try to draw the model from memory after class. Although my sketches were not nearly as specific as my drawing from life, I was really surprised at how much I could recall in terms of the anatomical detail and shadow shapes.

I went through a more traditional, "modern" art program. I had some really wonderful teachers but we never even considered going into something as deeply as the ARA is. I really wish we had. I find myself trying to learn how to paint all over again after being out of school for many years.

Your comparison to a martial arts school is interesting and something I can really relate to. I've been practicing Shotokan Karate for 30 years with a very traditional group. The practices are extremely rigorous and we practice the same things over and over again. Eventually the techniques become so ingrained that they just start to happen in a very natural way. Karate is something that can't be learned by talking. It has to be learned with the body. When you see two opponents who have trained for a long time with the right mentality face each other it is electrifying.

I think that with all things our individuality and creativity eventually emerge and strong, directed practice can only enhance that.

Thanks again for the great posts!

All these comments are very valuable and recognizable.

But I have doubts about building up a 'visual library' by painstakingly copying what you see.

I fear that with this approach, one might tend to 'flatten' what you see before bringing it to paper. That's why I like the idea of one of the previous posts, where an object has to be reduced to flat planes. This way you are forced to think of your subject as a (simplified) 3D object. I'm sure that this way you are really building a 3D library in your head, which will allow you to imagine the same object from a different angle later on.

Erik, if this technique is anything like what I saw a few professors teach back at my old school, then I think I can agree with you on it not developing a visual library in regards to being able to construct a figure from imagination later. These drawings are usually gridded out and the lines are found through weird (at least to me) mathematical procedures, all to aid in the sight drawing.

I'm actually surprised to hear a lot of people saying their school didn't do longer poses, or that's not the norm at least. I guess I was fortunate the professors I studied under usually did half-hour poses in conjunction with 1-5 minute ones.

I love the philosophy of the Charles Bargue system: mastery of work from a 2-D reference, and then moving on to mastery of work from a 3-D reference, etc.

As an art major as a college freshman, I was insulted when on the first day my professor, Leon Parson, laughed at us saying, "Why do you want to paint, when you don't even know how to draw?" He then assigned us to copy every drawing from the Bridgman and Vanderpoel books on our own time, and while in class we worked from the live model. The poses varied from a couple of minutes, to longer ones of 30 minutes, sometimes longer.

When the semester was over, I agreed with his first-day assessment of our skills -- I really did not know how to draw or to observe. I was no master at that point, to be sure, but I had made incredible progress.

James, so glad I got to see you speak at the Academy of Realism in TO. I found it very inspiring to hear how you developed the Dinotopia idea. I like your no nonsense approach to art too.

cheers, Michael

(and thanks for signing my book!)

I agree with Craig. I feel that I was asked to be creative and original without the necessary foundation. I think every art school could learn something from this school. With the tools the students pick up, they would understand light and form and be able to apply them to observation of forms from life and creative compositions.

There are actually some other thoughts on this type of teaching. Many of the 'classical' ateliers teach sight size. Most of those that stem from R.H. Ives Gammell are very much of this thought. My teacher, also a Gammell student, while trying to pass on much of the vast amount of knowledge he gained from Gammell, does not have students work sight size but teaches drawing in a relational manner (comparative measurements). The set up is the same, but the artist fixes his overall boundaries on the paper or canvas (basically top and bottom of the subject)and then everything else relates to the 'big'. It is more of an intuitive way of working, and having tried the sight size myself, I found working relationally to be much more enjoyable. Sight size feels like mechanical work to me. Mr. Ingbretson refers to sight size as nothing more than a place on the floor. Once you start, nothing can move, you are limited to a particular lighting, and very large subjects would be hard to complete this way. Working relationally one can move the easel, work in odd lighting situations, and is not so constrained to perfect conditions. I also think it trains the memory a bit more. I have not been able to find the quote, but Degas mentioned someone working sight size, discounting this method saying 'painting is about relationships (of -proportion, values, colors, edges, and temperatures)'.

Both have their pros and cons, and studying either is a great way to 'learn to see'.

The Bargue book actually discusses these two ways of working.

When asking what a student does after this training, the answer is simple- he keeps doing it. Once you have this training, I think it gives the student great power to be able to represent in paint, anything before him. Much like the Bonnat quote when explaining painting, "Make it as like as you can, then make it more like."

As a student out of this sort of training, you know your job.

Frank Mason would tell his students to do both. Study classically but also too learn how to compose and work out of your head. He was not found of the French academic tradition and was more interested in how Titian and the Venetian school worked. Rubens and so on. However we had plaster casts in the studio, we did not spend 30 to 40 hours on one drawing them though.

I see the benefit of doing this kind of study for two to three years depending on on how well one advances. I'm not sure why they don't have a year of doing nothing but painting compositions. I mean it could be done. You can get models, props,develop an idea based on a myth or historic event. Or a story like Moby Dick.

Richard-

I totally agree with your view on sight size; it's a very useful tool, but it's also very limited. That's something I like about the ARA; the casts are done sight size, but drawing from the figure is done with comparative measurement, and the Bargue's are done with both.

Erik

I don't think there's anything to fear from "flattening" the subject before committing it to paper or canvas: I believe it's exponentially easier to draw something accurately by imagining it as a flat shape rather than trying to capture it as a three-dimensional object. When you have the shapes secure, then you start thinking of volumes and planes.

Seeing flat shapes/contour and seeing form aren't mutually exclusive, I think the best draftsmen do both. You're totally right that being able to imagine the basic forms is crucial if you want to be able to draw something from any angle, but the contour helps to place those shapes in relation to each other and should be considered when composing your picture for maximum effect (think about the "shape-welding" that Mr. Gurney has posted on).

jeff

I think it would be awesome if some school would combine academic technical training, with the compositional/imaginitive side that university/art school illustration programs provide. There are a few schools out there that try to do this, but it always seems like compromises are made and one side gets short-changed in favor of the other. I guess the best thing to do if you have the time and money is to go through both types of training in their entirety.

Jim,

It was so great to get to talk with you last night. Thanks for all the encouraging words!

The lecture was fantastic and so enlightening.

If I'm not mistaken the ARA is an off shot of John Angel's school or it was started by him I believe.

This painter Luca Battini was a student of John Angel's and he is painting a huge mural. It is just what we are talking about, the artist is using all his powers to create something great.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7558492.stm

I forgot to add it's a 1,700 sq ft Renaissance style fresco that will tell the story of Ranierus, Pisa's patron saint.

Jeff

Thanks for that link! What Mr. Battini is doing is astounding! I can't believe he's working in true fresco on such a large scale. The video was really cool, too. Some will undoubtedly call the work old fashioned, but I think it's awesome.

Also, the ARA was indeed founded by Mr. Angel.

somthing about this seems so mechanical and passionateless? i dont see the fun in this, the enjoyment?

the phrase engraved in the easel " i seek excellence"? i guess with what i like to do with art i would say "i seek enjoyment".

why some people find so much joy in saying they spent 50 hours on somthing i wont understand. i would rather be able to say i spent 8 hours on somthing and loved almost every minute of it. then say i spent 60 hours on somthing and thank god its finally done, haha.

that being said, i would proably say that the artists i love the most proably spend 60 hours on one painting and love every minute of it, so much so that they lose track of time enough to not know how long it actually took.

i would think making art a labor of love would produce better results then having a labor of excellence?

Eric

The work is definitely mechanical, but the goal isn't to create a work of art (at least not immediately). These are all just learning exercises that, hopefully, will teach one some of the skills that can be used to create something more passion-inducing and imaginative.

For me, the fun and enjoyment in these kinds of academic exercises comes from learning and having those "aha!" moments. I find myself freezing up and getting overly tentative when I make the mistake of thinking that I'm creating some artistic masterpiece.

The academic way certainly isn't the only way to learn how to become an artist, and it isn't for everyone, but I'm thankful that this type of training is even still available today.

Eric, I don't think it's so much about producing the art as a work of love, and instead more about striving to achieve technical acuity. I can see reasoning: You go to school to hone and refine your fundamentals and your skills, not to be let loose and draw whatever you want. That's what life after is for.

I was already a working illustrator when I bumped into a sight-sized program/atelier. The first few night classes were a bit tedious, but after the proportions and the X/Y coordinates were plotted, it then allowed an amazing opportunity to study the physics of light, how it glares, bounces and softens. You can't lie about your drawing when it is next to the cast for all to see. One night the lead instructor, Pat Jerde (some sort of Gammell relation), took me around the school and pointed out light, shadow and line effects on some of the permanent art collection pieces. I learned more in that night than in all of my undergraduate drawing classes. I was a medical illustrator with a staff of 6 at the time and they also noticed some good benefits in my day to day work. I'm really happy I learned about sight-size and "sight-tone" method.

Eric, I have to disagree with you.

The work is not mechanical. It depends on who does it, how they deal with the subject and material.

These studies are about developing chops. Like a musician who practices scales 10 hours a day.

the idea is to get good enough so that when you have to deal with that Bach or Mozart credenza, you don't' have to think about the notes. You think about the art, the passion, the story and the emotions.

You might think what a waste of time. This kind of art education might not be for you, which is fine. However for centuries this is how it was done. How do you think Rembrandt, Titian, Rubens, Sargent and Bouguereau learned became the great artist we now admire. By doing this kind of study in some form. Of course these artist had exceptional talent to become the giants we now admire.

I will say this it can't hurt having this kind of training. What one does with after the fact is based on talent and vision. As Luca Battini I think has in spades.

Drew said (in the very first post): what happens after all this form of training is done? Do the students learn how to construct imaginary figures or composition?

Because the one time I tried to apply for Art School (nearly 30 years ago) I was rebuffed because my art was 'too realistic' and this was immediately equated with 'chocolate box kitsch', I feel rather strongly about this insistence that 'being creative' aka 'being Yourself' is somehow the Be All and End All of Art.

Allow me to make a metaphore. Right now I'm writing my thesis, and since I'm more of a visial person I can tell you that writing is HARD. Why? Everybody who knows their ABC can write, can't they? So why would writing a thesis or an essay or a novel be so difficult. It's not the creative bit, I can tell you that. Anybody who willingly takes up a pen has already creative down pat. What's difficult is the writing itself. First of all, writing has RULES. Rules of grammar. Rules of form. Rules of logic. If you do not know these rules, and practice with them, anything your creativeness will try to create will fall down flat. (as this comment will show since English isn't my native language and anyone better versed in English could make a better job of this)

Now, if the Realistic Art Acadamy was a writing discipline, I'd say it would be Translation. The students try to 'translate' an object to a different plain as accurately as possible.

Now, I did a bit of translation last week as a favour to a friend, and let me tell you, it was HARD. With translation you have to be really INSIDE language, to find the exact right shade to convey a certain word, its obvious meaning and the right shades of sub-texual meaning, and all done as elegantly as possible. The most important thing however was that it wasn't about ME. It wasn't about me being creative. It was about the piece, it was about the glory of language, it was about the creativity of someone else whose creativity I had to render as accurately as possible, but it wasn't about ME. And this was a Good Thing.

Any artist, visual or textual, would profit from this exercise. Maybe I'm showing my age, but I've always found this post-war insistence that it's All About the Individual and his Creativity rather baffling. How can you create great art when You are always in the way? By putting the subject, the technique, the tools, the materials and above all the accuracy first, these students will free themselves of the pressures of competiteveness and ego and any human being would benefit from a spot of that.

Personally, I don't think any of these students would have a problem 'being creative'. I've never heard of anybody complaining that their mastery of technique somehow killed their creativeness (don't get me started about the CoBra Group and their 'spontaneity' and 'inspiration from children's drawings'! This comment is far too long anyway)

"I'm not sure why they don't have a year of doing nothing but painting compositions."

That sounds like it would be so much fun!

As a writer, the best course I took in grad school was "Sentence Power," taught by a poet. It was a laborious class where we dissected the sentences of famous writers down to their fundamental parts, then rebuilt the sentences from this exact grammatical architecture, only using our own words. We never moved beyond the sentence level. Only by first consciously "worrying over" the placement of each word can you hope to achieve control of your writing. Everything else is an accident. It's commonly iterated that Joyce spent entire afternoons on a single sentence.

Only I'm not sure if the same applies to drawing and painting.

That sounds like an amazing school indeed. I think many artists could benefit greatly from having such training, I know as a realist myself, I would absolutely love to undergo such challenging work. To use those skills learned and apply them to our own expressions and imaginations would put you leaps and bounds ahead of the ones who consider it to be "wasteful".

It's not about "copying," it's just another tool learned to add to our bundle of tricks and skills which an be brought forth to create even more convincing images. It's better to have those skills attained and choose when to ignore them instead of not having them in your toolbelt at all.

I am just going to throw a few thoughts out here. I think Eric’s idea of art as a labor of love is right on, it is the only thing that can sustain you, otherwise the labor just becomes drudgery (As Einstein said “true art is characterized by an irresistible urge in the creative artist”) and I have to disagree with Jeff. I think Jeff is right you have to master your craft but your craft comes from some conviction of what you think constitutes reality, not by endless copying nature. Of the artist Jeff mentioned, Rubens, Remabrandt, Titan even Sargent (Bougereau being the exception) I have never seen a drawing by their hand (except the young Sargent) that looks like an academic drawing. Titan's drawing is as far from academic as imaginable, what few drawings there are by his hand. Even the French academy drawings of Boucher look nothing like academy drawing from the 19th century. Nor Gericaults

These artist thought in the round, mass preceded everything. And that is why I really have to disagree with Erik’s comment that shape precedes the form or the mass or that you can get the mass from drawing flat contour shapes. Of the above mentioned artists all their shapes where a product of their mass conceptions and that is what makes their work so powerful, the completeness of their conception of things allowed them too relate many relations at once. This is also what makes it so hard to mimic them as the mental effort can be quite daunting and humbling. How do you know where to place your planes, light and shade and line work until the mass is conceived, otherwise you are just kind of copying?

That is the problem I have with the Betty Edwards method, copying reduces and neglects aesthetic thinking. If the light is perfect and you have a great work of art to copy you could go years without even considering anything aesthetic such as balance, pattern, weight, orientation, movement, depth etc (believe me I know). these things are what the artist brings to reality. As Bridgeman says the artists senses there is more to the figure then what meets the eye.

And Delacroix said if a man falls from a fourth story window you should have him drawn before he hits the ground. And according to Vernon Blake in 19th century France the test for admission into the academy was a short drawing. As one can tell the students ability to comprehend the essence of the figure in a few moments time. And a final quote from Poussin a true classist’s “It is through the observation rather than the copying of nature that a painter develops his skills.”

Rubens was found of saying that all students should master the antique.

What he meant by this is the study of casts and Greek and Roman statues.

The way a lot of 19th century academic drawings look is not the issue. The issue is learning to draw well. How one learns to do this is up to them. I did not learn to draw in the French academic tradition. I was taught to study anatomy, look for the massed forms, rhythm, balence, all of which is in the Bridgman books which I used, still do.

However I think doing a few perception based drawings or paintings is very good for the training the eye. If you think all forms are rounded I have to say look again. I'm studying drawing now with a student of Ted Seth Jacobs who uses the block in to establish the forms. I think this idea works. It makes sense and it helps to find the rounded forms.

The problem is most people draw rounded forms that are not on the figure. Careful observation is the only way to overcome preconceptions of what you think the figure is.

The idea that one has to love what they do to do it seems misplaced to me as well. It would seem to me that if one is choosing to become an artist that one had should love doing it.

I saw their figure drawing video.

Some people I know ragged on it, but I thought it was okay.

Sorry Jeff, lots of the time I am just feeling out my own ideas about art and this blog is an awesome place to do it.

What I meant by in the round was thinking in three dimensions, the planes of course can either be round or flat or a combination that is up to the artist.

I have heard that Rubens statement before. Could he not be saying by studying the antique one develops clear ways of thinking about nature? Or clear ways to order to nature? What is so powerful about Greek culture is the objective way they thought about nature and this thought is what produced their art, to me this is what Rubens is saying.

Doesn’t how a drawing looks reflect how a drawing is thought? Isn’t an artist presenting us with a certain viewpoint or outlook of how things are order? Don’t we use our subjects not only to experience the rhythm and delight of nature but to give objective existence to our feelings about nature? Why is Matisse so popular? It is not because he is correct but because his work is so delightful, his painting and drawings give praise to nature and people know it.

The form or lack of form can be felt in a drawing, and this is also what I meant by how a drawing looks, the more powerful the masses are conceived the more the artist can dance his chalk or brush in any direction in space or on any surface he chooses. The succinct simple statement is always the most powerful. But of course you are right there is an immeasurable amount of hard work involved in developing the skills to truly draw well, and drawing from life immeasurable improves your powers of observation.

What I meant by loving what one is doing I guess is feeling the need to express something or say something about the forms of the world. To me the quickest way to some success is truly understanding how the things of the world work, which is why I like this blog so much, James is always explaining principals

Here is another painter, Conor Walton he's from Ireland and he studied with Charles Cecil.

He is classically trained but he is also very inventive.

http://www.conorwalton.com/index.htm

Tom I'm sure there is some of that but I think as do a lot of more learned people who know more than I do about this subject, that Rubens was talking about studying casts and sculptures as a way of learning how to draw. That is they would do this before moving on to the figure.

this kind of blog always useful for blog readers, it helps people during research. your post is one of the same for blog readers.

Post a Comment