|

| Ilya Repin's portrait of Stasov |

|

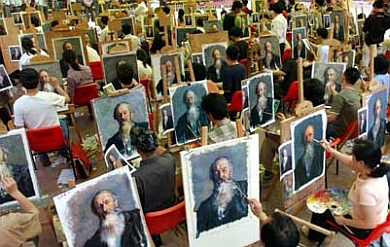

Photo of the copying room at the Da Fen Oil Painting Village in Buji, Longgang, Shenzhen, China, which employs over 5,000 artists. |

Hi, Bob,

It's an interesting problem, though not a new one, except perhaps in the scale of the enterprises. I like to come at the issue from a lot of different angles:

Copying a master's work was and still is one of the best ways to learn. Here are some of the copies I did when I was teaching myself to paint. They include postcard-sized copies Rockwell, Bouguereau, Waterhouse, Moran, Cornwell, and even that same Repin painting of Stasov.

Many art students do copies at the same size of the original, matching it as closely as they can. Not surprisingly, the market for historical paintings is filled not only with forgeries but also with copies made as legitimate learning exercises, though they should be labeled as such to avoid confusion.

Many art students do copies at the same size of the original, matching it as closely as they can. Not surprisingly, the market for historical paintings is filled not only with forgeries but also with copies made as legitimate learning exercises, though they should be labeled as such to avoid confusion.

|

| "Young Girl Defending Herself from Eros," both by Bouguereau |

Many academic artists made replica copies of their own works and didn't consider anything wrong with having multiple originals. For example, Bouguereau painted more than one original oil painting of "Young Girl Defending Herself from Eros."

From a philosophical perspective, all images are real in a way and unreal in a way, too— and all copies are varying degrees of "faithful," "mechanical," "genuine," whether they're made by humans or machines, or some combination.

From the customer's point of view, as long as you know what you're buying, I suppose no one is hurt by copies. As long as some people merely want a hand-painted image to hang on their walls and they don't really care about who painted it, a market will rise to meet that demand, just as there has always been a market for reproduction antiques.

From the creator's point of view, some artists regard copies as flattering and some as potentially infringing. That mainly depends on whether it's for sale and whether the attribution is genuine. American crafts artists have long been fighting Chinese knockoffs that undercut their market by matching their work exactly but for a much lower price. NPR did a report about New England crafts people fighting such a lawsuit.

Sometimes a copy can sell for more than the original, such as Glenn Brown's copy of a Chris Foss spaceship painting, which sold for 5.7 million dollars, while Foss's painting sold for only a few hundred. The legal and moral argument in that case is whether the recontextualization—the larger size, the new title — legitimized the work as a transformative new work. Whether such a high profile copy diminishes or enhances the work of the "real" original is a matter that's open for some debate.

|

| Bob Dylan's "Opium," (2009) next to a photograph by Léon Busy, taken in Vietnam in 1915/ Left: Gagosian Gallery / Right: © Musée Albert Kahn, courtesy HuffPost |

Other high profile artists have gotten in hot water for copying. Singer-turned-painter Bob Dylan received some adverse publicity a while ago when his "Asia Series" of paintings at the Gagosian gallery, which purported to be taken from his direct experience of his travels, turned out to be copies of historical, and sometimes copyrighted photographs.

Copying has its place in art, especially as a learning exercise. But originality and authenticity can be a rare commodities, even among so-called creative geniuses. The best thing is to be open and honest with what you're doing, and give credit where credit is due.

27 comments:

Thanks for this post, James. It's a matter worthy of discussion that begs for the sort of clarification you provide here. As someone who has enjoyed copying masterworks (though I do that much less these days), I agree that any that are sold or given should be properly identified as copies and labeled as such. But I've always wondered about the best way to do that labeling. It seems that it really must, for aesthetic reasons, be done on the back of the picture, as permanently as possible. I have tended to do mine on canvas, mounted on board, so the back of the painting is, theoretically, possible to change/remove. What are your thoughts on the best (ethically and relatively permanently) way to label copies?

I've considered this problem myself. I would love to hang a copy of Van Gogh's Starlight on the Rhone or one of Monet's haystack paintings. For this, I would need to go the copy route because I haven't won the lottery yet. I see no problem with a copy of a long dead master as long as everyone involved knows it's a copy. As for copying works of living artists, I would stay as far away from those as possible. Unless the artist has given you permission to go ahead and make copies of their works, it is highly unethical in my view.

That being said, I myself, am getting ready to do a copy. I want to do a painting of one of Rembrandt's self portraits. He's been dead long enough I shouldn't have any copyright issues. I also intend to change the size so that no one will mistake it for the original. Of course, holding the two paintings up next to each other I'm sure it will be easy to pick the original and the copy. Unless Rembrandt comes down and takes over my arthritic old hands and guides them. I'm not holding my breath.

There is an excellent book on the subject "Draw; How to master the art" by Jeffery Camp with the inro by David Hockney no less. This is what Hockney has to say" Copying is a first-rate way to learn to look because it is looking through somebody else's eyes, at the way that person saw something and ordered it around the paper. In copying you are copying the way people made their marks, the way they felt, and it has been confirmed as a very good way to learn by the amount of copying that wonderful artists have done"

Many wonderful drawings and suggestion through the book.

This topic is very timely!

recently completed a grisaille that I went over thin oil washes. I made the mistake of going too dark in the grisaille and painting subsequently turned out very dark when I applied the washes. I am getting ready to start again today on the same motif, this time painting it in the usual manner I normally paint. Would both be considered original works of art?

I had no idea that artists made copies of their own works.

For at least a decade, I've considered making small "limited edition originals" of my own design and selling them online for less than my one-of-a-kind larger paintings.

They'll save me time, as I'll only need to design the work once, they'll be affordable, easy to ship... But each will be entirely painted by me, the artist... Rather than having reproductions made, which can get costly.

I don't mind repeating myself, and I imagine that each iteration will get better.

Lori raises an interesting aspect of this topic. If an artist creates duplicates of her own work - identical in subject, style (and, let's say size too), is she obligated to disclose that to a buyer who isn't aware that an identical pieces are in existence? Prints, for example are numbered 1/20 (e.g.). Should a responsible artist do something similar with identical paintings? I guess this is a rhetorical question, because for me the answer is clearly yes - yes, for disclosure, if not necessarily numbered as a print would be.

Tom, I agree with you. It's best to be open with what you're doing, as one wouldn't want a collector to be surprised by finding a multiple original. I suppose that the expectations vary from artist to artist. Some artists tend to do a series of originals that are hardly distinguishable from each other. One of the reasons that copying was not frowned on among academic artists is that they regarded the main creative act as taking place in the planning and design and conception, not the actual execution of the painting.

How very strange that we have now come full circle - picking up on your last remark, James - and creativity is once more considered by the art establishment to be in the design and planning not the execution. I am thinking of Damien Hirst et al. Anyway, I wanted to ask you re copying to learn, do you have to try to use the exact same techniques to learn? I would do more - inspired by your very impressive postcard stand - but I like working alla prima if I can and shudder at the idea of grisailles and endless tedious glazes. I don't know if you would think it pointless to "copy" a Rembrandt if you didn't work in the same way.

Karen, actually it was the academic painters like Bouguereau that believed creativity was in the planning stages. Which is not to say that the execution is trivial. No one could copy a Bouguereau better than the man himself.

About your question, I'm of the opinion that you can learn a ton by copying at a smaller scale or in a different medium. Students in the French academies also did "croquis," small, thumbnail sized copies, usually in pen and ink, of great compositions in art museums. There's also a value to copying at size from the original using the same techniques.

I think what Hockney said via Helena is right on: copying lets you see through another artist's eyes. It's totally different from just looking at a picture that you admire. You sort of absorb it into your blood.

I agree that copying is a great way to learn. I think it should be clearly stated that there is a huge difference between copying non-copyrighted works and copyrighted works. I believe when copying non-copyrighted works is is traditional to sign the painting "After so-and-so" and do so on the front of the painting - presumably in the same area that the original is signed by the original artist. It needs to be visible, so signing only on the back won't cut it. That's my opinion - I'm sure there is no legal interpretation.

As for copying copyrighted works - that should be for practice only. Selling it is a complete no-no. (And possibly a copyright violation crime). If I were to copy a Gurney original, for example - even if I sign it "After Gurney," I am essentially stealing money that is rightfully his.

Dave~ even with the old masters, regardless of how long they have been dead, always check about copyrights! Those copyrights may well be held by someone, a museum or other entity.

Great topic James. Reminds me of art school when copying an old masters was an assignment! I did Michelangelo's study of two apostles for the last supper.

I recall a segment on a news program several years ago (Sunday Morning on CBS, perhaps) that was on copying old masters paintings from life at one of the museums in Europe (don't recall which one). They allowed artists to set up their gear in the museum and paint, and selling their works was okay, as well. The only stipulation was that the copy had to be at LEAST one-third larger or one-third smaller than the original.

Glen Brown copies art and gets 5.7 mill? WTF? This reminds me of how Roy Lichtenstein swiped panels from comic books, and they sell for big bucks. What an absurd and warped perspective on the value and importance of art, in the grand scheme of things.

I was somewhat struck by that photograph picturing a thousand Chinese painters, and the way they are copying away that very same Repin portrait.

Hopefully for some of them, this will be just a transition and learning process from imitation to an own style and expression; as we can so nicely follow up in Jame's case and blog.

But methinks the majority in this huge studio is just looking at some profitable place in copy-cat-business, in a somewhat typically Chinese way ;-)

A good copy made for study can unexpectedly become a big deal. My mom did a copy of a Van Gogh as an art school assignment. It was done in oils on posterboard prepared with acrylic gesso, smaller than the original. She was going to throw it away, but a family member demanded to have it to hang on the wall. Then the framing shop insisted it be put into a special classical frame with gold leaf, considering that it was a copy of a master. All the time my mom is saying, "I hope it doesn't fall apart in 20 years. It was not painted on anything archival quality."

Kevin, not to turn this into a copyright debate, but there is no museum in the world that owns the copyrights to any Rembrandt painting. They own the paintings, or those paintings are on loan from someone, but no one owns the copyright. Copyright lasts for 70 years after the death of the author (painter), plus 25 years after automatic renewal and possibly another 65 years if renewed by the author's estate. Museums are not part of the author's estate. It's even been tested and found that a photograph of an old master's painting can not be copyrighted, which is why museums can be quite nasty about someone taking photos of works hanging on the wall.

I only now took a few minutes to look at the Bouguereau by Bouguereau. The comparison raises a couple of interesting questions. I wonder what his process was like? They're so identical in terms of the placement of the major shapes and lines, that it would seem that a direct transfer method was used for the drawing/cartoon. What remains to be done then (if I'm right) is little more than coloring. It's hard to imagine the master taking the time to do that, but I suppose that could be the case. Or could it have been an assistant's work? Speaking of coloring, the coloring differences - allowing for differences in reproduction - are striking... I even get the imopression that the one on the right might in an unfinished state, noting the distant background, and the lack of detail in cupids hair and some of the foliage.

Thanks Dave. No debate needed. That is exactly correct and glad that it was clarified!

Great post, James!

I give a couple of Master Copy assignments to my students each semester and I believe fully in the practice.

One is pen and ink the other oils. The artists are illustrators (it's an illustration class): Daniel Vierge, Edwin Austin Abbey, Howard Pyke, Joseph Clement Coll, Franklin Booth, Frank Frazetta, Milton Caniff, Bernie Wrightson, Jeff Jones for the pen and inks. Howard Pyle, N C Wyeth, Harvey Dunn, Dean Cornwell, Meade Schaeffer for oils.

They have to work 18 x 24 or larger for the oils and I tell them that I'm looking for forgeries. Stroke for stroke, line for line, value for value, color for color.

These assignments really tend to lay bare the students various deficiencies in drawing, shape, color, value, composition, you name it. And invariably their own work is enhanced because of it and made better for it.

It's how I learned, really, and thank God for it as art schools fall very short in hands on information on how to paint. I had wonderful teachers in school, to be sure, (Barron Storey, Dave Passalaqua, Gerry Contreras, Donn Albright) as well as artists I sought out and who took me under their wing (Jeff Jones, Bernie Wrightson, Mike Kaluta, Joe Kubert, Milt Kobayashi, Skip Liepke, Burt Silverman, etc.). But I basically had to figure most of this stuff out by just going out and painting my ass off.

Luckily I was looking at and copying artists who really knew what they were doing. :)

But I've heard some teachers actually talk this method down and I've never understood their negative attitude to it.

George, what a great set of assignments. I would have dreamed about that as an art student. I learned so much from exercises like that. Copying was a big part of the French academies, and should be a central part of every art school.

I've always had this fantasy of asking great artists of the past if they would mind if I copied their work to learn from them. In my fantasy they would always answer, "Oh, don't look at my artwork. Go straight to nature. That's where I got everything." Which is easy for them to say, and they're right, I suppose, but one needs trailblazers before one can explore the frontier.

I remember going to the Louvre and seeing artists set up throughout copying various works of art. It was actually quite fascinating to watch.

This article about the "Art of Copying" is very interesting.

I think, that copying (or making variations of images) should be open, not like http://www.pinterest.com/pin/366410119658244159/ (even though M. C. Escher is famous).

A good example for legitimate and even masterful "copying" (as a means of conundrum construction) is given by Mahendra Singh and his version of Lewis Carroll's "The Hunting of the Snark". I learned to know Mahendra after I stumbled over Henry Holiday's "copies" in his illustrations to Lewis Carroll's "The Hunting of the Snark". Mahendra consciously explained his technique openly and Henry Holiday didn't. I think it is legitimate in both cases.

After I found Holiday's allusions, I was puzzled by the responses of "Carrollians". Many of them where put off and thought, that I call Holiday a plagiarist. But he wasn't a plagiarist. He just paralleled Carroll's textual allusions by his own pictorial allusions (perhaps in cooperation with Carroll/Dodgson and surely with Joseph Swain). His "copying" probably was a more tedious work than just drawing what came into his mind.

Best regards from Munich

Götz

There is a copy of J. E. Millais' "Christ in the House of his Parents" which Rebecca Solomon made under the guidance of Millais. Probably several on-line reproductions of that painting are by Solomon and not by Millais.

And I think, that Millais did not only support this copying. He also may have legitimately copied and modified shapes and concepts of at least two other artists in order to use them in "Christ in the House of his Parents" as reference to the source paintings and their meanings.

Best regards from Munich

Götz

I read in "the lives of the artist", that Michelangelo borrowed a drawing by Durer, and he copied it, and then kept the original and returned the copy. I wonder today which one would be more valuable.

I also read about a guy who enjoyed copying master paintings. But before he started, he would take lead white and write "fake" on the white canvas, so that if it was ever x-rayed, they would know.

Post a Comment