When I paint an imaginary scene in oil, I usually try for three strategies in the first statement:

When I paint an imaginary scene in oil, I usually try for three strategies in the first statement:1.Establish the overall color temperature for each region of the picture.

2. Suggest the large tonal statement of light and dark.

3. Keep everything a little lighter than the final rendering will be.

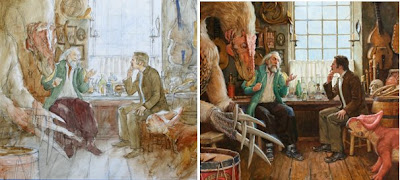

Following strategy #3 leaves you the option to achieve your final color rendering either transparently or opaquely. If you go too dark too soon, you can only correct it with opaques. Comparing the first step with the final below of Old Conductor from Journey to Chandara, the washin should look like the intended finish with a piece of tracing paper laid over it.

The reason for #2 is that every judgment needs to be seen in context. If you paint each area starting from white, like paint-by-numbers, it’s harder to make accurate choices. It can be done, but to me it makes more sense for observational work.

The reason for #2 is that every judgment needs to be seen in context. If you paint each area starting from white, like paint-by-numbers, it’s harder to make accurate choices. It can be done, but to me it makes more sense for observational work.The first strategy could be called a color imprimatura. A moonlight scene might be washed all over with a light blue-green. If the scene has different colored lights, each light region should be bathed in the color of each source. If there are multi-colored light sources, a white object will take on the relative color of each source.

------

Thanks to Online University Reviews for naming Gurney Journey one of the "100 Best Scholarly Art Blogs" (#65, right next to my buddy Tony DiTerlizzi.) Kudos to my assistant professor, my budgie!

------

Earlier post on "Area-by-Area" painting, link.

Part 1: Initial Sketches

Part 2: Researching Insect Flight

Part 3: Maquette

Part 7: The Painting