Time lapse can compress a slow, repetitive series of steps into a short segment of time. A typical time lapse interval is one frame per second, which compresses an hour into

a minute two minutes. You can create a time lapse with a

GoPro

or a

mirrorless camera

, both of which have built in

shutter release timers

. Time lapse can aid the viewer's understanding of the overall painting process or show the broad-scale strategy of a time-consuming step. You can also speed up footage that was shot in real time, but that puts demands on your

external hard drive

.

But time lapse can have an unreal, detached quality that can be frustrating for viewers who want to understand how long each step really takes.

|

My most-watched YouTube video is called "Street Painting in Indiana"

It's about 10 minutes long, and it has a variety

of coverage and a little bit of drama. |

The advantage of shooting in real time is that you can show what happens with each brushstroke. Painting can take many hours of repetitive action, and it usually needs to be edited down to make it watchable.

A good solution is to select representative excerpts of each stage and cut or dissolve between them. As long as you don't jump-cut across a big change, the viewer will hardly notice that they're missing anything.

How can you get the best of both worlds? One solution is to show an

analog pocket watch

in the frame of your time lapse so you can actually watch the minute hand go around. Another thing you can do is to alternate time lapse with real-time footage, using time lapse when you want to show the long-term result of an extended repetitive action, and real time when you want to bring the viewer into the moment. When you change the speed, tell the viewer why you're doing it in the voiceover.

Since time lapse comes without audio, I would recommend using voiceover to explain what’s going on. You can include real-time recorded audio of painting sounds under the time lapse footage, even if that sound doesn't correspond exactly to the action. Either way, you want the audio to connect the viewer with the real-time experience of painting.

|

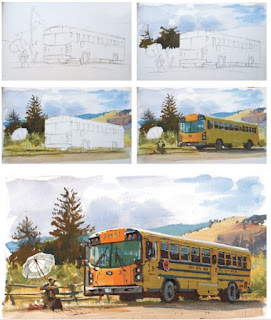

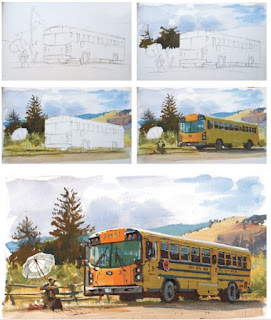

Screenshots from my video “Snyder Swamp.” Even though the video

is only 1.5 minutes, I made sure to get the following shots

(reading across from upper left): 1. Establishing shot; 2. Easel setup;

3. View of scene; 4. Detail of palette; 5. Detail of painting; 6. Detail of foliage |

Music

People often use low-level music throughout the whole production to cover bad or missing field audio. Not everyone agrees on musical taste. Personally, I can't tune out low-level music in a video, especially if it endlessly repeats. I tend to fixate on it, which distracts me. The actual sounds of the painting environment are usually more immersive and compelling.

However, there are times when a piece of music is really central to the concept of the piece. Music usually works best if you restrict it to the first and last minute of the video, or when you use it for transitions. In the first minute it sets the emotional tone, and in the last minute it signals the impending close. You can also use music to flavor an interlude of short montage cuts, which can show important details or set a certain mood. Make sure you capture a long take of field audio or voiceover for the body of the video, because you don't want to jump-cut the resident audio from clip to clip.

Music must be cleared for copyright before using it in a video. You may be able to use copyrighted music if you ask permission or give credit. Copyright-free music is available for free from

Kevin MacLeod in exchange for credit and links. Another source is

Freeplay Music, which lets you use music for free as long as you don't generate income from your video (thanks, NextMoran).

Freesound is a website with a lot of user-uploaded sound effects that have a variety of usage licenses. The iMovie software has a range of free music, and you can also get free music and sound effects from

YouTube’s Creator Academy.

How long should an art video be?

|

School Bus, 2014, gouache on watercolor paper,

A video for a painting like this needs to

compress the action of two or three hours

into about 10 minutes, and to demonstrate

the important choices made at each step. |

Answer: As long as it needs to be—but not one minute longer. How many of us own a multi-hour video tutorial sitting on the shelf unwatched, or one that we have watched just once?

Why should a painting tutorial need to take two, three or four hours? Who wants to watch someone paint every blade of grass? That would be like watching a cooking video showing onions slowly caramelizing in the pan. These long art videos result from the assumption that the video is equivalent to a real-time workshop. It’s not the same thing! In an actual workshop, you're freely in control of your attention, but in a video, your attention is locked down and passive.

To have genuine instructional value, a video should show each step clearly, but it should skip over or compress repetitive actions. Unless you really need to demonstrate a complex series of different steps (such as researching, building maquettes, thumbnailing, posing models, grinding pigments, stretching canvases, etc), the story of a single painting probably doesn’t need to take more than 45 minutes.

I know that I have probably made a few videos that seemed too short, but that's usually because I just just didn't capture any more coverage.

Suggested running times for art videos

- 1 hour: a case study of a multifaceted project like a mural or a researched illustration, with many separate actions in addition to the painting sequence itself, where each step receives thorough but concise coverage.

- 15 - 30 minutes: a single painting presented as a case study, with each step of the painting demonstrated in detail from start to finish.

- 5 - 15 minutes: a location-based painting or studio life study that is relatively straightforward

- 3 minutes: a painting sequence boiled down to its essentials, and focusing on just two or three principles, ideal for YouTube.

- 2 minutes: a promo piece, highlight reel or trailer.

- 1 minute: a video that makes a single point, ideal for Instagram, ebooks, apps, or online presentation.

(

Link to video) Here's an outtake from the next video feature, which I'm editing now.

Editing

There are a variety of professional and entry-level editing programs, including

Adobe Premiere Pro

,

Final Cut Pro

,

Sony Movie Studio

and

iMovie (which comes with your Mac)

. All of them let you juggle the order of clips around, change their lengths, color-correct, zoom in, crop, and add multiple tracks of audio.

I would suggest restricting the use of transitions to simple cuts. Use dissolves for transitions that bridge a gap of time. Start with your strongest visual, or express immediately what you want to accomplish, and if you want to title the video, put that a few seconds in, but not at the very beginning. Use subtitles to identify anyone who is talking on camera, to explain where you are, or to name pigments you're using.

|

Painting iceboats on the Hudson, March 2014. The simplest setup

is a down-facing camcorder on a tripod while you hold the

sketchbook in your lap. By extending the legs of the tripod unevenly,

the camera can lean out over your work. |

Distribution

There are many ways an instructional video can serve your goals. As a promotional tool, a video brings your methods to life, connects your paintings with your personality, and reveals the circumstances of your painting’s creation. It can give your students a lasting record of your teaching methods, and can connect you with your collectors by sharing behind-the-scenes insights about your inspiration.

You can share promotional videos on YouTube, or sell downloads via digital content distribution services like

Sellfy or

Gumroad, which take only a tiny percentage of the sale.

Kunaki is a disc producer that will produce shrink-wrapped DVDs on demand with Amazon-ready bar codes.

Media devices like smartphones and tablets offer opportunities for presenting your art together with text, audio and video in formats. We've developed an app called the

Living Sketchbook that lets you page through a complete sketchbook with high res scalable files and experience audio and video taken at the time of the painting.

There’s no reason that videos about the making of art shouldn’t be artistic as well as educational. As the great director Jean Cocteau once said, “Film will only become an art when its materials are as inexpensive as pencil and paper.”

----------

Read more in these previous posts:

I have 11 painting tutorials so far