How do you get exactly the colors you want in a picture….and no others?

This is the third post in a Sunday series about a method called color wheel masking. The

first post showed how color masks can help to analyze color schemes, and the

second post explored different shapes of masks.

In this post I’ll demonstrate how to actually mix the colors you have chosen for a given painting.

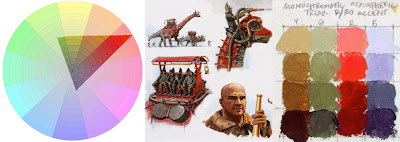

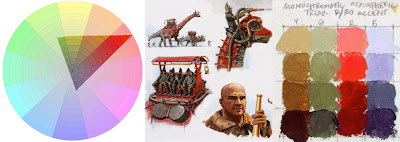

To start with, here’s the color wheel on the left. To the right above the palette paper are some primary colors of oil paint. You can use as many tube colors as you want at this stage. I just have little demo dabs of Winsor Red, Cadmium Yellow, Titanium White, and Ultramarine Blue.

Let’s say you want a monochromatic atmospheric triad with the dominant (and the most saturated) color in the red-orange range. Using your palette knife, mix a batch of each of the three colors that you see in the corners of the triangular gamut.

I've placed a little white box over those colors in this photo. In this case, it’s a saturated red-orange, a desaturated red-violet, and a desaturated yellow-green.

Now you’ve created the “heads of the families” or subjective primaries. Next, extend those colors into four different values or tones. Try to keep the hue and the saturation constant as you do so.

Look again at the color wheel mask. Halfway along the edge of the triangle are little marks indicating your secondaries. These are your in-between colors, which you may want to mix as well. You may end up mixing and working with anywhere from three to six strings of colors.

Before you start painting, remove from the palette all the tube colors that you squeezed out, except for white. This is important, because these colors are outside your gamut. You don’t want to have access to those anymore during the painting process.

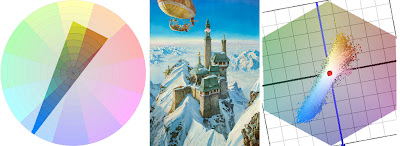

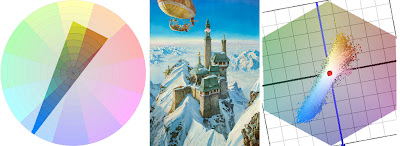

At left is a color wheel with a monochromatic atmospheric triad emphasizing red. This time it’s laid out on Tobey Sanford’s digital color wheel (

link to download). On the far right are the color ranges I mixed. In the middle is the resulting painting from

Dinotopia: Journey to Chandara.

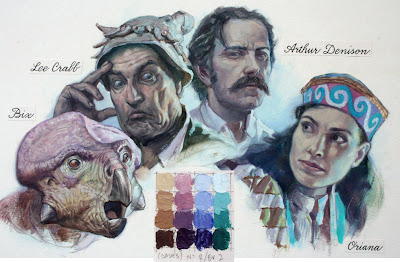

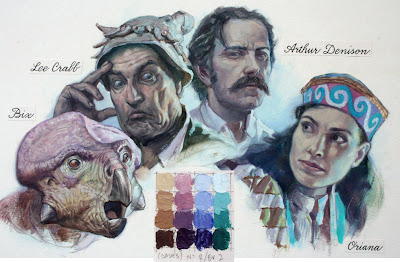

This group portrait takes place in Dinotopia’s phosphorescent caverns in the book

The World Beneath (1995). I wanted the colors to suggest a cool, magical ambiance. With the colors in this gamut, it’s impossible to mix any intense warms, even if you wanted to. But as your eyes adjust to the color mood, it feels complete. The relative warm colors appear warm enough in the context of the picture.

I have noticed that when I use the color wheel masking system I am more careful to keep the brushes clean and to push against the outside of the range. Harmony and unity are a given, so the effort goes into reaching for accents. It's the opposite of the color-mixing mindset when mixing color from a full palette of tube colors, where I'm always neutralizing mixtures.

To conclude, here’s a painting from

Dinotopia: A Land Apart from Time (1992), about the time when I first developed this method. I have digitally reconstructed the gamut I used for the narrow complementary color scheme.

Blog reader Briggsy provided the diagram on the right. He processed the image through a filter created by P. Colantoni, and available for Windows users at

couleur.org. What you’re looking at to the right of the painting above is an objective computer visualization of the actual color scheme.

As you can see, it corresponds pretty closely to the generating mask, proof that the system is giving us exactly the intended color scheme. The blue colors are very intense, almost touching the edge of the wheel. The rest of the colors are in a narrow swath running across the grey center to the weaker complements.

I look forward to hearing how this method works for you, either with traditional or digital techniques.

Tomorrow: Pinkwater Portrayed

Take one part Jules Verne, add a dash of Steampunk, mix in a little Cirque du Soleil and you've got the Royal de Luxe, a French street theater company that has staged magnificent performances in London, Antwerp, Calais, and Santiago.

Take one part Jules Verne, add a dash of Steampunk, mix in a little Cirque du Soleil and you've got the Royal de Luxe, a French street theater company that has staged magnificent performances in London, Antwerp, Calais, and Santiago. But the elephant is just part of a carefully planned series of events that unfolds in each of the lucky cities who host the show. There is also the giant girl, one of the dreams of the sultan. She interacts with the elephant, licks a lollypop, and lets a few children from the audience ride on her arms.

But the elephant is just part of a carefully planned series of events that unfolds in each of the lucky cities who host the show. There is also the giant girl, one of the dreams of the sultan. She interacts with the elephant, licks a lollypop, and lets a few children from the audience ride on her arms.