On the GJ Book Club, we're studying Chapter 6, "The Academic and Conventional" in Harold Speed's 1917 classic The Practice and Science of Drawing.

The following numbered paragraphs cite key points in italics, followed by a brief remark of my own. If you would like to respond to a specific point, please precede your comment by the corresponding number.

-----

In this chapter, Speed is searching for the "real matter of art" that raises it above correct, accurate, but lifeless drawing.

1. "dull lifeless, highly finished work, imperfectly perfect"

Speed later speaks about the mistake many art schools made by limiting themselves to "training students mechanically to observe and portray the thing set before them to copy." This is a familiar criticism that we hear today about students coming out of modern-day atelier training.

2. "freer system of the French schools"

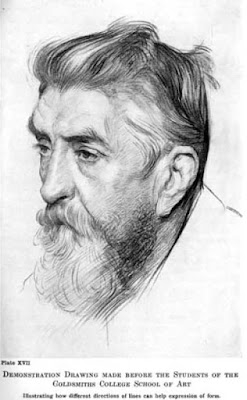

|

| Drawing by Harold Speed |

3. "These accurate, painstaking school studies are very necessary as a training for the eye in observing accurately."

I'm glad he said this, because too often one hears complaints about academic drawing from those who can't do it, and too often, "artistic" styles are used to justify art that is not disciplined.

3. "Dither"

Speed says, "It is difficult to explain what is wrong with an academic drawing, and what is the difference between it and a fine drawing." He introduces the concept of "dither," a Scotch word meaning the looseness or play of machine parts that allows an engine to move. In art it would mean the search for variety and the quality of "a live, individual consciousness."

4. The fact is: it is only the academic that can be taught.

I don't think Howard Pyle would agree with this. Pyle had students like N.C. Wyeth enter his summer school for illustration, and he taught them how to see with the mind's eye, and how to make their compositions more forceful. Most of Pyle's students had already had Beaux-Arts style cast drawing and figure drawing experience, but he showed that non-academic skills (such as storytelling skills) can indeed be taught.

5. A drawing is not necessarily academic because it is thorough, but only because it is dead.

Important distinction. Tightness or comprehensiveness isn't necessarily bad. Two people can each work methodically on a drawing for weeks, and one can be artistic, and the other not.

6. Madame Tussaud's Waxworks

Speed invokes the wax museum figures to criticize work that is overly realistic without selectivity and expression. The same sort of criticism has been addressed recently to certain CGI animated films or visual effects that have too much realism. Speed says that even if one departs from naturalism and delves into more abstracted forms, the artwork must be sincerely felt by the artist for them to have any emotional effect. That's a problem faced by artists who unquestioningly adopt the Disney or manga cartoon character formulas.

7. The struggling and fretting after originality that one sees in modern art is certainly an evidence of vitality, but one is inclined to doubt whether anything really original was ever done in so forced a way.

As true now as it was a hundred years ago.

8. Every beautiful work of art is a new creation, the result of particular circumstances in the life of the artist and the time of its production, that have never existed before and will never recur again.

This is a good reminder to all of us who admire past styles. We can learn from Rembrandt or Velazquez, but we can't see fully into the heart of those artists because our worlds are so different. The risk is that all we'll absorb from them is the external features of style, the very thing we're trying to transcend. Any work that we create should respond to the unique features of our own time and our own individual chemistry. By this argument, all work is contemporary and all work has the power to surprise its viewers.

|

| Graphite drawing by Adolph Menzel |

Speed uses the example of the treatment of hair by sculptors. He says that artists should be fully engaged with the materials they are using, whether it is stone or bronze or oil, graphite or charcoal. An experienced artist knows the range of possibilities of the medium they're using, and selects the aspects of nature that can be translated into that material with the tools at hand. The drawing above by Menzel is a great example, one that transcends the conventional, is full of life, and is perfectly suited to the materials he was using.

-----

The Practice and Science of Drawing is available in various formats:

1. Inexpensive softcover edition from Dover, (by far the majority of you are reading it in this format)

2. Fully illustrated and formatted for Kindle.

3. Free online Archive.org edition.

4. Project Gutenberg version

Articles on Harold Speed in the Studio Magazine The Studio, Volume 15, "The Work of Harold Speed" by A. L. Baldry. (XV. No. 69. — December, 1898.) page 151.

and The Windsor Magazine, Volume 25, "The Art of Mr. Harold Speed" by Austin Chester, page 335. (thanks, अर्जुन)

------

GJ Book Club Facebook page (Thanks, Keita Hopkinson)

Pinterest (Thanks, Carolyn Kasper)

Overview of the blog series

Announcing the GJ Book Club

Chapter 1: Preface and Introduction

Chapter 2: Drawing

Chapter 3: Vision

Chapter 4: Line Drawing

Chapter 5: Mass Drawing

Chapter 6: Academic and Conventional

Chapter 7: The Study of Drawing

Chapter 8: Line Drawing, Practical

Chapter 9: Mass Drawing

Chapter 10: Rhythm

Chapter 11: Variety of Lines

Chapter 12: Curved Lines

Chapter 13: Variety of Mass

Chapter 14: Unity of Mass

Chapter 15: Balance

Chapter 16: Proportion

Chapter 17: Portrait Drawing

Chapter 18: Visual Memory

Chapter 19: Procedure

Chapter 20: Materials

1. Inexpensive softcover edition from Dover, (by far the majority of you are reading it in this format)

2. Fully illustrated and formatted for Kindle.

3. Free online Archive.org edition.

4. Project Gutenberg version

Articles on Harold Speed in the Studio Magazine The Studio, Volume 15, "The Work of Harold Speed" by A. L. Baldry. (XV. No. 69. — December, 1898.) page 151.

and The Windsor Magazine, Volume 25, "The Art of Mr. Harold Speed" by Austin Chester, page 335. (thanks, अर्जुन)

------

GJ Book Club Facebook page (Thanks, Keita Hopkinson)

Pinterest (Thanks, Carolyn Kasper)

Overview of the blog series

Announcing the GJ Book Club

Chapter 1: Preface and Introduction

Chapter 2: Drawing

Chapter 3: Vision

Chapter 4: Line Drawing

Chapter 5: Mass Drawing

Chapter 6: Academic and Conventional

Chapter 7: The Study of Drawing

Chapter 8: Line Drawing, Practical

Chapter 9: Mass Drawing

Chapter 10: Rhythm

Chapter 11: Variety of Lines

Chapter 12: Curved Lines

Chapter 13: Variety of Mass

Chapter 14: Unity of Mass

Chapter 15: Balance

Chapter 16: Proportion

Chapter 17: Portrait Drawing

Chapter 18: Visual Memory

Chapter 19: Procedure

Chapter 20: Materials

13 comments:

This post resonates strongly with me. Drawing comics, I found that sticking to close to reality often really hurts the dynamics of the drawing. This is not to say that I don't see the benefits of learning to draw in the academic way. I just believe that, especially in comics, the most important thing is to be fun and dynamic. One should be careful to not get trapped in realism or any "style" for that matter.

I enjoyed this chapter a lot. I don't have anything to add this week but wanted to say thanks for the GJ book club. It's a highlight of my week.

8 | I think about that every time I'm in a museum.

Google knows all:

http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:iFIkE0mDlJgJ:gurneyjourney.blogspot.com/2015/05/gj-book-club-chapter-5-mass-drawing.html%3FshowComment%3D1430864502872+&cd=16&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

Thanks, Mitti! That's so resourceful of you. I copied, pasted, reposted, and backdated the Chapter 5 post, complete with all the comments, thanks to you.

Thanks for saying that, Jared. I feel like it's my homework each week, and it makes us all read the book in a different way than we would have otherwise.

Emmanuel, great points -- good to get the perspective from someone not working in a realistic way.

Item 8 hits me differently too. I had an instructor in art school who had some incredible life drawings on his wall. I asked about them and he replied that he'd done them all on a day when all the forces came together and he saw and was able to draw with incredible fluidity and clarity. He said that some days all the things fall together and you do create works that you cannot repeat as you can't be there again mentally and emotionally. I've heard this referred to as 'being in the zone' in the past as well. I recall only too well some days in life drawing when things just didn't click, and days in which getting the right lines seemed effortless. I'm not sue that this is what he's referring to, but I know that others have this same experience. Golden moments, I suppose.

Hi James,

Thanks for sharing your knowledge and love of great old books, and helping us glean some useful points from them!

For some reason I've always been able to what I think is my strongest work within the context of an academic exercise. (Not being a professional fine artist) Perhaps it's the limitations of the study - a limit on materials and format that have helped me focus my attention on to the task. Have others had the same experience?

I really want to submit an entry into a local competitive juried fine art show this fall, and wonder how I might move from my typical loose "on the spot" sketches, to a work that might be taken seriously by jurors recognized in their media...it seems like this chapter has a lot to say on this, but I am curious of what others think.

I love the loose preparatory sketches of the great masters, but doubt my loose sketches would hold their own, even if they have energy and capture an uncanny likeness and character in a few economical lines. :) Any thoughts?

Dean, one quick thought: You might do a piece where you're really selective about which areas you finish tightly. What if you spent 90% of your effort carefully rendering one key area, really knock it out of the park— —and then handle the other areas loosely? Another thought is to do two or three on-the-spot sketches and then work them up in the studio (with or without photos) to create a work that transforms or heightens the scene in some way.

Tim, yes, that's definitely a reasonable way to think of Speed's point. I like the way the Greeks personified the agent of inspiration as an angelic female figure who would visit the artist: http://www.oceansbridge.com/paintings/artists/a/aman-jean_edmond/oil-big/hesiod_listening_to_the_inspiration_of_the_muse.jpg.

It's been a while since I've read this book. Probably a good time to pick it up again and glean some new insights.

The mindset of the futility of a stiff, scientific and dead representation of reality was prevalent through my education in fine art. They seemed to be more concerned with producing work that was something new and exciting. Rushing past the fundamentals felt, to me, like trying to build an exquisitely modern home on a pile of mud.

3. "Dither": interesting what he says about things getting either too thight or too loose, the analogy may apply to other domains as well. Since Speed's writings the "parts of the machine" in the art world have perhaps further "dithered away" to the point of disintegration;-)

8. "Every [beautiful] work of art..." To begin with, we are establishing a convention among us that what is beautiful can be recognized by us all. Then, the corollary to this assumption are the considerations that: (a) artists have good days and bad days; they handle the composition with passion or difficulty. I never know until I'm in the final stages of a painting if what I've done is superior or pedestrian. (b) like musicians whose music moves us with such emotion during the early years when they are struggling with hormones, love, altruism, political inexperience, the vagaries of the road, etc., which, after the money is made we no longer connect with songs about lawyers in love, the struggles of the uber-rich, and the environment of wealth that inspires those who have made it, artists/painters are also subject to these changing socio-economic environments that inform their art. Consider that I am making this statement from my own sense of beauty, which may be entirely different from yours, due to my age, my experiences of life, my education of what others have considered beautiful, etc.

"Any work that we create should respond to the unique features of our own time and our own individual chemistry." Aside from subject matter, what are some unique features of our own time, especially if I want to paint Yosemite? As an artist I have my chops just like a guitarist. I learned these chops from other artists, videos, books, museums. I chose from the plethora of chops to which I was exposed that which appealed to me. Doesn't mean I'll be able to create beauty. I'd love to understand better how to recognize the unique features of our own time, and I'll have to take my chances with my own individual chemistry.

I have much to think about regarding "external features of style, the very thing we're trying to transcend". I suppose this implies that there is an internal feature of style which we pursue, and I give this little attention because I am NOT a master of my craft, allowing this internal style to manifest over time and brought to my attention by others. I admire style, I copy style to inform me of what it is, how it feels, but I never paint with this in mind. With apologies to Nike, I just paint.

Just read a citation in Steven Pressfield's The War of Art that seemed fitting:(Socrates, in Plato's PHAEDRUS):

... If a man comes to the door of poetry untouched by the madness of the Muses, believing that technique alone will make him a good poet, he and his sane compositions never reach perfection, but are utterly eclipsed by the performances of the inspired madman.."

I think I have an idea of what Speed may mean between mechanical accuracy vs artistic accuracy, and "dither."

I remember watching a video of Morgan Weistling painting, and he talked a bit about what his teacher, Fred Fixler, taught him. (Fixler comes from the Reilly lineage, I believe).

He talked a bit about drawing with beautiful shapes. He wasn't just trying to do a block-in and nail down exactly the shapes he was seeing in a mechanically accurate way. Instead, he talked about how the shapes themselves should be pleasing in an abstract manner. He discussed how the shapes shouldn't look like a jagged road map, but rather, more simplified and designed to be beautiful.

Fixler said "if it's sort of straight, make it straight, if it's sort of curved, make it curved."

So, for instance, imagine two people were going to draw a shape similar to the eastern border of Pennsylvania. The mechanically accurate artist would plot out each tilt and angle, making sure everything was spot on accurate. The artistically accurate artist may get the large proportions and landmarks correct, but would simplify it. So the eastern-Pennsylania-border shape wouldn't be 300 jagged shapes, but rather one beautiful S curve.

Pennsylvania map for reference: http://geology.com/state-map/maps/pennsylvania-county-map.gif

I think this is part of what mechanical accuracy vs artistic accuracy may mean.

I really dig the idea of "Dither" Speed mentions. I understood it as breaking up of the monotonicity and apparent lifelessness in an artwork through the infusion of individual consciousness and personality, giving the artwork an accommodating nature towards its viewers.

I stumble onto this exact feeling while listening to music, where some musical compositions seem to accommodate the kind of emotions I have while listening, however different they might be. The great compositions of the past seem to have this quality in them, to make space for emotions of the listener, however varied they might be. So that the song really "lives" bears a new life with each listener. It's amazing really.

Post a Comment