Another related question: If you're not so great at recognizing faces, can you ever be any good as a portrait artist, even if you practice a lot?

A diverse group of participants were asked to draw a likeness based on a photo. The participants were also evaluated separately with various standard face recognition tasks.

The participants included those with some expertise (black frames) and novices at drawing (gray frames).

The drawings were ranked according to a numerical score that was given by judges who didn't know anything about the people who did the drawings. The drawings with the highest likeness scores are shown at the top of the chart. Not surprisingly, artists with practice at drawing got more recognizable results.

But the scientists wondered: what about the subjects who were novices at drawing? Presumably they would not have derived any advantage from training. Would those novices with better native face recognition abilities be more successful at drawing a likeness?

The answer is yes: there is a strong correlation: The ability to successfully recognize faces predicts how well a non-expert can capture a likeness in a drawn portrait.

|

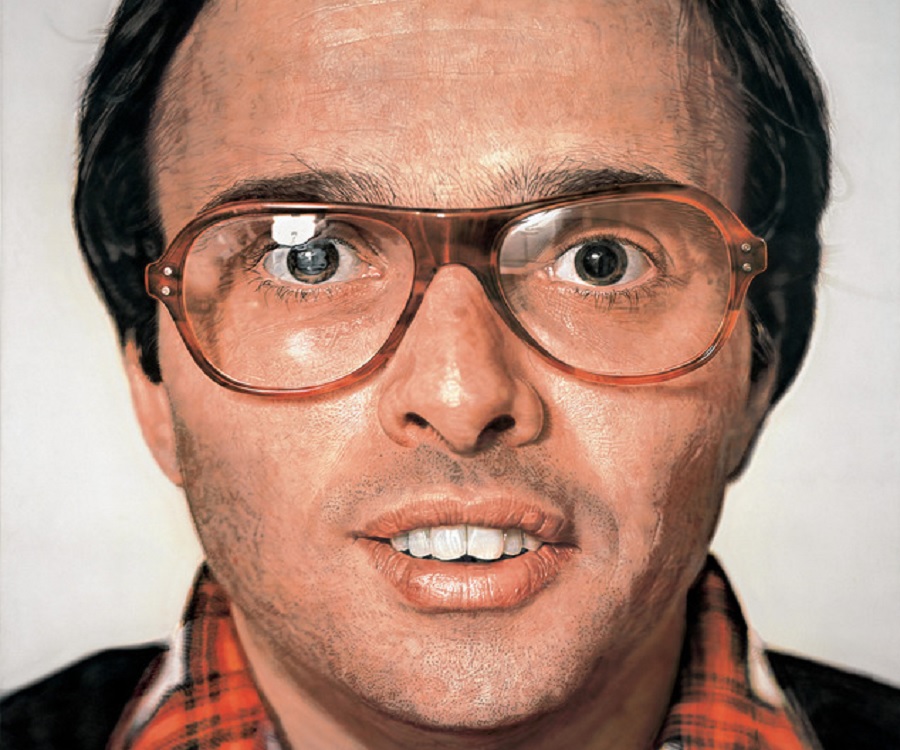

| Art by Chuck Close |

|

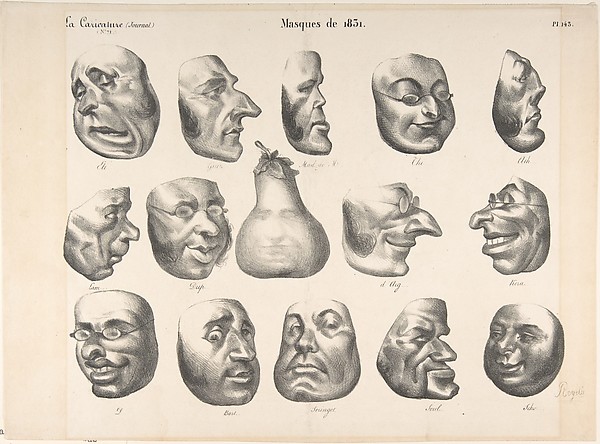

| Daumier |

----

Scientific paper: "Face processing skills predict faithfulness of portraits drawn by novices."

Side note: National Gallery has cancelled a planned exhibition of Chuck Close due to concerns over allegations of sexual harassment

Video: Oliver Sachs talks about face blindness

19 comments:

This is in perfect timing to my own blog post of this week. I was somewhat unsuccessfully saying that while practice is essential it's not having the same results for all of us, because some humans are better equipped than others. I for one have a very bad memory so I forget things rapidly. I practice a thing for months and it gets better then I stop and I forget most of what I learned.

I'm also not very good at recognises faces, nothing major but I am sure it plays a role.

I need to link to this post from my blog.

Very interesting! Do you have a link to the small shape mapping technique? Google is failing me.

I would be curious to know what was the criteria to establish whether one was a novice or not? I would think even those who described themselves as novices still must have drawn as children.

I think all drawing ultimately boils down to the relationship between one mark, line or brushstroke relative to the next.

Knowing general human proportions will get you a great start to capture a likeness. To excel one has to have the ability to observe subtle variations from those general proportions in the individual whose portrait they are trying to capture as well as the skill to record those variations with their medium of choice.

I think this is where Bargue's methods are essential for students or anyone looking to increase their ability to capture a likeness. Training your eye and hand is what Bargue's methods were all about.

Triggered by your post I ended up doing a three part face recognition test:

https://greenwichuniversity.eu.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_e3xDuCccGAdgbfT

Some bits were quite hard, but maybe someone would like to try it as well.

Interesting how the recognising skills correlate with the artistic abilities of a graphic artist, I never thought about that, but obviously makes sense.

I also can cartoon fairly well.

I am very interested in that research because it is a subjet that directly touches me... and for the same reason, I am very doubtful of the result...

Or may I be a counter example ?

Well... I am experiencing symptoms of prosopagnosia. I don't recognise my editor in a crowd, for example in a festival, if I can't read his name on his badge. However, my portraits are usually right enough...

So I am not sure about the results of this test...

My problem is not to see distinctivly the relationships during the time I sketch but to memorize them. As soon as I turn away, I forgot people faces...

I must say that drawing people help me fix their features for a longer time.

Enjoyed your post very much, as I do almost all your posts. Nice and varied topics.

In this case, I firmly believe in discussing with students the fact that people attempt to draw based on what they think they see rather than what they actually see. Training in drawing, I feel, really helps people overcome the thought process of drawing what they think they see that can lead them astray while teaching them basic structures to help them draw what they actually see does work.

Way back when, I was given plastercene (sp?) in a class and was led through the process of making a skull replica with it. That function alone taught me about all the dips and hollows created by the skull bone structure. Then we added a layer of skin out of the same product. Great learning experience. I still struggle sometimes but going back to the basics sure helps, even with understanding what I am looking at. Training can achieve a lot.

Thanks again for this post. I enjoy my daily read.

So I sit on a plane and pick an image in a magazine to draw in my sketchbook. Usually in pencil and lately with watercolor added. I've been doing this for a long time, although since retiring I don't spent near as much time in the aluminum tube as used to. I've been drawing (copying...) since I was a snot nosed brat. I consider myself a "trained" eye but every drawing I'm surprised at what I don't see, or better said, don't see accurately.

The right leg is extended further, the head is smaller/bigger, the hand is shorter/longer and facial features are a whole different category. Although I'm pretty good with recognizing faces, getting them down on paper seems to bear no correlation for me. Don't know what it all means but for me forcing myself to draw in caricature (itself a great challenge) is one thing that works consistently.

the other thing that works is drawing often ("not a day without a line" right James!), No matter the subject, making a line each day has been the best medicine for me.

As a portrait artist and a long time teacher, it’s my opinion that capturing a likeness is a function of combining objective observation with subjective interpretation. To me, facial recognition ability, understanding proportions, great visual memory and knowledge of anatomy are but a few examples of conventional thinking that proove useless when it comes to truly captuing a likeness, because they contaminate your ability to see what’s really in front of you. Just one man’s opinion.

Following my face recognition test comment earlier, I wonder if being left- or right-handed has also an significant effect, especially when with left-hander the right cerebral hemisphere dominates, where part of the face recognition seems to happen.

Fascinating topic ...

I wonder though if sometimes the opposite might be true when one is trying just to copy. Like for example how artists are often taught to turn the image they're copying upside down so they focus just on the shapes, forms, and values, and not what an object is.

I don't have problems recognizing people at all, I'm that guy that can always spot and actor and tell you everything they've been in, but I struggle with the more subtle emotions. Like smiling, frowning, etc, I get, but others I'm often not sure about sometimes. Doesn't mean I can't copy them though and I've learned many of them mechanically (by reading how different facial muscles pull during what expressions), so I'm sure one can overcome the problem if necessary. I'm willing to bet the face-blind artists could probably draw better than the non-artists who could recognize faces very well.

I have a corollary question -- don't you capture a better likeness if you know your subject, and so know how they "really" look? Or perhaps I get better at drawing the same model simply because of the practice! But some people do look quite different from day to day, and it helps to know which appearances are more typical and true.

Yes, thanks, James, for raising yet another fascinating topic!

I am terrible with faces, I suspect I would qualify for aphantasia. I don't do caricature, partly owning to the fact that it involves a creative element that I can't manage. When I look at something, I can come up with a decent enough representative/realistic image of it. If I look away, I am left with basic icon images. I've tried a few times, if something is missing in a reference photo, to fill in the gap, and it has never even come anywhere close to coming off successfully. My art will always be limited by what I can see, because I can't imagine in images. What details I make up, are always shockingly poor in comparison with other elements. I don't mine though, as the type of art that appeals most to me are the pieces solidly based on carefully observed reality, and with another 40 or so years of practice, I think I'll have them down.

Thank you for an interesting item, and I look forward to more thoughts about caricature.

Speaking personally, it's interesting to me that I am somewhat obsessed with caricature, and at the same time, I am rather poor at recognizing faces. Perhaps this is not coincidence!

I'm face blind and it's really painful how far my likenesses lag behind every other aspect of my paintings. Though I get plenty of commissions I've started turning down ones that involve any sort of likeness, because the number of revisions I'd have to do was just not worth it.

I tried a bit of training by drawing celebrities etc, with pretty crappy results. I can do a decent face, it just won't look like the person unless I literally trace it.

Hi there,

I'm honored you've picked my research for a blog spot, James, and it's been super insightful to read everyone's comments. I thought I would provide more details in response to some of them.

@Joe Kulka, it's a fair assumption that everyone must have drawn at least a little bit as a child, or that many people doodle to some extent, when on the phone for example. We considered people were novice drawers if they had not received any formal education in arts and did not report drawing regularly in the present days.

I'd like to add that we purposely recruit other people who did not have drawing experience either to judge the portraits. The goal was to avoid ratings of faithfulness that would be negatively affected by the detection of drawing inaccuracies (of which there were many) if drawings had been judged by people with expertise in art. Our assumption was that a drawing could be very inaccurate (in terms of proportions, anatomy etc) but still bear some resemblance with the model.

@Tobias Gembalski: We didn't take handedness into account.

@Krystal, your experience is very interesting! The conclusions of the study are based on correlations, so they do not necessarily apply to a given person. Prosopagnosia is still not fully understood, and it could have different underlying mechanisms in different people. As you say, it could for example involve perception or memory in different degrees in different people.

As James also rightly says, there are ways to overcome difficulties with face recognition skills and Chuck Close is the perfect illustration for that.

@Alan North, you might find answers to your question about drawing upside down faces in this other article. The conclusion is that for novices, portraits drawn in normal orientation are more accurate than portraits drawn upside down:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320658936_Physical_and_perceptual_accuracy_of_upright_and_inverted_face_drawings

Maybe that does not hold for professional artists, and drawing from an upside down picture might nonetheless remain very useful to break the habit of drawing what you know instead of what you see.

@Evelyn, whether we would draw people we know better is a very good question and I wonder about that too. We know that people can do simple tasks (like comparing two pictures and judge if they show the same person) with faces of familiar persons much better than with faces of unfamiliar persons. Whether this advantage of familiarity translate into drawing portraits has not been tested to my knowledge. I would say that it could help. On the other end, it might not make a big difference for an experienced artist trained at observing what they see.

@Leif, some research show that caricatured versions of faces are easier to recognize than the original, presumably because they make the features even more distinctive. Maybe it works the other way around too!

@Rebecca Harstein, I was fascinated to read about your experience, and it seems to fit with what I have observed in more informal ways. In the life drawing sessions I attend, some people are excellent drawers from observation and/or from imagination. But among these people who draw remarkably well, some rarely seem to get the face "right". Although the face holds together and the drawing is solid, it does not look like the person's face. So there must be something going on that is specific to faces there.

In fact, in the study we found that novices with better face recognition skills also drew other subjects (houses) in a way that was judged more faithful to the model than people with poorer face recognition skills. BUT, this does not mean however that one's face recognition skills will determine their ability to draw in a more general way, even if it could provide an advantage initially. Drawing involves a lot of different cognitive skills and training could have more impact on some of these skills than on others (It's an open question!), and help develop many other aspects (technique, style, etc). That's what your experience seems to point to!

Christel, thanks for taking the time to respond to all these comments and thanks everyone for joining the excellent discussion. It goes to show that, as Harvard neuroscientist Margaret Livingstone said, "artists are vision scientists....they just don't often realize it." As I've thought about this study myself, I find myself wondering the most about the question Joe Kulka asked. It doesn't seem possible to me to divide people into categories of experienced vs. novice artists since the skills of drawing and seeing could be manifest at all sorts of levels in different people depending on how much they put a pencil around.

Another thing I wondered about builds on your last comment, Christel. You suggested that someone who has good skills at recognizing faces tends to draw other things well. That make sense especially for things that seem to have faces, like cars or houses. But what about subjects that don't look like faces at all? Do the skills transfer the other direction? For example, would the skills of an artist who is good at, typography translate to faces, or do you need to have specific endowments in that part of your brain to do faces well?

Check out the " Charles bargue drawing course "

Post a Comment