How about having a couple of figures wrestling with a snake, as in the classic sculpture Laocoön? How would a computer deal with the complex muscular dynamics and surface interactions?

How about having a couple of figures wrestling with a snake, as in the classic sculpture Laocoön? How would a computer deal with the complex muscular dynamics and surface interactions?In 3-D computer animation, this problem is sometimes called interactivity, and it’s one of the frontiers that is engaging the finest minds of the business. When Jeanette and I visited some of the post-production special effects houses last fall, like ILM, Imageworks, and Rhythm and Hues—or the CG animation outfits like DreamWorks and Blue Sky, I often asked what is the toughest problem to solve in CGI: Hair? Foliage? Fabric? Water?

On their own, each one of these “holy grail” materials is really coming around. The real challenge is to have these effects interact with each other, to have a couple of figures in loose tunics mudwrestling at the edge of a swamp, or a burning flag flapping in the wind.

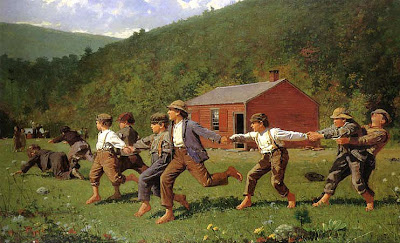

In the painting by Homer above, consider the physics involved in a scene of kids running and holding hands while cracking the whip. Each figure is both self-propelled by the feet, but also externally propelled by the large system of forces delivered through the hands as the momentum builds.

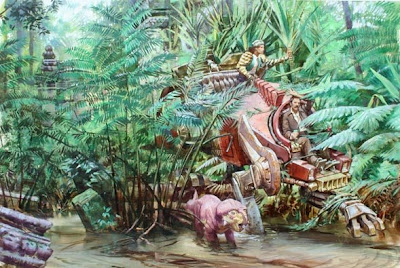

In the painting by Homer above, consider the physics involved in a scene of kids running and holding hands while cracking the whip. Each figure is both self-propelled by the feet, but also externally propelled by the large system of forces delivered through the hands as the momentum builds. I was thinking about maximizing interactivity when I painted this scene from Dinotopia: The World Beneath. A walking vehicle wades through water and weeds. Painting it is no big deal, but realizing it in CGI would take some doing.

I was thinking about maximizing interactivity when I painted this scene from Dinotopia: The World Beneath. A walking vehicle wades through water and weeds. Painting it is no big deal, but realizing it in CGI would take some doing. One figure is pushing on a palmetto (1), while another is brushing away a fern (2), while the leg of the walking vehicle is dragging some plants out of the water (3), while the other leg is splattered with mud and half-submerged (4), while the body of the vehicle is pushing aside another stand of plants.

One figure is pushing on a palmetto (1), while another is brushing away a fern (2), while the leg of the walking vehicle is dragging some plants out of the water (3), while the other leg is splattered with mud and half-submerged (4), while the body of the vehicle is pushing aside another stand of plants.I can only speak with any knowledge as a painter, but I have wide-open admiration for my brother artists and scientists in CGI. Their work excites me because it’s the meeting point of art, physics, mathematics, and materials science.

The advances and challenges in CGI causes us to think about the visual world differently. The geeks behind the scenes who are making the big contribution in this arena don’t get the credit they deserve because their work doesn’t seem as glamorous or comprehensible as the work of the visual development designers.

When you watch the credits roll by on the next CG animated film, give a cheer for the people that figure out the science behind interactive effects.

------

Read about our visits to the movie studios last fall, link.

11 comments:

I have the free 3D tool "Blender" on my PC and have played around with it about a year ago.

I could fairly quickly build a rather complex building - after all it's just geometry.

But then I wanted to move on to organic shapes (characters), their skin and animating them.

I browsed a lot of tutorials, tried it all and finally gave up after realizing it would take me many years of experience to build anythink decent.

So I gave up.

Just drawing things was easier.

And if I draw a book, it's my name only on the cover as opposed hidden in that long list of animators, right?

Why does one job get more credit than others?

In my 'computer consultant' years, the job came with a nice pay and a company car. Some of my colleagues thought we got all that because our job was 'important'.

I always tried not to show anger when I heard that and I calmy asked: "So what is it that makes a nurses' job so much less important than our job that she only deserves about half our pay?".

Unfortunately my move to the art/book world was no improvement.

If you are looking for people who really think they are important, the artist's world is the place to be.

Of my very first professional meeting in the art world, I will always remember the following line: "We are a very prestigious publisher!".

I've never heard a nurse call herselve prestigious...

Interesting...posted the same day as yours.

Worth a look for the 60s viewfinder images!

http://johnkstuff.blogspot.com/2008/08/artistic-graphic-shading-in-cartoons-vs.html

I just saw the Homer painting a few weeks ago at the MFA in Boston.

That's a wonderful painting, and Homer's attention to detail and his command of the human figure is great and very understated. You don't notice all the work he put into it.

In the same gallery is a wonderful painting of a young solder being examined by medical staff. The way he captures moments is fantastic.

Great post!

In classical animation it's usually up to a props/effects designer to come up with model sheets that are used as blueprints for the character animators when it comes to interactivity.

Props are anything that the characters use, hold, or interact with. For instance... a lamppost might easily be part of the background, but if at any point the characters crash their car into it (the car would also be a prop), it becomes a prop and requires a seperate model sheet.

FX are classified as anything that is an environmental effect that interacts with the moving props or characters. These are all typically characterized by the fact that they have dynamic volumes; a character should remain the same height and weight, regardless of where he moves, but things like cast shadows, water, flames... their volume and/or surface area changes depending on what's going on around them.

At least in the world of televison animation, 2D FX animation design is becoming rarer every passing year; leaving the onus on the character designer to figure out how a candle flame would react to a gust of wind, or how a futuristic robot's time-travel effect would look.

It's a very interesting specialization, though there's not a lot of information

Eric, Thanks for that great link to John K. Stuff. A refreshing rant, and I loved those 3-D viewmaster images. Didn't know they existed.

Erik, you always bring up ideas that I think about all day after reading your comments. Prestigious nurses, hmmmm.

Jeff, you're lucky to see those Homers and other paintings in Boston. I love Homer, too. He's almost never flashy, but for some reason most of his best images are unforgettable.

Ripsey, thanks for the inside look at how the jobs are divided up. I can see why it's hard to get the whole impression in 3-D CG animation to be an organic whole, rather than a collection of separate elements.

The other thing about Homer was that he had what I would call the artistic equivalent of perfect pitch.

He never missed. Everything I have seen of his is spot on in values and effect. Even when he pushed it.

There are a few watercolors from his trips to Florida and the Caribbean that are amazing. In one he used a rough paper and utilized to create the effect of a stucco wall. Very under rated artist in my view.

Also in this show are some fantastic charcoal studies of his fishing paintings which are amazing examples of quick yet accurate working drawings.

Dear Mr. Gurney,

My name is Mariana Moreno, I'm a Mexican comic book artist, I belong to a comic book studio's creative team named Ka-Boom! Studio here in our country.

Probably you must already have read this kind of comments a thousand times, but I just couldn't resist to write to you.

I just wanted to express my deepest admiration for your work, it is absolutely inspiring. I believe there are few illustrators who can portrait such a strong feeling on their work like you.

Also, I wanted to thank you for the artistic advise you post on this blog. The fact that an artist like you shares his knowledge with other colleagues is worth of admiration and respect.

On your dinosaur art, did you have any influences from paleoartists Mark Hallett or Raul Martin? They are outstanding artists too.

By the way, at the Dinotopia official site, at the FAQ section, the fourth picture, was that paleontologist Jack Horner with you? It must have been wonderful to work with him!

I'm sorry for such a large comment, you must be very busy, I just wanted to ask for your permission to include you in my blog's contact list. If you wish you can visit it at:

sketchbookdemm.blogspot.com

And you're also invited to visit our website at: www.ka-boom.com.mx

Thanks for your time, I hope we can stay in touch.

Greetings from Mexico!

Thank you for this post. At a time when the popular sentiment is that CGI is bad art created by soulless machines and technicians it is refreshing that someone has noticed that there may be another viewpoint. I am biased of course, I am a visual effects artist.

The question of interactivity is an interesting one. Most of the examples you present are dynamic simulation problems and more and more brilliant algorithms are being developed all the time that enable artists to do more than ever before. The flip side of this is the practical application of these simulation technologies. An example might help me explain what I mean.

The most recent film that I had anything to do with that's out in cinemas is Hellboy 2; I worked on the stone giant that climbs out of the ground - he's in the trailers for anyone who's interested but doesn't want to see the movie at the cinema. A core team of four of us did the effect and it took us a year, just to give you an idea of how labour-intensive this kind of work is.

As the giant hauls himself out of the earth there is a huge amount of interaction required: the giant himself has to crack and shatter as the stresses and strains pull him apart, the earth on top of him has to buckle and rip and there is a huge amount of loose soil and stone that gets displaced. We simulated elements for all of this but we did it as a series of vignettes. What I mean by this is that we ran simulations on specific parts of the giant which were triggered to begin simulating at certain moments. So when he smashes his arm down, we trigger a sim to begin on that arm so that stones will break off and cascade down. We even designed the system so that we could keep elements of a sim that we liked and just redo parts we didn't care for until we had a whole performance that worked. My point is that even when using physically based simulations it is possible to be artistic and creative so that the focus is on making an aesthetically pleasing and narratively functional sequence rather than on just replicating exactly what would happen "in reality".

Once the CG is rendered, it is then composited into the plates (the background of Northern Ireland is a painting we did by the way) and a lot of real footage of dust and earth is layered in with the CG to add texture and extra complexity.

So it's not only the technology itself but also the way it is leveraged and how it can be controlled that makes it interesting.

Hi James,

I realise this doesn't directly touch the subject of the topic, interactivity. Nevertheless, I thought it could be intresting to bring it to your attention if you are intrested in advanced cg.

http://www.awntv.com/videos/image-metrics-emily-project

Gracias, Mariana. You are so simpatica. Yes, I admire Mr. Hallett's and Mr. Martin's work--they are the real thing. And yes, that's Jack Horner with me in that photo!

Mr. Atrocity, thanks for explaining how you did that incredible Hellboy sequence. If I understand you correctly, the simulation part of it is what the math/physics model generates automatically, and yet you can still animate and tweak those elements to make the artistic statement, right?

By the way, the life cast sequence on your blog is amazing!

I suppose first I ought to get the obligatory hi, I love your work! fan comment out of the way, so there there you go. ;)

Very interesting post, though. I'm not heavily into working with computer rendered graphics myself, but I certainly see enough of it with as much of a video game and Japanese animation geek that I am. I think part of the reason the people doing the grunt work, so to speak, don't get as much credit though is due to the fact that there's typically so many people working on any given project. It's similar to how with traditional cel animation, there could be (and often were) literally dozens of people drawing and painting the cels for every individual frame created for the final product. It's much more difficult to figure out how to credit a large team than just one individual artist, I imagine. Also, at least in traditional animation, labor tended to be divided out in a way that meant most of the artists were simply tracing lines with slight variation or effectively painting by number. All the 'important' work went to key animations, who of course then get their own separate spot in the credits. Although back to CGI, there's also the programmers who write the code behind the massive rendering engines that the animators then use to make their finished work, which is also somewhat overlooked.

Though while I appreciate the work that goes into it, I have to say a lot of the wholly-CGI films I've seen previews of in the past few years are unfortunately somewhat underwhelming- much better work has been done on other films, video games, and general animation before, thus raising the bar on quality. If you take a look at the rendering and interactivity and attention to detail in some of the newest video games or high-budget Japanese animation (I highly recommend Ghost in the Shell for an excellent example of what's possible with CGI) the tools and techniques to generate these things definitely already exist, but aren't always being utilized to their full potential.

Post a Comment