Here's a philosophical question:

Let's imagine a person born blind had learned to distinguish shapes by the way they feel. If you could surgically bestow sight on that person, would he or she correctly identify those same shapes by sight alone, without recourse to touch?

People argued about this question for centuries. It is a hard one to test, because it's so rare to find experimental subjects. There aren't many people who start with total congenital blindness and later attain full vision.

In recent years, Pawan Sinha, of MIT, was able to find five individuals who met the requirements. They started out with only the ability to distinguish between light and dark. After a surgical procedure gave them the ability to see, they looked at a selection of forms with which they were already familiar by touch.

Although they could readily differentiate one shape from another visually, they could not transfer their tactile knowledge into the visual realm. They could not connect touch and sight. Their guesses were no better than chance. The answer to Molyneaux's problem was a decisive "no."

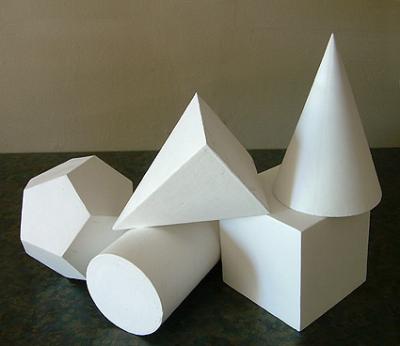

|

| Sculpture by Carpeaux |

This problem has relevance for artists. Several art theorists, including Harold Speed, have put great stock in the differences between the sense of touch and the sense of sight.

Many artists now develop their visual skills to a high level, often exclusively through a computer interface, without having the opportunity to touch the objects they draw or paint.

I've always believed that any chance we have to feel, touch, smell, or hear something that we're drawing will make us draw a more convincing representation of it. If you've danced the Charleston, you'll animate it better. If you've tightened the cinch on a Western saddle, you'll paint a better cowboy.

So the problem is not just experiencing the world through all our senses, but integrating those senses with each other. One thing that helps me when I set out to do a plein-air painting is to walk around the subject and check it out first before diving into the preliminary drawing.

-----

You might enjoy these previous posts:

Can Blind People Draw?

Seeing With the Hands

Touching Art at the Prado

Blindsight

Molyneaux's problem on Wikipedia.

11 comments:

Great post! I think you've pointed out very specifically one reason that working exclusively from photographs can, and often does, result in inferior work because there's never even a visual connection to the subject, much less a tactile one. It's an interesting problem for those of us who are wildlife artists who only paint what we have seen ourselves in the wild (many don't). We have the visual input but there are a variety of obvious problems in attaining the tactile experience.

I find that when drawing people from life, I rely a lot on knowing what it feels like to be a person, as well as what it feels like to touch a person. When drawing animals, the farther they are from me on the tree of life, the more challenging it is to physically empathize with them. I can sort of relate to a dog or a cow, maybe even a fish, but once we get into exoskeleton territory it's a whole different game. What does it feel like to be a bee? How could that feeling be conveyed through visual media?

MDMATTIN, good point to think about what it feels like to be on the inside of a person as well as on the outside.

SFOX, I suppose a wildlife artist can benefit from hanging around and dealing with farm animals. Feeling the horns on a domestic goat helps me imagine a wild goat. Also, it's amazing how many early wildlife artists were hunters, or at least dealt with real animals, alive and dead.

The writer Diana Gabaldon has said that the best way to bring a written scene to life is to include descriptions of at least three senses, as for example the smell of cooked food, the clatter of utensils, and the sight of a full plate. --Jane (I'm signing this because this thing always signs me up as Anonymous)

Reminds me of the fable about the four blind men and the elephant. Just a little.

You make an interesting point about getting to know what might be termed 'the next best thing', James. Sounds a little like the comparative anatomy and extrapolation in palaeoart. Do tactile or up-close encounters with living animals (beyond photo reference and the like) help you with that? Is that part of the role of your clay maquettes too?

I couldn't help but apply this to your many awesome maquettes-to-finished-works process, James! And I, too, love all the sensory experiences and weird goings on that happen (and inspire) en plein air! Really interesting!

at the art student's league all my realist painter teachers recommended modeling the head in clay to really understand the planes and get a sense of depth. I have always found that sculptures are great draftsmen as well...

I think ted seth jacobs used to recommend touching the objects you were painting as well. obviously this can't/shouldn't be done with human models in atleirs..

I love this post, and I agree that having touched an object gives an artist a better feel for that object. I grew up with a Tennessee Walker horse as a companion. I was always brushing her and running my hands over the newly brushed areas. I'm convinced that early experience prepared me to draw horses from memory - muscle memory, if you will. When I taught drawing, I encouraged (made it part of their final grade)them to go up and touch the still life objects they were drawing.

I wonder if they would improve if they were trained before hand. We know it's hard even for people who can see to keep an accurate 3d representation of an object in their head, but if they could be trained to do that while still blind (and there are blind artists that can, I forgot his name, but there was one in particular I remember from a documentary or something that could accurately draw 3d forms he felt, even like a large building), I feel like they would be able to recognize the objects once they could see. Too bad there's so few opportunities to test it. Maybe someday when we develop proper bionic eyes.

It reminds me of Nicolaides book, it talks about using all of your senses to draw naturally. Being able to feel the form in your mind. Another book by ron tiner "Figure Drawing Without a Model", he talks about when drawing the model that you should strongly feel the part on yourself that you're drawing of the model. Like say you're drawing the arm you increase your awareness of your arm.

Post a Comment