The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has released a fascinating hour-long video relating to its "John Singer Sargent Watercolors" exhibition. The video is a conversation between co-curator Erica Hirshler and Sargent's grandnephew Richard Ormond, who probably knows more about Sargent than anyone else on the planet. At 48 minutes into the hour Mr. Ormond shares some insights into photos of Sargent's studio. (Link to video) The exhibition will continue through January 20, and there's an excellent catalog of the show.

Tuesday, December 31, 2013

Sargent watercolor discussion

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has released a fascinating hour-long video relating to its "John Singer Sargent Watercolors" exhibition. The video is a conversation between co-curator Erica Hirshler and Sargent's grandnephew Richard Ormond, who probably knows more about Sargent than anyone else on the planet. At 48 minutes into the hour Mr. Ormond shares some insights into photos of Sargent's studio. (Link to video) The exhibition will continue through January 20, and there's an excellent catalog of the show.

Monday, December 30, 2013

Questions about Black, Part 4 of 4

The last question is deceptively simple.

Is black a color?

The answer is no and yes, depending on how you mean the question, and what you mean by "color."

The "No" answer:

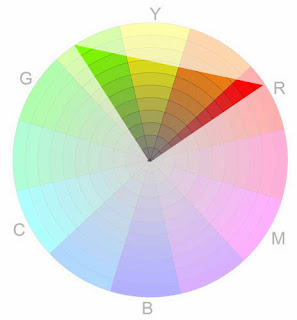

If you're talking about how the abstract concept of black fits into the infinite range of hues and chromas within the three-dimensional color universe, you might argue that it doesn't really belong with the others at all, because by definition it has no hue and no chroma. Black is not only the absence of color; it's even the absence of light.

The "Yes" answer:

Looking at the question another way, the answer is yes. Black does have its place at the base of the 3-D chart of the color universe, where hues are arrayed around the outside, chroma (saturation) decreases toward the vertical center line, and value goes up or down with height.

Black has its own color swatch just like all the others. It sits at the zero point of value, the extreme pole beneath all dark colors. It's like the lowest note on the piano, one that you can include in a composition if you want to. In yesterday's post, we explored the arguments for and against using pure black in a painting, and just how pure that black pigment can be.

Just as black is a color, white and all the gray tones are colors, too, since each has its own location within the 3D color universe. They are like other keys on the piano, each a legitimate option that an artist may wish to include.

Just as black is a color, white and all the gray tones are colors, too, since each has its own location within the 3D color universe. They are like other keys on the piano, each a legitimate option that an artist may wish to include.

The surprising thing is that black, white, and the gray notes can function in a color scheme in such a way that they don't seem neutral at all. If you choose a gamut with two bright colors plus neutral black (and tints of black), the black suddenly becomes a very distinct subjective color. In the case of the color scheme at right, it would appear blue.

And this is where the "yes" answer becomes more than academic. Black really is a color that can be a core component of a luminous color scheme.

I demonstrate how this principle works in this video, which perhaps a lot of you have already seen. (Direct link to video)

In the end, it's good for beginning painters to be aware of the hazards of black. Many teachers rightly warn against using black carelessly, because it can deaden mixtures or kill the mood or the illusion of light in a painting. It's good to know how and when to mix your own black from other colors. But if you use black consciously, it deserves to be a valued part of any painter's toolkit.

Part 3: Using black in a painting

Part 4: Is Black a color?

Get my book "Color and Light" signed from my website or from Amazon .

.

Is black a color?

The answer is no and yes, depending on how you mean the question, and what you mean by "color."

The "No" answer:

If you're talking about how the abstract concept of black fits into the infinite range of hues and chromas within the three-dimensional color universe, you might argue that it doesn't really belong with the others at all, because by definition it has no hue and no chroma. Black is not only the absence of color; it's even the absence of light.

|

| Munsell Color Solid from Munsell.com |

Looking at the question another way, the answer is yes. Black does have its place at the base of the 3-D chart of the color universe, where hues are arrayed around the outside, chroma (saturation) decreases toward the vertical center line, and value goes up or down with height.

Black has its own color swatch just like all the others. It sits at the zero point of value, the extreme pole beneath all dark colors. It's like the lowest note on the piano, one that you can include in a composition if you want to. In yesterday's post, we explored the arguments for and against using pure black in a painting, and just how pure that black pigment can be.

Just as black is a color, white and all the gray tones are colors, too, since each has its own location within the 3D color universe. They are like other keys on the piano, each a legitimate option that an artist may wish to include.

Just as black is a color, white and all the gray tones are colors, too, since each has its own location within the 3D color universe. They are like other keys on the piano, each a legitimate option that an artist may wish to include.The surprising thing is that black, white, and the gray notes can function in a color scheme in such a way that they don't seem neutral at all. If you choose a gamut with two bright colors plus neutral black (and tints of black), the black suddenly becomes a very distinct subjective color. In the case of the color scheme at right, it would appear blue.

And this is where the "yes" answer becomes more than academic. Black really is a color that can be a core component of a luminous color scheme.

I demonstrate how this principle works in this video, which perhaps a lot of you have already seen. (Direct link to video)

"Questions about Black" Series

Part 2: Mixing your own blackPart 3: Using black in a painting

Part 4: Is Black a color?

Get my book "Color and Light" signed from my website or from Amazon

Labels:

Color

Sunday, December 29, 2013

Questions about Black, Part 3 of 4

In yesterday's post, we explored the whys and hows of mixing your own black. But there are still a lot of unanswered questions about black.

But you can also crush the blacks and then raise them into a color range to add a faded film, or "Instagram" look, which is also stylish right now. The still above is from a demo reel by Sunday Studio. This effect can easily be achieved in a painting as well.

Is black a color?

Do some kinds of artists use black more than others?

Yes. Designers, cover artists, comic artists, and poster designers use black a lot because of its simple graphic power. Above is a cover by Coles Phillips (1880-1927), which uses black as a clever design element.

Portrait painters and still life painters often use black on the palette. Landscape painters are most likely to ban black from the palette.

Portrait painters and still life painters often use black on the palette. Landscape painters are most likely to ban black from the palette.

Why? So should landscape painters take black off the palette?

Well, I'm not one to make hard and fast rules, because there are always exceptions. There have been artists who have used black effectively in landscape. Rowland Hilder (1905-1993) did the watercolor above. He often started with black ink, and I think it works well for him here. Andrew Wyeth also used black effectively, because he was after a starkness and melancholy and absoluteness that black was perfectly suited for.

The reason a lot of landscape painters in oil leave black off the palette is to remind them that there is illuminated atmosphere between them and everything in the scene. Our eyes can trick us into thinking that an open window across the street is pitch black, when really it's shifted up from black quite a bit. You can see this by holding up a lens cap or some other shaded black object next to the thing you think is black in the landscape. I think it's reasonable to say that beginning landscape painters in oil should have a lot of experience painting without black—or for that matter without brown—until they know they can mix any color they see from a set of highly chromatic "primary" pigments.

What are the pros and cons of using a note of pure black in the painting?

The reason you might need black on your palette is that it will give you just a little extra punch. If I'm doing a realistic painting, I work under the philosophy that black should be reserved for rare and special parts of the picture. I mentioned this in a post called "The Separateness of Black."

I tend to agree with John Ruskin. He said in his book "The Elements of Drawing:" "You must make the black conspicuous. However small a point of black may be, it ought to catch the eye, otherwise your work is too heavy in the shadow. All the ordinary shadows should be of some colour,— never black, nor approaching black, they should be evidently and always of a luminous nature, and the black should look strange among them; never occurring except in a black object, or in small points indicative of intense shade in the very centre of masses of shadow."

If I might add to that, I would say that pure white or pure black can destroy the subjective color atmosphere of a scheme, like pressing the auto white balance on a camera, or pressing the "Auto Levels" button in Photoshop. Above is a Sanford Gifford landscape with its subjective warm gamut intact. Note that its lights stay clear of pure white and its darks stay clear of black. Below is the same painting given the auto levels treatment, which harms the poetic effect. Perhaps that's one reason why Rubens said, "It is very dangerous to use white and black."

How can one get the purest black?

Pure, absolute black is beyond the reach of any single pigment. The darkest value you can get with a surface is probably black velvet.

Any black pigment reflects a certain amount of light, depending on how it's painted, how it's varnished and how it's lit. The black passages in my painting of Moche prisoners for National Geographic, above, reflect a fair amount of light, even though they're painted with pure ivory black. That's just because of the brushstroke textures are giving off a lot of diffuse reflection.

Some artists achieve very dark blackish colors by glazing, sometimes by glazes of different colors laid over each other in a single passage. If it's varnished and lit correctly, this method for achieving dark colors can yield very rich and mysterious darks.

Pure, absolute black is beyond the reach of any single pigment. The darkest value you can get with a surface is probably black velvet.

Any black pigment reflects a certain amount of light, depending on how it's painted, how it's varnished and how it's lit. The black passages in my painting of Moche prisoners for National Geographic, above, reflect a fair amount of light, even though they're painted with pure ivory black. That's just because of the brushstroke textures are giving off a lot of diffuse reflection.

Some artists achieve very dark blackish colors by glazing, sometimes by glazes of different colors laid over each other in a single passage. If it's varnished and lit correctly, this method for achieving dark colors can yield very rich and mysterious darks.

What is meant by “crushing blacks?”

Crushing black is a technique of digital color adjustment in photography, film, and video where you clip off the low end of the histogram to add contrast, simplicity, or a "comic book" look (300, above). It's very popular in modern movies. National Geographic has done this with its photos for decades, so much so that photographers from other magazines joke derisively about "National Geographic Black."

But you can also crush the blacks and then raise them into a color range to add a faded film, or "Instagram" look, which is also stylish right now. The still above is from a demo reel by Sunday Studio. This effect can easily be achieved in a painting as well.

Is black a color?

Whew, I'm too tired to answer that right now. Let me extend one more day and answer it tomorrow. If you have another question about black, ask in the comments, and I'll try to get to it tomorrow.

Part 3: Using black in a painting

Part 4: Is Black a color?

Get my book "Color and Light" signed from my website or from Amazon .

.

"Questions about Black" Series

Part 2: Mixing your own blackPart 3: Using black in a painting

Part 4: Is Black a color?

Get my book "Color and Light" signed from my website or from Amazon

Saturday, December 28, 2013

Questions about Black, Part 2 of 4

|

| Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (1841-1920) |

Now let's consider some other common questions about black.

How can an artist mix their own black?

You often hear of artists mixing their own blacks out of other colors. I often mix a black-like color out of two dark complementary colors, such as ultramarine blue plus raw umber, or viridian plus permanent alizarin. The resulting color may not be as dark as a tube black. Sometimes I even use two colors which don’t mix a very dark black at all, such as cobalt blue and cadmium red. But getting the darkest color is not the goal.

Why use these mixed blacks?

It's the variations and imperfect mixtures I'm after. I like using these composite blacks because as I mix them, I'm more aware of their chromatic properties, their color character. Generally as I mix them, I set aside some mixtures that lean more toward one side (such as red) and other mixtures that lean more to the other (such as green). Black is by definition the darkest possible reflective pigment, and the closest you can get to the absence of chroma or hue. I often like to keep my darks from going all the way to black so that they can include some particular color identity to them as they enter into the darker regions of value.

It's the variations and imperfect mixtures I'm after. I like using these composite blacks because as I mix them, I'm more aware of their chromatic properties, their color character. Generally as I mix them, I set aside some mixtures that lean more toward one side (such as red) and other mixtures that lean more to the other (such as green). Black is by definition the darkest possible reflective pigment, and the closest you can get to the absence of chroma or hue. I often like to keep my darks from going all the way to black so that they can include some particular color identity to them as they enter into the darker regions of value.

This way of thinking is analogous to a lighting designer using an LED wash light or a set of three different colored instruments (red, green, blue) to create a mixed white light on a subject, rather than using a single "white" light like a halogen bulb. (I put "white" in quotation marks because as every photographer knows, every white light source has its own unique color properties, just as every black pigment inevitably does.) Using colored lights lends chromatic energy to the terminator between light and shadow and to the edges of the cast shadows. In the same way, using a mixed black encourages you to find dynamism in the dark passages in your painting.

or a set of three different colored instruments (red, green, blue) to create a mixed white light on a subject, rather than using a single "white" light like a halogen bulb. (I put "white" in quotation marks because as every photographer knows, every white light source has its own unique color properties, just as every black pigment inevitably does.) Using colored lights lends chromatic energy to the terminator between light and shadow and to the edges of the cast shadows. In the same way, using a mixed black encourages you to find dynamism in the dark passages in your painting.

" which is a mixture of quinacridone red and phthalo green, rather than the usual carbon or iron oxide ingredients. But to me this defeats the purpose of mixing your own black, because the variegated mixtures are what you want.

" which is a mixture of quinacridone red and phthalo green, rather than the usual carbon or iron oxide ingredients. But to me this defeats the purpose of mixing your own black, because the variegated mixtures are what you want.

Can you buy mixed blacks in a tube?

As Connie Nobbe pointed out in yesterday's comments, Gamblin offers a black oil color called "Gamblin chromatic black |

| Bonnat Portrait of Barye |

But aren't there times when you want your darks to be neutral and undynamic?

Yes! Sometimes you want your black to look black, and your tints of black to look gray. This is especially true when you're painting a somber portrait of someone wearing black clothes. I think of the Dutch painters, of the Spaniards like Velazquez, or the French painters they influenced, like Bonnat. I'm not really sure about the one at left because I haven't seen it, but I would bet he used black to paint Barye's coat. It would look sort of fruity if there was a whole lot of color dynamics going on.

Do you have black on your full-color palette?

This reminds me of a story. I used to know a girl in art school who kept a pneumatic boat horn in her desk. She always had it ready to blast into the phone in case she got a heavy breathing crank caller. She didn’t need to use it often, but she was glad to have it handy when she did need it. My tube of black paint is like that boat horn. It’s there if I need it.

Perhaps you have heard the famous story where Sargent, borrowing Monet's palette, complained about the lack of black. Despite that story, Sargent's paintings, especially his watercolors, are notable for their interesting color identity in the dark-value passages.

Tomorrow I’ll talk more about the aesthetics—and hazards—of using black, not just in portrait and landscape painting, but in photography and film, and I'll consider the question: Is black a color?

"Questions about Black" Series

Part 2: Mixing your own blackPart 3: Using black in a painting

Part 4: Is Black a color?

Get my book "Color and Light" signed from my website or from Amazon

Friday, December 27, 2013

Questions about Black, Part 1 of 4

|

| Nikolai Yaroshenko (1846-1898) The Student |

“Is black part of your palette when mixing colors? Many artists state that they never use black but I don't understand if they mean that they don't like using it straight out of the tube on to the canvas or if they banned it even as a mixing component from their palette altogether.”

Hi, Kostas,

Good question and comment. Let me try answering them, and I'll ask a few more questions. I will do this as a three-part series.

Can you use black to darken a color?

Black is a very useful color. However many artists will tell you that if it is used to darken all the colors, it can "muddy" a color scheme. They are right. That's because black pigment will reduce chroma too quickly as it darkens or "tones" a color. Rather than looking like a darker version of the color, a color mixed with black will be both darker and a lot grayer, which can give the picture an unpleasant dullness. Another problem with black in mixtures is that it will often shift a hue toward another hue. For example, yellow turns green when mixed with black.

David Briggs explains these phenomena on his excellent website HueValueChroma. In this diagram from his page on mixing with black, he compares how a mixture of permanent alizarin and white (A) changes as it is darkened by black, compared to a line of uniform saturation (B). The pigment mixtures are plotted using software from the website couleur.org.

How do you darken a color without using black?

To avoid that problem, painters use a variety of colors to darken or tone other colors. Usually these toning colors are pigments that appear dark right out of the tube, often because they are transparent. Ultramarine, the phthalo blues and greens, burnt umber, and permanent alizarin crimson can all be useful for toning other colors. By using these colors to darken your mixtures, you can control the chroma and, if you need to, pull it away from dullness, or just give it more interesting variations of chroma as the colors get darker, so that the dark realms of your colors aren't all monochromatic.

What are the uses for black?

Despite its tendency to be a color-mixing crutch for beginners, black has its uses. I love black pigment. I have a tube of black in all the media I paint with: oil, casein, gouache, and watercolor. I use black pigment most often when I'm painting in grisaille with just black and white, or in a super-limited palette of black, white, and another color. I also use it if I want an accent of the darkest possible value (more about that on Sunday).

Are all black pigments the same?

No. In watercolor, it's fun to experiment with different kinds of black: bone black, lamp black, Mars black. The pigment called "ivory black" used to be made from elephant ivory. Since that is now unavailable, some paint makers create ivory black by burning and grinding up fragments of mammoth ivory from Russia, which is legal to use. Each kind of black has different qualities of texture and chroma. If you get a couple of different blacks, you can play with them and compare them by painting them in a thin glaze, tinting them with white, and mixing them with other colors.

"Questions about Black" Series

Part 2: Mixing your own blackPart 3: Using black in a painting

Part 4: Is Black a color?

Get my book "Color and Light" signed from my website or from Amazon

Labels:

Color

Thursday, December 26, 2013

Raffaëlli's Ragpickers

Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850 – 1924) was a French realist artist who painted portraits of the ragpickers.

Ragpickers, also called "rag and bone men" or "chiffoniers" in French, collected scraps of discarded cloth, bones, metal and and other unwanted refuse from the streets of Paris. They lived in a northern district of the city and worked at night.

They carried a large bag or a basket on their backs. In one hand they carried a cane-like stick with a sharp pointed end, and in the other they held a lantern.

According to Shirley Fox, a young art student in Paris, "The appearance of some of these birds of the night, as they flitted about from place to place, was most picturesque. Some of them were withered and wrinkled old men and women who looked more like animated mummies than human beings."

According to Shirley Fox, a young art student in Paris, "The appearance of some of these birds of the night, as they flitted about from place to place, was most picturesque. Some of them were withered and wrinkled old men and women who looked more like animated mummies than human beings."

Citizens would throw garbage out their window onto the streets, and the rag pickers would sort through it, taking anything they could resell.

Striving to improve sanitation in France, an 1883 law required people to throw their trash into receptacles, which the ragpickers were allowed to dump out and sort through.

Striving to improve sanitation in France, an 1883 law required people to throw their trash into receptacles, which the ragpickers were allowed to dump out and sort through.

But these arrangements eventually changed the habits of the ragpickers, who were replaced by the more familiar garbage collectors and recycling men of our own era.

The rags were a raw material for making quality paper. Bones were used for knife handles and toys, and the grease taken out of them was used for making soap.

Painting such poor people was a preoccupation of some of the realist painters.

Eduoard Manet painted a chiffonier. Whether such subjects were worthy for art divided the painters who came to be known as Impressionists, some of whom were sympathetic to such commonplace subjects. Others wished to exclude them from exhibitions.

The American painter Thomas Waterson Wood (1823-1903) also painted a ragpicker.

Striving to improve sanitation in France, an 1883 law required people to throw their trash into receptacles, which the ragpickers were allowed to dump out and sort through.

Striving to improve sanitation in France, an 1883 law required people to throw their trash into receptacles, which the ragpickers were allowed to dump out and sort through.But these arrangements eventually changed the habits of the ragpickers, who were replaced by the more familiar garbage collectors and recycling men of our own era.

Wednesday, December 25, 2013

Alphonse Mucha's Hearst magazine covers.

|

| Alphonse Mucha Hearst magazine cover |

Best wishes to all the Journeyers for a Happy Christmas or whatever midwinter holidays you celebrate.

|

| Alphonse Mucha Hearst magazine cover, December |

Labels:

Golden Age Illustration

Tuesday, December 24, 2013

The Angels of Christmas

|

| 2013 Christmas pageant, painted during the performance in watercolor and gouache. |

May the angels of Christmas bring courage and and serenity to you all.

Monday, December 23, 2013

Spook-a-Rama

On my first visit to Coney Island in 1981, I sat down outside the Spook-a-Rama ride and pulled out my sketchbook.

Giant green spiders and one-eyed statues were hanging over the spot where I was sitting, but I liked it because I had a good view of the ticket booth.

The ticket man leaned into his microphone. "Spook-a-Rama! It's the big ride!" he said. "Everybody ride!"

Nobody was buying tickets, so I gave the guy some customers.

----

This drawing appeared in my 1982 book The Artist's Guide to Sketching

Other imaginative sketching on the blog:

Sunday, December 22, 2013

Big Cat Sketching Safari

Paleoartist Mauricio Anton helped to organize a safari to northern Botswana to sketch big cats in the wild. He filmed and edited a video about it, and he wrote the music, too. (Direct link to video)

He'll be doing the safari again if you're interested in joining in.

Mauricio Anton has written and illustrated several books, including Sabertooth (Life of the Past)

Behind-the-scenes video about the art of bird dioramas

The American Museum of Natural History has just created some new videos about the making of the dioramas in the bird hall. In this one, exhibition artist Stephen Quinn spotlights bird painters Louis Agassiz Fuertes and Francis Lee Jaques, as well as taxidermist David Schwendeman, who was able to present the birds in lifelike flying positions.

If you like this one, check out the other video: "Birding at the Museum: Frank Chapman and the Dioramas" And on a related note, Michael Anderson has published Chapter 11 of his online bio of diorama artist James Perry Wilson.

Stephen Quinn is also the author of Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History

Labels:

Animals

Saturday, December 21, 2013

Rockwell Biography Criticized by Family

Thomas Rockwell, Norman's son, blasts the inaccuracies, falsehoods, and innuendos in Deborah Solomon's recent biography "American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell " in a 45 minute long interview on WAMC public radio.

" in a 45 minute long interview on WAMC public radio.

Solomon's biography suggests that Rockwell's art was driven by feelings of pedophilia and homosexuality, and that his self-absorption led to the deaths of family members.

Thomas said that the biographer spent only two or three hours interviewing him in a diner and gave him no opportunity to respond about inaccuracies in the manuscript. This is unfortunate, as Thomas is the person who worked most closely with Rockwell on his famous autobiography . "This is a huge literary snow job," he says.

. "This is a huge literary snow job," he says.

N.R.'s granddaughter Abigail characterizes the book as "salacious lies in the guise of a well-researched book."

Thomas said that the biographer spent only two or three hours interviewing him in a diner and gave him no opportunity to respond about inaccuracies in the manuscript. This is unfortunate, as Thomas is the person who worked most closely with Rockwell on his famous autobiography

N.R.'s granddaughter Abigail characterizes the book as "salacious lies in the guise of a well-researched book."

Wake Forest University professor Patrick Toner also dissects the book's portrayal of Rockwell and challenges Solomon's scholarship in his detailed online article "False Portrait." Toner says that Solomon's arguments "are deeply flawed, and she has a pronounced tendency to either distort or ignore evidence to the contrary of her claims."

I haven't read the book, but I read the biographical article that Ms. Solomon wrote in Smithsonian. Rather than being a humanizing portrait of Rockwell, I found it to be full of inaccuracies and innuendos, and I was surprised it got by Smithsonian magazine's fact-checkers.

I believe the Norman Rockwell Museum made a mistake in endorsing the book and hosting its launch. While it is laudable for the museum to provide a forum for a variety of views on Rockwell, it's also essential for them, as the nexus of Rockwell scholarship, to set the record straight when false or misleading claims are made about the man, especially when those claims have been uncritically accepted by the mainstream press. I hope the museum will make a statement clarifying its position and correcting the record.

No one wants a sanitized image of Rockwell, but we do want a truthful one.

I believe the Norman Rockwell Museum made a mistake in endorsing the book and hosting its launch. While it is laudable for the museum to provide a forum for a variety of views on Rockwell, it's also essential for them, as the nexus of Rockwell scholarship, to set the record straight when false or misleading claims are made about the man, especially when those claims have been uncritically accepted by the mainstream press. I hope the museum will make a statement clarifying its position and correcting the record.

No one wants a sanitized image of Rockwell, but we do want a truthful one.

----

Further reading

• In Huffington Post, Sherman Yellen, who knew Rockwell, describes Solomon's portrait as a "distorting carnival glass view of Norman Rockwell"

• Patrick Toner's online rebuttal article "False Portrait.

• In a New York Times review of the book, Garrison Keillor characterizes Rockwell more sympathetically and questions Solomon's sexualized portrait.

Further reading

• In Huffington Post, Sherman Yellen, who knew Rockwell, describes Solomon's portrait as a "distorting carnival glass view of Norman Rockwell"

• Patrick Toner's online rebuttal article "False Portrait.

• In a New York Times review of the book, Garrison Keillor characterizes Rockwell more sympathetically and questions Solomon's sexualized portrait.

• Solomon's interview tactics have been challenged previously by others, including This American Life's Ira Glass.

• Why Solomon's Q&A column was axed at the New York Times

• Solomon's disastrous public interview with Steve Martin

• Why Solomon's Q&A column was axed at the New York Times

• Solomon's disastrous public interview with Steve Martin

Labels:

Golden Age Illustration

Friday, December 20, 2013

Sculpting a Croc in Three Minutes

Sculptor Gary Staab created this short video showing how he sculpted and cast a saltwater crocodile. The croc will be part of an exhibition called "Crocs -- Ancient Predators in a Modern World" (link to video)

Gustaf Tenggren blog

Lars Emanuelsson, who runs a website on Tenggren now has a blog. He is working on a book about Tenggren that will be released next year.

Labels:

Golden Age Illustration

Berlin, 1900, captured on film.

Crisp, colorized film footage shows bustling street life in Berlin and Munich in 1900 and 1914. (Direct link to video)

Note: miniature car at 2:14,

kids doing somersaults at 2:36,

steam-powered vehicle in the upper right of the shot at 3:07,

guy working a camera at 3:10.

Thanks, Christian.

Thursday, December 19, 2013

Cellist Vladimir Morgovsky

|

| Cellist Vladimir Morgovsky by James Gurney |

Labels:

Watercolor Painting

Wednesday, December 18, 2013

Interview on Urban Sketchers

Mark Taro Holmes just released the following interview on the group blog Urban Sketchers.

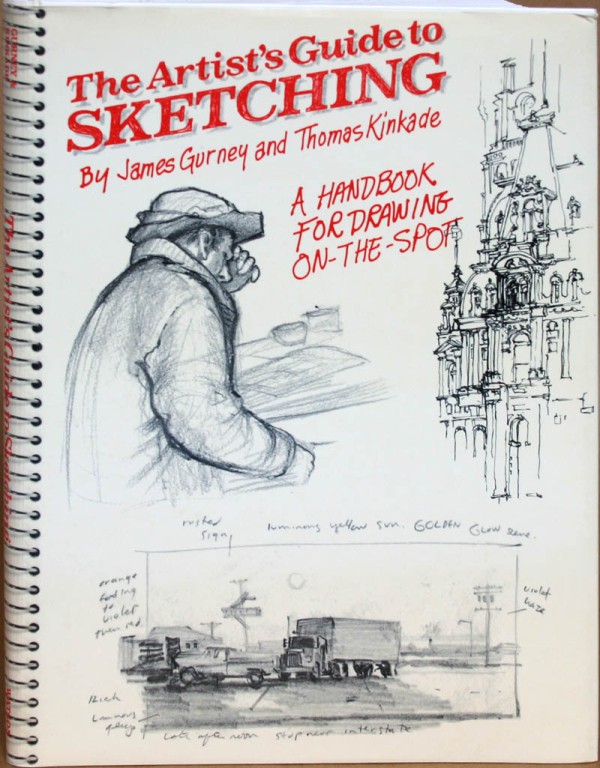

MTH: I asked around if any of our sketchers had a question for you. Here’s one that’s a great opener from Cathy Johnson of Missouri: "I've loved James Gurney since his very first book, back in the 80s; The Artist's Guide to Sketching, with Thomas Kinkade (yes, that Kinkade--they took different paths!) Two young men taking off to sketch across America...it's delightful! "

J.G: Thanks, Cathy! I love your work too, ever since I first saw it in An Illustrated Life.

Tom Kinkade and I were assigned together as freshmen roommates at UC Berkeley when we were both 17 years old. Over the years we went on a lot of sketching adventures together. I knew him long before he became the “Painter of Light.”

We both went to the same art school, but we left after a couple semesters because we started getting jobs, and the school wasn’t teaching what we wanted to learn. Plus, after reading the on-the-road adventures by Jack Kerouac, Charles Kuralt, and John Steinbeck, we wanted to leave behind the cramped, windowless classrooms and confront the real world with our sketchbooks.

We filled our backpacks full of art supplies and hopped on a freight train heading east out of Los Angeles. We were too broke for hotels, so we slept in graveyards and underpasses and we sketched gravestone cutters, lumberjacks, and ex-cons. To make enough money for food, we drew two-dollar portraits in bars by the light of cigarette machines.

Here’s a picture of Tom and me wearing matching gas station uniform shirts with our sketchbooks in rural Missouri.

We made it all the way to Manhattan. We sketched the city by day, and by night we slept on abandoned piers and rooftops. We had a crazy idea to write a how-to book on sketching, so we made the rounds of the publishers. There weren’t many books in print on the subject, other than the 1976 book “On the Spot Drawing” by Nick Meglin. But our heroes were older: Menzel, Guptill, Watson, and Kautzky.

We hammered out the basic plan for the book on paper placemats in a Burger King on the Upper West Side. We were never completely comfortable with the word “sketching,” because it implied something that is cursory or casual or tentative. We wanted to do art from observation that was accurate and detailed, but more importantly, vital, probing and totally committed.

We eventually got a contract from Watson-Guptill, and the book was published in 1982. It is as much about the adventure of sketching on the road as it is about technique. It’s out of print now, very expensive to buy. Before Tom died we talked about bringing it back to print again, but we just got too busy with other projects.

MTH: What effect did that adventure have on your location work?

J.G: One effect of that trip on both of us was that we developed a healthy respect for how different people look at artwork. We set up a little stand at the Missouri state raccoon-hunting championships with the goal of doing portraits of everybody’s favorite dogs. The owners were very particular about the dogs’ proportions and markings, and they weren’t going to pay us the two dollars we were asking unless we got the details right. It was a tougher critique than we ever got in art school.

MTH: As a follow up to that, you are well known for your works of fantastic art, and your vivid realizations of ancient history (I’m thinking of the National Geographic work). These seem like ideal subjects for a illustrator– depicting things that no longer (or never did) exist – but making them as real as possible. As an Urban Sketcher, naturally I wonder how much of this you credit to your background sketching? What’s the relationship between observing the world and visualizing your imagination?

J.G: Yes, the inner eye and outer eye. The two are inseparable. A few times I got to travel on research assignments for National Geographic with the art director J. Robert Teringo, who was also a fanatic for sketching and a graduate of the Famous Artist’s School.

We brought our watercolors to Israel and Jordan and Petra while researching an archaeology story about Palestine during the time of the Caesars. I brought a camera, too, but the location studies were more useful. It wasn’t hard to imagine the clock turning back to a time before photography was invented, when artists were necessary members of archaeological expeditions.

You mention fantasy work. I’m probably best known for writing and illustrating Dinotopia, the book about a world where humans and dinosaurs coexist. Dinotopia’s whole premise is that of a 19th century explorer named Arthur Denison documenting a new world with his sketchbook. The idea for Dinotopia came directly from my on-the-road sketching days with Kinkade and my field research sketching for National Geographic.

MTH: Would you say that all of your major works have some element of field study? Which happens more often - an idea for an imaginative work that requires you to make field studies, or a sketch on location that inspires a studio painting?

It goes both ways. Sketching from life definitely builds my visual vocabulary, which helps when I’m trying to conjure a fantasy world from thin air. I often dig into my sketchbooks for poses, rock formations, trees, landscape effects, or other details. That’s one of the reasons I like to draw everything. As Adolph Menzel put it: “alles Zeichnen ist nützlich, und alles zeichnen auch" (“All drawing is useful, and to draw everything as well.”)

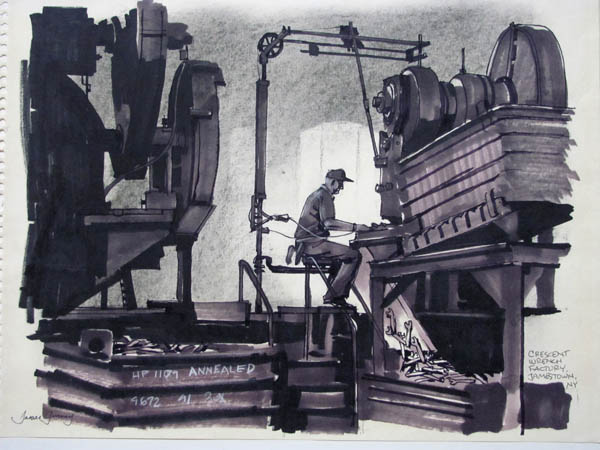

MTH: You seem to enjoy using sketching to get behind-the-scenes access. To put yourself in front of out-of-the-ordinary subjects many of us might never get to sketch. What are some of the most exotic places location sketching has taken you? When you plan these missions, how do you select a worthwhile subject? What makes your list of "must draw" places? Any advice for Urban Sketchers on how to make these adventures happen?

Rather than retell stories that I’ve told on the blog, why don’t I just mention a few experiences, and people can follow links to a fuller description.

[Crescent wrench factory]

[Dangerous neighborhoods]

[Boat in Shanghai]

[Monkeys in Gibraltar]

MTH: There's plenty more! James' blog is encyclopedic. Some places exotic, some more commonplace.

J.G.: I have no list of must-draw places. I’m usually not interested in art-workshop destinations in Tuscany or touristy places that are overrun with artists. I prefer non-motifs, the little beauties that everyone passes by. The sketches that mean the most to me are closest to my own life. I love what Andrew Wyeth did by staying within a very narrow perimeter.

MTH: In the Urban Sketching community we have a kind of ‘aesthetic agreement’ that we are all sketching from first hand observation. (At least, what we choose to post on these pages). Mostly this is because we enjoy the idea of getting out and seeing the world. But it can lead to an assumption that drawing from life is always superior to drawing from reference. We started to touch on this topic on our sketching outing, but didn’t get too far in. I get the impression you don’t use much photographic reference, or try to avoid it when possible. Is that generally true? How do you feel about all that – the from life vs. from photography question?

J.G.: I love photography and I use photographic reference in my studio work. But keep in mind that my specialty is painting realistic images of things that can’t be photographed. Photos only get you part way there. For that work, I build maquettes and get people to pose and look at reference. But what I’m actually visualizing is something that is altogether beyond the reach of a camera, such as a dinosaur, an ancient Roman, or a mech robot.

When I’m outdoors sketching from observation, my goals are very different. I’m trying to catch life on the run. I love the challenge of trying to record changing light and moving subjects.

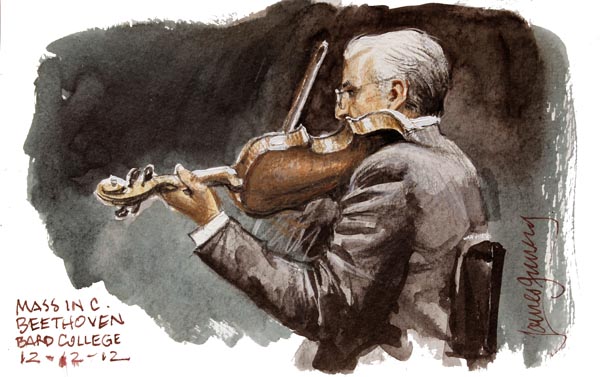

[Mass in C]

The sense of urgency that it induces in me forces me to improvise and act on intuition. There would be no reason for me to take photos on location and work from them in the studio, because that exercise would have no purpose and would hold no interest for me.

MTH: So, your YouTube channel is pretty awesome!

Your mini-documentaries of your sketching outings are quite sophisticated - voice over, multiple cameras, establishing footage, even tracking shots. And you’re very generous with the amount of content.

It must take a lot of mental energy, juggling between doing the artwork and operating multiple cameras. Can I just outright ask – what makes all of that worthwhile? You’re a rare example, an artist who chooses to do all that on location. Many of us would find it terribly distracting. Yet you are able to make excellent drawings, and be a documentary filmmaker at the same time. (Not that I am trying to get you to stop – please do keep making these films).

J.G.: Thanks. Why do I do it? I grew up in a family with no artists, I didn’t take art classes, and I was kind of a loner. So all through my youth, I never got to watch anyone else drawing or painting from life.

Once I arrived at art school and started meeting other artists, I was completely captivated with how other people made a picture. And I was fascinated to learn what they were thinking about as they did so.

I believe that drawing from observation is an intensely magical act, like a form of conjuring. What I’m trying to do with my videos is to try to bottle that magic, to catch the fish and tell the fish story at the same time.

[Sketchbook Pochade - Note Gopro Hero attached to egg timer. Some Yankee ingenuity at work.]

Yes, it takes a good deal of focused attention to document a sketch while I’m making it. Sometimes I get so wrapped up in a piece that I forget to get good coverage.

But a separate film crew can’t get the kind of coverage I’m after. They’re always on the outside looking in. In my videos, I not only want to show the viewer what I’m doing close up, but also to let them inside my head so they can see what I’m thinking.

The other answer to what makes it worthwhile is that over the next few years I will be building a library of instructional videos for sale showing in detail how I use various media and how I solve various problems.

In 2014 I will be releasing a video on watercolor painting on location, followed by other plein-air media.

MTH: Do you have some tips for a sketcher who wants to capture their own work on video? Some good introductory gear, or reliable techniques.

J.G.: Let’s start with techniques—Basic tips for shooting video of urban sketching:

1. If you’re a beginner, use a tripod and NEVER pan or zoom.

2. Get coverage. Shoot a lot of four second clips. It really helps to have a nice range of shots: an establishing shot, some closeups, some palette or pencil box shots, time lapse, reaction shots of people around you, plus a shot of the motif that you’re looking at. Get some audio background sounds and add voiceover later if you don’t want to narrate what you’re doing in real time. Editing is much easier if you’ve got good coverage, and it’s frustrating for the viewer if you don’t.

3. Get a camera with manual controls, esp: focus lock, custom white balance, and manual exposure control, and learn to use them.

4. You can use a basic editing program like iMovie. Edit your footage down as much as possible. Art in real time, like life in real time, is boring. It only gets exciting when it’s well edited.

Gear:

1. I use relatively inexpensive gear: a Canon Vixia HF R40 camcorder, a Canon T3i digital SLR, and a GoPro Hero2, with audio recorded on an H1 Zoom. I purchased all that gear for around $1,000.

2. All the dolly rigs and motion control rigs are super cheap DIY workshop projects using Legos and broomsticks and stuff like that.

3. I learned about video shooting and editing techniques from watching YouTube tutorials online. I shoot and edit all my own stuff.

MTH: Orling Dominguez of the Dominican Republic wanted me to ask about your technical process. You have an interesting mixed media approach, open to any tool or technique you can combine. What are you thinking as you bring all these different materials together? Have you developed a step-by-step process to your choices, or is it more ‘by feel’? What makes something suited for one approach over another?

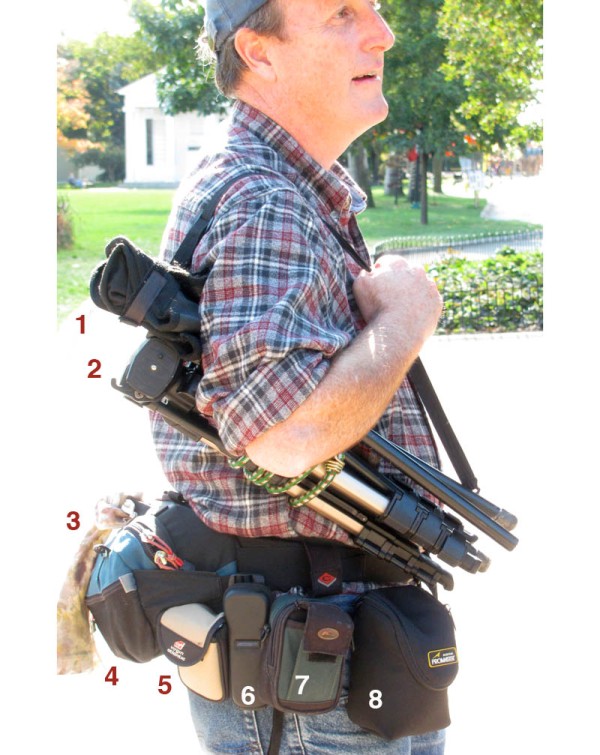

J.G.: Good question, Orling. In my urban sketching kit, I bring art supplies that are totally cross-compatible: a fountain pen, water-soluble colored pencils and graphite pencils, water brushes (one with water and a couple others with water-soluble colored inks), a small Schmincke watercolor pan set, and a few tubes of gouache. I also have an oil painting kit and a casein kit.

[What's in my bag?]

Basic thinking: there is no line between drawing and painting, and there are no “purist” rules. Anything goes as long as it’s conservationally sound. I use whatever media or methods convey the most information or mood in the time available. And of course, I only bring out what is reasonable to use in a given situation, such as a concert hall, a subway, or a restaurant.

[Plein Air Monterey]

[James's watercolor gear. Not afraid to be an art nerd I see. I kid! We are all the same.]

MTH: I’m always interested if an artist has a philosophy about this: What makes something a sketch vs. a painting? Is that line so blurry you don’t even worry about it any longer?

I don’t place any boundaries between a sketch and a finish, or between a drawing and a painting. I like the word “study” because it implies a more carefully observant and patient mindset, but a work done as a study from life can have the power and detail of a finished work as well. A study is not necessarily a means to an end. But since we have to call our works something when we refer to them, we’re stuck with the limitations of the lexicon.

MTH: You have always been an example to other artists of a self-taught, highly motivated individual who is doing their own thing. Given that, I think this is a great closing question from Nina Johansson from Stockholm:

"I assume that Gurney lives off of his art, and it would be interesting to get some hands-on advice for others who dream of doing that. We have been having this discussion at the school where I work, about how artists are usually not great at doing business, and how we would like to give our art students some classes in how to run a small business to be able to make a living - only the curriculum gets in the way. We'll see how it goes, but in the meantime I like to show them good examples. :)"

If I can just add to that: I'm assuming at this stage of your career, you can pretty much do what you want, pick your projects. What do you see as the most interesting ventures for artists in the next decade?

[Highland Avenue]

Thanks, yes, it’s true, I’ve always lived off the brush and I’ve always painted what I want. Some years a lot of money rolls in; other years I make less than a janitor. But I’ve always been happy and followed my muse.

[Mud Puddle]

I believe every art student should get schooling in business: marketing, contracts, accounting, publicity, and especially in this age of creator-producer, it’s important to know about distribution, and sales. If art schools don’t offer this, you can pick it up on your own. I’m always trying to learn new things about how to make what I love to do pay for my living.

That said, I try to keep business considerations from driving what I do or how I do it. I just want to have fun doing the very best quality work I can. I’m glad that the internet lets me share what I produce and what I learn with others. I have faith that enough people will support me to keep me doing it.

[Bleecker and 11th]

Sketching from life is making big strides forward, both with the Urban Sketchers and the plein-air-painting movements. Some people make a living doing these things, but that’s not why they’re important. People who sketch in their spare time from other jobs, and professionals who do it for relaxation or learning are just as important to the movement.

Working directly from nature has always brought fresh blood into Art, and we’re all lucky to be living in the midst of this revival.

MTH: Well, thanks for all your generous time - you've given us great answers, it's been really excellent having you! Hope to see you sketching on the street. If you're ever on the road, feel free to look up the local Urban Sketchers group wherever you are."

MTH: I asked around if any of our sketchers had a question for you. Here’s one that’s a great opener from Cathy Johnson of Missouri: "I've loved James Gurney since his very first book, back in the 80s; The Artist's Guide to Sketching, with Thomas Kinkade (yes, that Kinkade--they took different paths!) Two young men taking off to sketch across America...it's delightful! "

J.G: Thanks, Cathy! I love your work too, ever since I first saw it in An Illustrated Life.

Tom Kinkade and I were assigned together as freshmen roommates at UC Berkeley when we were both 17 years old. Over the years we went on a lot of sketching adventures together. I knew him long before he became the “Painter of Light.”

We both went to the same art school, but we left after a couple semesters because we started getting jobs, and the school wasn’t teaching what we wanted to learn. Plus, after reading the on-the-road adventures by Jack Kerouac, Charles Kuralt, and John Steinbeck, we wanted to leave behind the cramped, windowless classrooms and confront the real world with our sketchbooks.

We filled our backpacks full of art supplies and hopped on a freight train heading east out of Los Angeles. We were too broke for hotels, so we slept in graveyards and underpasses and we sketched gravestone cutters, lumberjacks, and ex-cons. To make enough money for food, we drew two-dollar portraits in bars by the light of cigarette machines.

Here’s a picture of Tom and me wearing matching gas station uniform shirts with our sketchbooks in rural Missouri.

We made it all the way to Manhattan. We sketched the city by day, and by night we slept on abandoned piers and rooftops. We had a crazy idea to write a how-to book on sketching, so we made the rounds of the publishers. There weren’t many books in print on the subject, other than the 1976 book “On the Spot Drawing” by Nick Meglin. But our heroes were older: Menzel, Guptill, Watson, and Kautzky.

We hammered out the basic plan for the book on paper placemats in a Burger King on the Upper West Side. We were never completely comfortable with the word “sketching,” because it implied something that is cursory or casual or tentative. We wanted to do art from observation that was accurate and detailed, but more importantly, vital, probing and totally committed.

We eventually got a contract from Watson-Guptill, and the book was published in 1982. It is as much about the adventure of sketching on the road as it is about technique. It’s out of print now, very expensive to buy. Before Tom died we talked about bringing it back to print again, but we just got too busy with other projects.

MTH: What effect did that adventure have on your location work?

J.G: One effect of that trip on both of us was that we developed a healthy respect for how different people look at artwork. We set up a little stand at the Missouri state raccoon-hunting championships with the goal of doing portraits of everybody’s favorite dogs. The owners were very particular about the dogs’ proportions and markings, and they weren’t going to pay us the two dollars we were asking unless we got the details right. It was a tougher critique than we ever got in art school.

MTH: As a follow up to that, you are well known for your works of fantastic art, and your vivid realizations of ancient history (I’m thinking of the National Geographic work). These seem like ideal subjects for a illustrator– depicting things that no longer (or never did) exist – but making them as real as possible. As an Urban Sketcher, naturally I wonder how much of this you credit to your background sketching? What’s the relationship between observing the world and visualizing your imagination?

J.G: Yes, the inner eye and outer eye. The two are inseparable. A few times I got to travel on research assignments for National Geographic with the art director J. Robert Teringo, who was also a fanatic for sketching and a graduate of the Famous Artist’s School.

We brought our watercolors to Israel and Jordan and Petra while researching an archaeology story about Palestine during the time of the Caesars. I brought a camera, too, but the location studies were more useful. It wasn’t hard to imagine the clock turning back to a time before photography was invented, when artists were necessary members of archaeological expeditions.

You mention fantasy work. I’m probably best known for writing and illustrating Dinotopia, the book about a world where humans and dinosaurs coexist. Dinotopia’s whole premise is that of a 19th century explorer named Arthur Denison documenting a new world with his sketchbook. The idea for Dinotopia came directly from my on-the-road sketching days with Kinkade and my field research sketching for National Geographic.

MTH: Would you say that all of your major works have some element of field study? Which happens more often - an idea for an imaginative work that requires you to make field studies, or a sketch on location that inspires a studio painting?

It goes both ways. Sketching from life definitely builds my visual vocabulary, which helps when I’m trying to conjure a fantasy world from thin air. I often dig into my sketchbooks for poses, rock formations, trees, landscape effects, or other details. That’s one of the reasons I like to draw everything. As Adolph Menzel put it: “alles Zeichnen ist nützlich, und alles zeichnen auch" (“All drawing is useful, and to draw everything as well.”)

MTH: You seem to enjoy using sketching to get behind-the-scenes access. To put yourself in front of out-of-the-ordinary subjects many of us might never get to sketch. What are some of the most exotic places location sketching has taken you? When you plan these missions, how do you select a worthwhile subject? What makes your list of "must draw" places? Any advice for Urban Sketchers on how to make these adventures happen?

Rather than retell stories that I’ve told on the blog, why don’t I just mention a few experiences, and people can follow links to a fuller description.

[Crescent wrench factory]

[Dangerous neighborhoods]

[Boat in Shanghai]

[Monkeys in Gibraltar]

MTH: There's plenty more! James' blog is encyclopedic. Some places exotic, some more commonplace.

The Metropolitan Opera | Gorillas at the Zoo | Nursing Home | Antique Dealer, Tangier | Car Dealership | Laundromat | Supermarket Loading Dock

J.G.: I have no list of must-draw places. I’m usually not interested in art-workshop destinations in Tuscany or touristy places that are overrun with artists. I prefer non-motifs, the little beauties that everyone passes by. The sketches that mean the most to me are closest to my own life. I love what Andrew Wyeth did by staying within a very narrow perimeter.

MTH: In the Urban Sketching community we have a kind of ‘aesthetic agreement’ that we are all sketching from first hand observation. (At least, what we choose to post on these pages). Mostly this is because we enjoy the idea of getting out and seeing the world. But it can lead to an assumption that drawing from life is always superior to drawing from reference. We started to touch on this topic on our sketching outing, but didn’t get too far in. I get the impression you don’t use much photographic reference, or try to avoid it when possible. Is that generally true? How do you feel about all that – the from life vs. from photography question?

J.G.: I love photography and I use photographic reference in my studio work. But keep in mind that my specialty is painting realistic images of things that can’t be photographed. Photos only get you part way there. For that work, I build maquettes and get people to pose and look at reference. But what I’m actually visualizing is something that is altogether beyond the reach of a camera, such as a dinosaur, an ancient Roman, or a mech robot.

When I’m outdoors sketching from observation, my goals are very different. I’m trying to catch life on the run. I love the challenge of trying to record changing light and moving subjects.

[Mass in C]

The sense of urgency that it induces in me forces me to improvise and act on intuition. There would be no reason for me to take photos on location and work from them in the studio, because that exercise would have no purpose and would hold no interest for me.

MTH: So, your YouTube channel is pretty awesome!

Your mini-documentaries of your sketching outings are quite sophisticated - voice over, multiple cameras, establishing footage, even tracking shots. And you’re very generous with the amount of content.

It must take a lot of mental energy, juggling between doing the artwork and operating multiple cameras. Can I just outright ask – what makes all of that worthwhile? You’re a rare example, an artist who chooses to do all that on location. Many of us would find it terribly distracting. Yet you are able to make excellent drawings, and be a documentary filmmaker at the same time. (Not that I am trying to get you to stop – please do keep making these films).

J.G.: Thanks. Why do I do it? I grew up in a family with no artists, I didn’t take art classes, and I was kind of a loner. So all through my youth, I never got to watch anyone else drawing or painting from life.

Once I arrived at art school and started meeting other artists, I was completely captivated with how other people made a picture. And I was fascinated to learn what they were thinking about as they did so.

I believe that drawing from observation is an intensely magical act, like a form of conjuring. What I’m trying to do with my videos is to try to bottle that magic, to catch the fish and tell the fish story at the same time.

[Sketchbook Pochade - Note Gopro Hero attached to egg timer. Some Yankee ingenuity at work.]

Yes, it takes a good deal of focused attention to document a sketch while I’m making it. Sometimes I get so wrapped up in a piece that I forget to get good coverage.

But a separate film crew can’t get the kind of coverage I’m after. They’re always on the outside looking in. In my videos, I not only want to show the viewer what I’m doing close up, but also to let them inside my head so they can see what I’m thinking.

The other answer to what makes it worthwhile is that over the next few years I will be building a library of instructional videos for sale showing in detail how I use various media and how I solve various problems.

In 2014 I will be releasing a video on watercolor painting on location, followed by other plein-air media.

MTH: Do you have some tips for a sketcher who wants to capture their own work on video? Some good introductory gear, or reliable techniques.

J.G.: Let’s start with techniques—Basic tips for shooting video of urban sketching:

1. If you’re a beginner, use a tripod and NEVER pan or zoom.

2. Get coverage. Shoot a lot of four second clips. It really helps to have a nice range of shots: an establishing shot, some closeups, some palette or pencil box shots, time lapse, reaction shots of people around you, plus a shot of the motif that you’re looking at. Get some audio background sounds and add voiceover later if you don’t want to narrate what you’re doing in real time. Editing is much easier if you’ve got good coverage, and it’s frustrating for the viewer if you don’t.

3. Get a camera with manual controls, esp: focus lock, custom white balance, and manual exposure control, and learn to use them.

4. You can use a basic editing program like iMovie. Edit your footage down as much as possible. Art in real time, like life in real time, is boring. It only gets exciting when it’s well edited.

Gear:

1. I use relatively inexpensive gear: a Canon Vixia HF R40 camcorder, a Canon T3i digital SLR, and a GoPro Hero2, with audio recorded on an H1 Zoom. I purchased all that gear for around $1,000.

2. All the dolly rigs and motion control rigs are super cheap DIY workshop projects using Legos and broomsticks and stuff like that.

3. I learned about video shooting and editing techniques from watching YouTube tutorials online. I shoot and edit all my own stuff.

MTH: Orling Dominguez of the Dominican Republic wanted me to ask about your technical process. You have an interesting mixed media approach, open to any tool or technique you can combine. What are you thinking as you bring all these different materials together? Have you developed a step-by-step process to your choices, or is it more ‘by feel’? What makes something suited for one approach over another?

J.G.: Good question, Orling. In my urban sketching kit, I bring art supplies that are totally cross-compatible: a fountain pen, water-soluble colored pencils and graphite pencils, water brushes (one with water and a couple others with water-soluble colored inks), a small Schmincke watercolor pan set, and a few tubes of gouache. I also have an oil painting kit and a casein kit.

[What's in my bag?]

Basic thinking: there is no line between drawing and painting, and there are no “purist” rules. Anything goes as long as it’s conservationally sound. I use whatever media or methods convey the most information or mood in the time available. And of course, I only bring out what is reasonable to use in a given situation, such as a concert hall, a subway, or a restaurant.

[Plein Air Monterey]

[James's watercolor gear. Not afraid to be an art nerd I see. I kid! We are all the same.]

MTH: I’m always interested if an artist has a philosophy about this: What makes something a sketch vs. a painting? Is that line so blurry you don’t even worry about it any longer?

I don’t place any boundaries between a sketch and a finish, or between a drawing and a painting. I like the word “study” because it implies a more carefully observant and patient mindset, but a work done as a study from life can have the power and detail of a finished work as well. A study is not necessarily a means to an end. But since we have to call our works something when we refer to them, we’re stuck with the limitations of the lexicon.

MTH: You have always been an example to other artists of a self-taught, highly motivated individual who is doing their own thing. Given that, I think this is a great closing question from Nina Johansson from Stockholm:

"I assume that Gurney lives off of his art, and it would be interesting to get some hands-on advice for others who dream of doing that. We have been having this discussion at the school where I work, about how artists are usually not great at doing business, and how we would like to give our art students some classes in how to run a small business to be able to make a living - only the curriculum gets in the way. We'll see how it goes, but in the meantime I like to show them good examples. :)"

If I can just add to that: I'm assuming at this stage of your career, you can pretty much do what you want, pick your projects. What do you see as the most interesting ventures for artists in the next decade?

[Highland Avenue]

Thanks, yes, it’s true, I’ve always lived off the brush and I’ve always painted what I want. Some years a lot of money rolls in; other years I make less than a janitor. But I’ve always been happy and followed my muse.

[Mud Puddle]

I believe every art student should get schooling in business: marketing, contracts, accounting, publicity, and especially in this age of creator-producer, it’s important to know about distribution, and sales. If art schools don’t offer this, you can pick it up on your own. I’m always trying to learn new things about how to make what I love to do pay for my living.

That said, I try to keep business considerations from driving what I do or how I do it. I just want to have fun doing the very best quality work I can. I’m glad that the internet lets me share what I produce and what I learn with others. I have faith that enough people will support me to keep me doing it.

[Bleecker and 11th]

Sketching from life is making big strides forward, both with the Urban Sketchers and the plein-air-painting movements. Some people make a living doing these things, but that’s not why they’re important. People who sketch in their spare time from other jobs, and professionals who do it for relaxation or learning are just as important to the movement.

Working directly from nature has always brought fresh blood into Art, and we’re all lucky to be living in the midst of this revival.

MTH: Well, thanks for all your generous time - you've given us great answers, it's been really excellent having you! Hope to see you sketching on the street. If you're ever on the road, feel free to look up the local Urban Sketchers group wherever you are."

Thank you, Marc! Those were thought-provoking questions. All the best to my fellow Urban Sketchers everywhere.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)