(Note: This is the third and final part of a series of posts adapted from Imaginative Realism, Andrews McMeel, October, 2009). Please follow these links to the earlier posts, Part 1 and Part 2.)

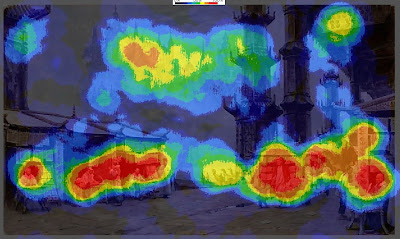

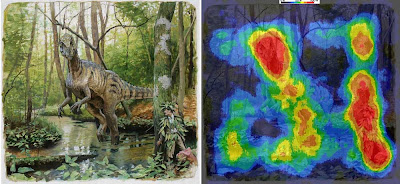

By adding together the eye movement data from a group of test subjects, we can learn where most people look in a given picture.

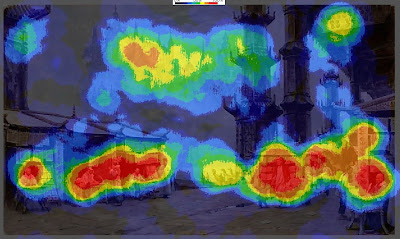

To create the image below, the eye-tracking technology recorded the scanpath data of sixteen different subjects and compiled the information into composite images, called heatmaps. The red and orange colors show where 80-100% of the subjects halted their gaze. The bluer or darker areas show where hardly anyone looked.

Here’s the heatmap for the painting Marketplace of Ideas, which we discussed in the last two posts.

It turns out that there was very little interest in either of the main vertical columns. Instead, the red splotches reveal a concentration of interest in the figures. There were secondary interest areas in the far buildings and the sign in the upper right.

The interest in people, especially faces, appears to reflect a hardwired instinct to understand our fellow humans.

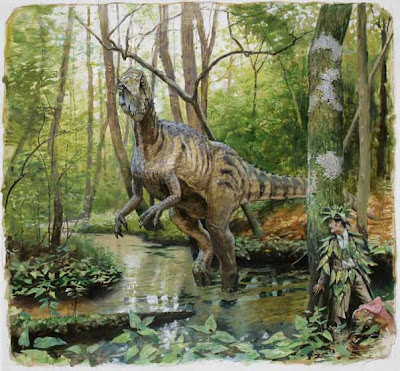

In the heatmap for

Chasing Shadows, which shows a group of children running along a beach with a Brachiosaurus, there’s a strong focal point around the dinosaur's front feet and the nearby running children.

There are secondary points of interest at the dinosaur’s head and the leading child. Note how the action of the walking pose was read without directly looking at the rear leg.

Other spots of interest congregate around the dinosaur’s tail, the base and the top of the tree, and the vanishing point along the beach.

Hardly anyone looked directly at the sky, the upper palm fronds, or the middle section of the palm trunk. But these areas were presumably perceived in the halo of peripheral vision around the center point of vision.

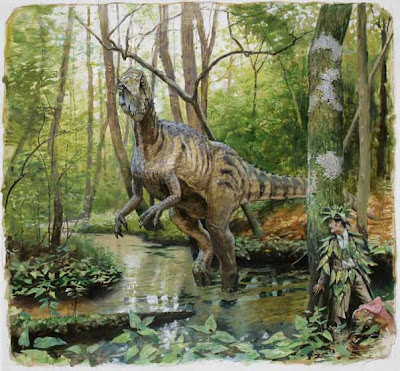

Have a look at this painting, and be aware of where your eyes travel.

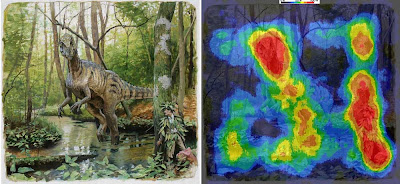

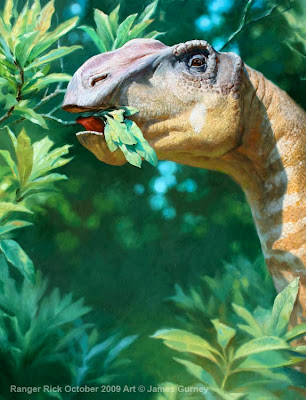

The heatmap for the painting

Camouflage (click to enlarge) shows that everyone noticed the dinosaur’s face. They also spotted the hidden man and the small pink dinosaur.

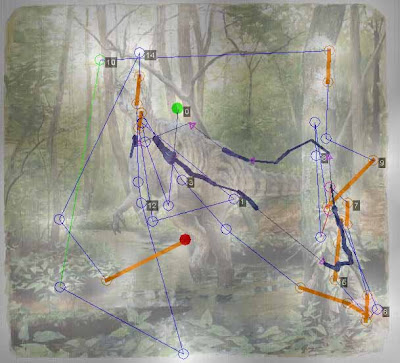

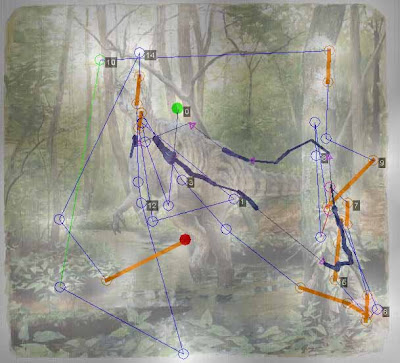

According to statistical data connected to timing, these three faces drew almost everyone’s attention within the first five seconds. The dinosaur's face was statistically the first thing most people looked at, followed quickly by the hiding man. Below is one subject's scanpath, with the black numbers counting off seconds.

I was surprised that the two patches of lichen on the tree above the man scored near 100% attention. Evidently viewers noticed these strange shapes in their peripheral vision and checked them to make sure they weren’t important, or somehow a threat to the man. From a narrative standpoint, I suppose they were a bit of a red herring, distracting with no payoff.

The sunken log and the detailed patch of leaves in the lower left drew 60% of the viewers, perhaps because those were likely places for other dangers to hide.

Just because an element has sharp detail or strong tonal contrasts, it doesn’t necessarily attract the eye. The dark branches behind the dinosaur’s head drew almost no attention because they fit into the natural schema of a forest scene. Apparently the viewers developed a search strategy based on the threatening situation of a hungry dinosaur looking for a bite to eat.

PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS

These experiments force us to question a few of our cherished notions about composition and picture-gazing.

1. The eye does not flow in smooth curves or circles, nor does it follow contours. It leaps from one point of interest to another. Curving lines or other devices may be "felt" in some way peripherally, but the eye doesn't move along them.

2. Placing an element on a golden section grid line doesn’t automatically attract attention. If an attention-getting element such as a face is placed in the scene, it will gather attention wherever you place it.

3. Two people don’t scan the same picture along the same route. But they do behave according to an overall strategy that alternates between establishing context and studying detail.

4. The viewer is not a passive player continuously controlled by a composition. Each person confronts an image actively, driven by a combination of conscious and unconscious impulses, which are influenced, but not determined, by the design of the picture.

5. The unconscious impulses seem to include the establishment of hierarchies of interest based on normal expectations or schema of a scene. For example, highly contrasting patterns of foliage or branches will not directly draw the gaze unless they are perceived as anomalous in the peripheral vision.

5. As pictorial designers we shouldn’t think in abstract terms alone. Abstract design elements do play a role in influencing where viewers look in a picture, but in pictures that include people or animals or a suggestion of a story, the human and narrative elements are what direct our exploration of a picture.

As Dr. Edwards succinctly puts it, “abstract design gets trumped by human stories.” The job of the artist, then, in composing pictures about people is to use abstract tools to reinforce the viewer’s natural desire to seek out a face and a story.

--------------

Related posts on GurneyJourney:

Eyetracking and Composition, part 1

Eyetracking and Composition, part 2

Eyetracking and Composition part 3

Introduction to eyetracking,

link.

How perception of faces is coded differently,

link.

All the paintings are from

Dinotopia: Journey to Chandara.

Many thanks to the team at

Eyetools, Inc. for their assistance.

The exhibition includes that hard-to-classify artzone known as lowbrow, pop surrealism, graffiti, tattoo culture, and contemporary fantasy art. My recent painting called "Birdman" will be included in the show. More on the making of Birdman in a future post.

The exhibition includes that hard-to-classify artzone known as lowbrow, pop surrealism, graffiti, tattoo culture, and contemporary fantasy art. My recent painting called "Birdman" will be included in the show. More on the making of Birdman in a future post. It's been a tough workout, but I think I'm finally in shape and ready to rock!

It's been a tough workout, but I think I'm finally in shape and ready to rock!