Sunday, May 31, 2015

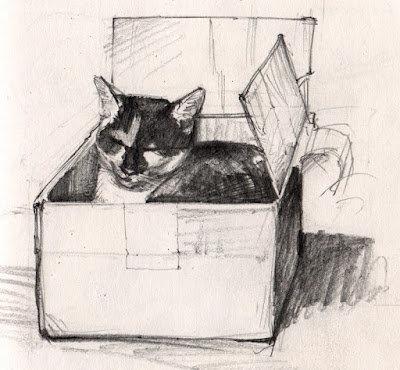

Cat in a Box

Here's a pencil sketch from more than 10 years ago, when we had a kitten named Sunlight, and she always loved to curl up in an empty box.

Labels:

Animals,

Pencil Sketching

Saturday, May 30, 2015

From Yellow Blob to Barnyard

|

| Barnyard Light, gouache, 5 x 8 inches. |

After a basic drawing in watercolor pencils, I added thin layers of gouache with a flat brush. The casein underpainting is a closed surface, meaning it won't dissolve again once it's dry.

The barnyard was actually lit rather evenly. To carry off the selective light effect, I darkened and cooled the tones in all the surrounding areas, and kept the lit areas pale and warm.

-----

Good news on the upcoming tutorial video "Gouache in the Wild." I locked the edit earlier this week, and am now designing the cover. One of the six painting adventures is an example like this, where I show how to create a theatrical light effect on location.

Friday, May 29, 2015

GJ Book Club: Speed on Mass Drawing

On the GJ Book Club, we're studying Chapter 9: Mass Drawing: Practical," from Harold Speed's 1917 classic The Practice and Science of Drawing.

The following numbered paragraphs cite key points in italics, followed by a brief remark of my own. If you would like to respond to a specific point, please precede your comment by the corresponding number. There's a lot of content here, so let's dive in!

1. Painting is drawing.

In this chapter, Harold Speed demonstrates his conception of monochrome painting as a form of drawing. He calls it "mass drawing," and unlike line drawing, there's a greater attention to shape, value, and edges.

2. Most objects can be reduced broadly into three tone masses, the lights (including the high lights, the half tones, and the shadows.

Speed's demonstration follows a process where he maps out the shapes in charcoal (sealed with shellac), then scrubs a thin layer of tone overall equal to the halftone.

Then the lights are painted into the wet halftone later. "Gradations are got by thinner paint, which is mixed with the wet middle tone of the ground."

Note: This is not a 'line drawing' but rather a map of masses.

9. Importance of anatomy and cautions about overstating it.

Speed ends with a discussion of the importance of anatomical knowledge, but cautions against "overstepping the modesty of nature." He says, "Never let anatomical knowledge tempt you into exaggerated statements of internal structure, unless such exaggeration helps the particular thing you wish to express." When I worked with Frank Frazetta on Fire and Ice, he was always making this point, complaining about figure work that was overly musclebound.

10. Painting across vs. along the form.

Here he continues the point made in the previous chapter, but specifically talking about the brush.

11. Keep the lights separate from the shadows, let the half tone paper always come as a buffer state between them.

This is an essential point, extremely important in outdoor work under the full sun. In figure work indoors, mass drawing can also be done with red and white chalk on a tone paper where the paper equals the halftone value of the form.

The following numbered paragraphs cite key points in italics, followed by a brief remark of my own. If you would like to respond to a specific point, please precede your comment by the corresponding number. There's a lot of content here, so let's dive in!

1. Painting is drawing.

In this chapter, Harold Speed demonstrates his conception of monochrome painting as a form of drawing. He calls it "mass drawing," and unlike line drawing, there's a greater attention to shape, value, and edges.

2. Most objects can be reduced broadly into three tone masses, the lights (including the high lights, the half tones, and the shadows.

Speed's demonstration follows a process where he maps out the shapes in charcoal (sealed with shellac), then scrubs a thin layer of tone overall equal to the halftone.

|

| a. Blocking out shapes, b. middle tone 'scrumbled' over the whole |

|

| c. Addition of the darks, d. finished work |

Note the swatches of paint used at lower left. He's using raw umber and white. "Don't use much medium," he advises. This method is also discussed by Norman Rockwell in "Norman Rockwell Illustrator," where he calls it "painting into the soup."

3. The use of charcoal to the neglect of line drawing often gets the student into a sloppy manner of work, and is not so good a training to the eye and hand in a clear, definite statement.

I found this statement interesting. He seems to be suggesting that the monochrome painting leads to better results in students than the classic tonal charcoal study. But he admits that this particular method of painting into the halftone value isn't always useful for full-color painting because it can pollute the shadows. He'll get into color painting in later chapters (and in his next book), but basically he advises mixing up separate middle tone values for lights and shadows.

4. Try always to do as much as possible with one stroke of the brush.

This important statement leads off a discussion of the variable strokes and edges provided by various kinds of brushes. The brush adds the ability to place a definite shape, but also to feather the edges on the sides of the stroke. In addition, because of the amount of paint on the brush, it can leave a lighter (or darker) stroke relative to the value of the wet halftone layer.

5. Brush shapes.

Speed's chart shows rounds, flats, and filberts at the bottom, but the one in the third row he calls "Class C" seems to be a flat with rounded corners. Does anyone know whether that type of brush is still being made these days? From left to right are definite thick-paint strokes to feathery thin strokes.

6. How to fix errors, how to check accuracy.

He advises something like sight-size, namely setting the work next to the subject and comparing. He also suggests a "black glass," which is a "Lorraine mirror" mentioned in an earlier post of GurneyJourney. He discusses why the setting-out drawing must be accurately measured, but also urges students to be willing to "lose the drawing" under the paint. "It is often necessary when a painting is nearly right to destroy the whole thing in order to accomplish the apparently little that still divides it from what you conceive it to be."

7. Nothing is so characteristic of bad modelling as "gross roundness."

"The surface of a sphere is the surface with the least character," he says. This is an extension of the earlier discussion about the aesthetic importance of retaining some straight lines and planes, the sense of the partially carved block.

8. Study from Life:

|

| Blocking out the spaces occupied by masses. |

|

| Middle tone applied overall and lights placed. |

|

| Shadows added. |

|

| Completed head. |

Speed ends with a discussion of the importance of anatomical knowledge, but cautions against "overstepping the modesty of nature." He says, "Never let anatomical knowledge tempt you into exaggerated statements of internal structure, unless such exaggeration helps the particular thing you wish to express." When I worked with Frank Frazetta on Fire and Ice, he was always making this point, complaining about figure work that was overly musclebound.

10. Painting across vs. along the form.

Here he continues the point made in the previous chapter, but specifically talking about the brush.

11. Keep the lights separate from the shadows, let the half tone paper always come as a buffer state between them.

This is an essential point, extremely important in outdoor work under the full sun. In figure work indoors, mass drawing can also be done with red and white chalk on a tone paper where the paper equals the halftone value of the form.

---

The Practice and Science of Drawing is available in various formats:

1. Inexpensive softcover edition from Dover, (by far the majority of you are reading it in this format)

3. Free online Archive.org edition.

Articles on Harold Speed in the Studio Magazine The Studio, Volume 15, "The Work of Harold Speed" by A. L. Baldry. (XV. No. 69. — December, 1898.) page 151.

and The Windsor Magazine, Volume 25, "The Art of Mr. Harold Speed" by Austin Chester, page 335. (thanks, अर्जुन)

Thursday, May 28, 2015

Fidelia Bridges

|

| Fidelity Bridges, Milkweeds, 1876. Watercolor and gouache on paper |

Fidelia Bridges (1834 - 1923) was known for her meticulous botanical studies, many of which were painted outdoors in nature.

Both of her parents died when she was in her teens. She never married, but had a small circle of friends, including Mark Twain, for whom she served for a time as a governess of his daughters.

She lived by herself in a home in Canaan, Connecticut, overlooking a stream and a flower garden filled with birds and butterflies. A writer of the time described her this way:

"She soon became a familiar village figure, tall, elegant, beautiful even in her sixties, her hair swept back, her attire always formal, even when sketching in the fields or riding her bicycle through town. Her life was quiet and un-ostentatious, her friends unmarried ladies of refinement and of literary and artistic task who she joined for woodland picnics and afternoon teas."

"She soon became a familiar village figure, tall, elegant, beautiful even in her sixties, her hair swept back, her attire always formal, even when sketching in the fields or riding her bicycle through town. Her life was quiet and un-ostentatious, her friends unmarried ladies of refinement and of literary and artistic task who she joined for woodland picnics and afternoon teas."

|

| Fidelia Bridges, Calla Lily, 1875 |

She was inspired by reading John Ruskin's Modern Painters, which preached truth to nature. She found her way to study under William Trost Richards, who became a lifelong mentor. Her early studies in watercolor and gouache, such as this one of a calla lily, show a patient and observant eye.

Bridges was one of only seven women who became members of the American Watercolor Society in the 19th century. She worked for the Prang company in her later career, and her work was often reproduced on greeting cards.

-----

Labels:

Academic Painters,

Plein Air Painting

Wednesday, May 27, 2015

Dan Gurney's Sons Drive His Cars at Indy

My cousin Dan Gurney was mighty proud last Sunday when his four sons took some laps around the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in four of his creations. (link to YouTube)

Plein-Air Painting in the 1920s

A silent black-and-white film from the 1920s (Link to YouTube) turned up in the basement of an art club.

At 2:03, it shows a group of well dressed men painting outdoors, using a variety of easels that were typical of the time.

-----

Thanks, Stuart Fullerton and Robert Horvath.

Tuesday, May 26, 2015

W.T. Richards "Into the Woods"

William Trost Richards painted Into the Woods when he was about 27 years old. It's in oil, and it's not large (15.5 x 20 inches / 39.7 x 51 cm).

|

| William Trost Richards, Into the Woods, oil/canvas, 1860 |

I would guess that it was painted entirely on the spot in at least a dozen sittings, and probably in at least two different locations. As with some of Asher B. Durand's woodland studies, the foreground and background seem to be composited together. Such complete vistas rarely exist readymade in nature.

|

| William Trost Richards, Woodland Brook, 1861 |

Several artists tried to take up the idea, but WTR did so with the most tenacity. One observer said "he persisted, and carried imitation in art further" than the other pioneers. Another commentator noted that he had "a slow, keen vision, and a slow, sure hand."

Other critics argued that he missed the poetry for the details. In fact, WTR shifted his attention more to express the moods of light and atmosphere in his later canvases. Ruskin suggested that young artists begin by modeling themselves after the Pre-Raphaelites, and with that under their belts, try to emulate the more evocative aspects of Turner.

Exhibition catalog: The New Path: Ruskin and the American Pre-Raphaelites

Labels:

Hudson River School,

Plein Air Painting

Monday, May 25, 2015

Gérôme on Truth, Illustration, and Photography

Late in his life, academic painter and teacher Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) wrote a statement of his beliefs about art.

"The fact is that truth is the one thing truly good and beautiful; and, to render it effectively, the surest means are those of mathematical accuracy. Nature alone is audacious above anything human; she alone is original and picturesque. It is, then, to her that we must become attached if we wish to interest and enthuse the spectator."

|

| Illustration by Howard Pyle |

|

| Jean-Léon Gérôme - Diogenes, 1860, Walters Art Gallery |

-----

"True Gods and False in Art," by Jean-Léon Gérôme, Harpers Magazine, 1903, Vol. CVI.-No 633.— 47

Exhibition catalog: Jean-Leon Gerome

Drawing Course: Charles Bargue and Jean-Léon Gérôme

"True Gods and False in Art," by Jean-Léon Gérôme, Harpers Magazine, 1903, Vol. CVI.-No 633.— 47

Exhibition catalog: Jean-Leon Gerome

Drawing Course: Charles Bargue and Jean-Léon Gérôme

"Color and Light" in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean

We just received copies of the new Chinese hardback edition of "Color and Light: A Guide for the Realist Painter" (upper left) from the Eurasian Publishing Group / Solutions Publishing (link to publisher's web page).

There's also a Chinese softcover edition and a Japanese and Korean edition.

The little dinosaur on the cover is Mei long, from China's Liaoning province.

Labels:

Color and Light Book

Sunday, May 24, 2015

Color Photography from 1913

In its informal pose and rich color, this photograph looks like it was shot in 1973, but actually it was taken in 1913.

It used the Autochrome process, developed in 1903 by the Lumière brothers, using glass plates covered with potato starch. Motoring pioneer Mervyn O’Gorman took the photo, with his daughter Christina posing. The lack of era-specific costume details adds to the sense of timelessness.

-----

This and seven other photos of Christina at Bored Panda.

Saturday, May 23, 2015

Exhibit Review: Benjamin-Constant in Montreal

"Marvels and Mirages" is more than an exhibition about Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant (1845-1902), and it's more than a show about Orientalism. It's a loving embrace of the broader themes of exoticism and storytelling and an ambitious revival of a lost world of picture-making.

|

| Benjamin-Constant Self Portrait, gouache |

The exhibit at the Montreal Museum of Art, curated by museum director Nathalie Bondil, is the first major retrospective of Benjamin-Constant in recent times. It borrows from over 60 private and public lenders, including many regional museums in France. Several paintings were restored and reframed for the show.

|

| Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, The Pink Flamingo, 1876 |

The exhibit designers made an effort to evoke the mystery of the Near East. As you ascend the stairs into the show, Moroccan music plays softly and light filters down, influenced by shadows cast by latticework-patterned gobos.

Several glass cases show drawings, engravings, and prints. The show is divided into various themes: The Studio, the Salon, the Alhambra, Tangier, and Colonial Diplomacy. It takes some time to absorb all the captions, because there's so much exposition: political events, timelines, historical contexts, and biographical details. Woven throughout the writing are some great lines, such as "between a mirage of seduction and the veiled realities of a colonial republic."

Unfortunately—and this has nothing to do with the curation of the exhibit—there are reasons why Benjamin-Constant is not an "artist's artist." He doesn't have the psychological penetration of Repin; nor the sensitivity to color of Gerome; nor the archaeological conviction of Alma Tadema; nor the brush fluency of Sargent; nor the exquisite surfaces of Vibert or Meissonier. Some of Benjamin-Constant's paintings are frankly out of perspective, a fault that is usually hard to find among academic painters. He'll often spend a great deal of effort with background patterns without really working out the faces or the human story. Some of the paintings are huge, which magnifies their problems even more.

Unlike many other academic and Juste-Milieu painters of his time, Benjamin-Constant failed to embrace the innovations of plein-air painting. He called Impressionists "daubers" and their work "the oculist's art." That's too bad, because he would have benefited by incorporating the lessons learned from thoughtful plein-air study. For example, in the painting above, Benjamin-Constant uses a blackish dark for the farthest arch, when it really should be lifted up in value because of the intervening illuminated atmosphere.

Fortunately the show includes some of Benjamin-Constant's contemporaries. One of the standouts is the watercolor portrait by Josep Tapiro y Baro, whom I have spotlighted in a previous post.

There's also a rare chance to see some history paintings by Jean Paul Laurens. In "The Late Empire: Honorius," he shows the young emperor outmatched by his position. It's a magnificent example of subtle storytelling.

There were also several Henry Regnaults, including this watercolor (detail), which is a riot of cool reds and blue-greens over solid figure drawing. The show includes some fine examples by Gerome, Fortuny, Jose Villegas y Cordero.

But I wish the curator had included some other notable Orientalists, such as Rudolph Ernst, Frederick Bridgman, Gustave Bauernfeind, Vasily Vereshchagin, Hermann Corrodi, Leopold Carl Muller, William Logsdail, Frederick Leighton, Edwin Lord Weeks, and Ludwig Deutsch. Even though they weren't French Orientalists, their work would have raised the overall quality level of the artwork in the show.

In all, though, the museum is to be commended for rediscovering an artist who has been largely overlooked, and putting his work in context. I hope they will give a similar treatment to other neglected French artists, especially Jules Bastien-Lepage. Like the Waterhouse exhibit from a few years ago, this one provides quite a stimulus for artists. If you want to see it, it's only up until the end of the month.

There is a bilingual catalog available: Benjamin-Constant: Marvels and Mirages of Orientalism

There's a folder of high-res files of selected images.

My favorite book on Orientalism is Orientalists: Western Artists in Arabia, the Sahara, and Persia

There's a folder of high-res files of selected images.

My favorite book on Orientalism is Orientalists: Western Artists in Arabia, the Sahara, and Persia

Friday, May 22, 2015

GJ Book Club, Chapter 8—Line Drawing: Practical

On the GJ Book Club, we're studying Chapter 8, "Line Drawing: Practical," from Harold Speed's 1917 classic The Practice and Science of Drawing.

The following numbered paragraphs cite key points in italics, followed by a brief remark of my own. If you would like to respond to a specific point, please precede your comment by the corresponding number.

This is one of the core chapters of the book, with many good illustrations. Rather than try to comprehensively summarize the content, I'll just call out a few key points to provide a memory jogger and a discussion starter.

1. Appearances must be reduced to terms of a flat surface.

In many modern academic ateliers, one proceeds from a 2D shape analysis in an early stage, to a 3D construction stage later. Seeing the forms in front of you as flat shapes can be a challenge, and Speed offers various methods for doing so, including......

5. Three principles of construction.

13. Lines of shading drawn across the forms suggest softness, lines drawn in curves fullness of form, lines drawn down the forms hardness, and lines crossing in all directions so that only a mystery of tone results, atmosphere.

14. In the method of line drawing we are trying to explain (the method employed for most of the drawings by the author in this book) the lines of shading are made parallel in a direction that comes easy to the hand, unless some quality in the form suggests their following other directions.

The following numbered paragraphs cite key points in italics, followed by a brief remark of my own. If you would like to respond to a specific point, please precede your comment by the corresponding number.

This is one of the core chapters of the book, with many good illustrations. Rather than try to comprehensively summarize the content, I'll just call out a few key points to provide a memory jogger and a discussion starter.

1. Appearances must be reduced to terms of a flat surface.

In many modern academic ateliers, one proceeds from a 2D shape analysis in an early stage, to a 3D construction stage later. Seeing the forms in front of you as flat shapes can be a challenge, and Speed offers various methods for doing so, including......

2. Method for creating a drawing grid: cardboard with cutout hole, and black thread held in with sealing wax.

Over the years I have experimented with various forms of this grid, including one with black threads woven across. By the way, sealing wax is a sticky wax people would melt and then stamp with a tool for sealing letters. You could use hot glue for the same purpose.

I've found a more useful grid is a set of lines drawn with an indelible marker on a piece of acrylic or plexiglass sheet. In order to get accurate measurements, the observer must maintain a constant distance and position relative to the grid. Holding it at arm's length is one way, but there are others. Maybe in a future post or video I'll show some other methods.

3. The drawing grid or frame should be held between the eye and the object to be drawn in a perfectly vertical position.

This needs a bit of clarification. Rather than being held in a "perfectly vertical position," the grid or viewfinder should be held perpendicular to the line of sight, which is a different thing in the case of an upshot or downshot. Holding the grid vertically in such an up or down angled view would negate the normal convergent effect of vertical lines. In fact, in photography, "tilt-shift" lenses are sometimes used to artificially hold the lens vertically to negate the normal perspective of verticals.

4. It is never advisable to compare other than vertical and horizontal measurements.

A corollary to this is the importance of being able to judge a true vertical, often aided by a plumb line.

5. Three principles of construction.

A. Block out shape by analyzing into straight lines (Figure X, above)

B. Breaking down the shapes of curves. (Figure Y).

C. Vertical and side measurements. (Figure Z).

These three basic geometric methods, used in conjunction with each other, are used in the demo of the figure block-in below.

6. Method for blocking in a figure, with the prime vertical drawn through the armpit.

He also says, "Train yourself to draw between limits decided upon at the start." This is so important for placing figures accurately in multi-figure work. Some other methods, such as building outward from the center, will not serve as well for producing figures that must fit within strict limits.

7. In the case of foreshortenings, the eye, unaided by this blocking out, is always apt to be led astray.

This is so true, and in the case of foreshortenened lengths that I try to always remember to make measurements.

8. In blocking-in, observe the shape of the background as much as the object.

In many modern books, this advice is put in terms of judging "negative shapes."

9. Lines bounding one side of a form must be observed in relation to the lines bounding the other.

He continues, "The drawing of the two sides should be carried on simultaneously so that one may constantly compare them."

10. In line drawing, shading should only be used to aid the expression of form.

Even though this drawing has some tone, Speed uses it to show the way parallel lines can express form and textures like hair.

11. Diagram of a cone (seen from above) next to a window at left.

Speed proceeds to go into some detail about the theory of what we would regard highlights, terminators, core shadows, and cast shadows. But he's not primarily concerned with accurately producing a tonal analysis of form. That will come later in "mass drawing." He is still thinking in terms of a drawing conceived primarily in linear terms. That's why he suggests using the soft frontal lighting of an open window at the observer's back.

12. You seldom see any shadows in Holbein's drawings; he seems to have put his sitters near a wide window, close against which he worked.

13. Lines of shading drawn across the forms suggest softness, lines drawn in curves fullness of form, lines drawn down the forms hardness, and lines crossing in all directions so that only a mystery of tone results, atmosphere.

In his book Creative Illustration, Andrew Loomis recapitulates these same points, not only for drawing, but also painting techniques.

14. In the method of line drawing we are trying to explain (the method employed for most of the drawings by the author in this book) the lines of shading are made parallel in a direction that comes easy to the hand, unless some quality in the form suggests their following other directions.

15. Don't burden a line drawing with heavy half tones and shadows; keep them light.

He says, "The beauty that is the particular province of line drawing is the beauty of contours, and this is marred by heavy light and shade."

16. Analysis of forms of the eye, the eyebrow, and the eyelashes.

There are many good pieces of advice in the text.

---

Overview of the blog series

There are many good pieces of advice in the text.

---

The Practice and Science of Drawing is available in various formats:

1. Inexpensive softcover edition from Dover, (by far the majority of you are reading it in this format)

3. Free online Archive.org edition.

Articles on Harold Speed in the Studio Magazine The Studio, Volume 15, "The Work of Harold Speed" by A. L. Baldry. (XV. No. 69. — December, 1898.) page 151.

and The Windsor Magazine, Volume 25, "The Art of Mr. Harold Speed" by Austin Chester, page 335. (thanks, अर्जुन)

------

GJ Book Club Facebook page (Thanks, Keita Hopkinson)

Pinterest (Thanks, Carolyn Kasper)

Overview of the blog series

Thursday, May 21, 2015

Urban Sketchers, Montreal

Yesterday we painted in Montreal's Chinatown with the Urban Sketchers group.

We met at Place Sun-Yat-Sen, facing the East Gate. I used gouache, dramatizing the lighting a little to spotlight just part of the face of the main building.

There were four of us painting next to each in one small cluster, and it was fun swapping sketching stories with each other and chatting with the people who were passing by.

The photo is by Urban Sketcher correspondent Shari Blaukopf. Have a look at her painting on her daily sketchblog.

Afterward, we had a congenial supper together. Clockwise from left: Blue, Elise, Marc Holmes, his wife Laurel, Shari Blaukopf, Jeanette, Ubisoft art director Raphael Lacoste, and Chantal.

After the meal, I drew this little portrait of Raphael Lacoste.

Since we were all sketching at the table, we attracted the attention of a couple of very observant girls at the table next to us, so I invited them over to try out some water-soluble colored pencils and to watch a little demo on how to make something look 3D.

P.S. Yes, we saw the Benjamin-Constant exhibition! I'll post about it on Saturday.

-----

Urban Sketchers Montreal will meet this Sunday. Anyone is welcome to join them, and here's information about their meet-up.

Shari Blaukopf's sketch blog

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)