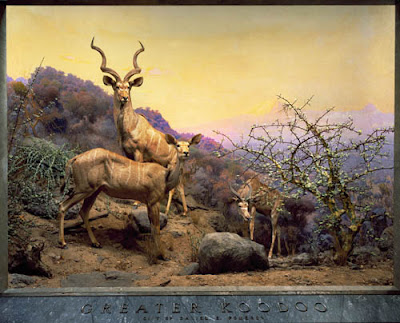

To really succeed, you have to paint a scene without any individual style. Some people call it “painting actuality.” It’s carefully composed, but composed to be artless, that is, it doesn’t make you conscious of the means it took to produce it. (Above, bighorn sheep diorama in New York, with background by

Carl Akeley, who helped develop the art of the diorama to its highest level at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, put it this way:

"The landscape painter who has cultivated a style or manner is not any good…the painted background must display a complete unity with the mounted animals. The painter must make the beholder forget that he is looking at paint, and feel that he is looking at nature itself. The artist must forget himself in his work. We must set the standard to which others will have to rise."

William R. Leigh, one of the backdrop painters for the AMNH said painting backdrops "calls for the utmost measure of truth; there is in it no place for individuality."

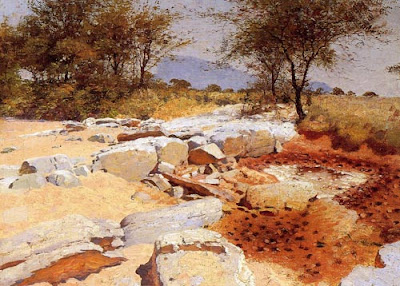

Leigh did brilliant studies in Africa (above) as preparation for his diorama paintings. But great as he was as a painter, some of his backdrops were criticized for their distracting style. Trained in Germany in the Dusseldorf tradition, he had a hard time getting rid of the very theatrical lighting, brushwork, and unnatural colors that served him well as an easel painter. The backdrop below is by W.R. Leigh.

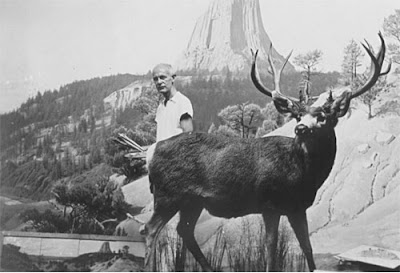

The person who fit into the role perfectly was James Perry Wilson, who I’ve mentioned a few times before in other contexts. Wilson came from a background in architectural illustration, and was largely self-taught. He first worked at the museum assisting Leigh, who was 20 years older. Wilson learned the craft, and then applied his own intellect to the unique challenges of the art form.

Wilson (above) was a slow painter and a bit aloof in his personality. The detailed story of what he went through to navigate the museum politics is told in the latest chapter of Wilson’s life by online biography.

This chapter is no ordinary blog post. Wilson’s story is being written by the Peabody Museum’s own Michael Anderson, who originally planned it for a book, but is publishing it online instead, chapter by chapter.

---------

Wilson Biography, Chapter 5: Joining the American Museum of Natural History (scroll halfway down for the discussion of stylelessness).

Quote is from W. R. Leigh, Frontiers of Enchantment. 1939, p.49.

The big book on the AMNH diorama is Windows on Nature by Stephen Quinn

Previously on GJ: "James Perry Wilson's Dioramas"

17 comments:

Thanks for the heads-up on the latest chapter in JPW's life. In my childhood (early and mid 1950's) I had the privilege of making several pilgrimages to the AMNH. Though I wouldn't learn their names until years later, I was mesmerized by the work of Wilson and another painter, Francis Lee Jacques. I had no concept of "stylelessness," but I certainly responded to the power of these painted backdrops to create depth, space, and light. I do remember a feeling of sliding in and out of the awareness that what I was looking at was "simply" paint.

This work reminds me quite a bit of what matte painters do for the film industry. I read somewhere that if you see a matte painting on film, typically it can only be shown for a few mere seconds before the eye becomes aware of the illusion. There are a few great examples in the book: "From Star Wars to Indiana Jones: The Best of the Lucasfilm Archives"

Do you ever paint on glass?

Correcting a spelling error in my earlier comment; it's Jaques, not Jacques.

"Sliding in and out of the awareness that what I was looking at was "simply" paint." That describes the experience perfectly, Steve. It also reminds me of the experience of watching the first 3-D big-screen Imax nature films. You forget you're looking at a screen.

Dan, yes, I'm glad you mentioned matte painters in film, whose work has to blend with the particular look of the lens and film stock, the other matte painters, and the directors vision--all so that you don't stop and say, "Hey, a matte painting!"

Another good book on their work is "The Invisible Art."

James,

did you approach your backgrounds in this manner for Fire and Ice or did you have a certain level of creative freedom? Obviously the environments didn't exist, but were you given strict protocol?

I just watched that again the other day and some of those paintings were astonishing, especially given the tight deadlines you and the team must have been on.

-Kelly

Great to see this post! The diorama painting at the AMNH have fascinated me since childhood. Nice to be able to put some names to the work.

anyone interested in the AMNH windows, I highly highly HIGHLY recommend "windows of nature"

http://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/dioramas/book.php

I have NEVER known anyone who looked at this book and was not amazed. It's a fascinating story about how the windows were made.

EXCELLENT! Thanks!

When I lived in NYC and got to venture to the AMNH, I swear I spent far more time staring at the backgrounds than the actual taxidermy. There's some fantastic blending of the seams too - where the ground planes and physical landscaping meet the wall. They are quite a treasure to experience in themselves.

Your views on not having a style make me wonder if Impressionist landscape painters like Paul Cezanne or Claude Monet would have made it as backdrop painters themselves.

@ max,

Funny you should say that because the painter of the background for the moose diarama at the AMNH (his name escapes me) did just that, and i don't think it is nearly as effective as the other paintings.

there is some debate whether he ever finished it.

My Pen: I wonder if you mean Carl Rungius. He was a great wildlife painter, with very vigorous impressionist handling. But his moose backdrop doesn't really work as an illusionistic painting.

Max, I think the same thing would happen if Monet or Cezanne tried backdrops. Their paint strokes and their style would stick to the wall and kill the effect.

All of which raises a whole set of aesthetic questions: why do we bring different expectations to a framed painting in a gallery or a museum compared to the expectations we bring to a backdrop illusion? Should the painterly surface make an appeal to the eye apart from the paint's role in illusion-making?

I think this question has been answered differently by artists at different times in history. In Asher Durand's day, the scale was definitely tilted more in favor of illusionistic painting.

I always loved going to the museum of natural history in San Francisco as a kid and looking at the diorama backgrounds. As much as they were style-less you could still tell the different artists from one another if you looked. I guess not having a style doesn't stop you from being unique.

"Windows on Nature" was written by a colleague of mine, Stephen Quinn, who has spent his career at AMNH.

In November, as a recipient of a Artists for Conservation Flag Expedition grant (I was awarded one last year; it's a great program!), he traveled to Rwanda to search out the exact spot which inspired Carl Akeley's gorilla diorama at the AMNH.

If you are interested you can find out more, and read the expedition blogs, here: http://artistsforconservation.org/programs/flag-expeditions/expedition/11/how-artist-saved-mountain-gorilla

Neat! I love it when museums obviously take the time to get quality art in.

Most recently, I think I was struck by the mural for the Lucy's Legacy exhibit when I saw it in Seattle. Apparently it was done by artist, Viktor Deak, and you can see panels from the mural here:

http://www.anatomicalorigins.com/www.anatomicalorigins.com/2-D_Digital.html

You can see his workspace here:

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2009/06/02/science/20090602-prof-pano.html

@ Steve: Thank you for mentioning Francis Lee Jaques.

He is my husband's great-uncle, and many of his works are still in the family. Besides being in the National History Museum in NYC, he did a lot of diorama work in museums in Minnesota, where he and his wife lived for many years. Though he died twenty years before I joined the family, I have enjoyed many stories of him over the years. They called him 'Lee.'

Post a Comment